The Partners of Greenwich Village

It’s been over 15 years since I married. For most of those years, I spoke of being a husband, of having a wife. That changed when the person who I married—and to whom I remain married—began what we did not then realize was a process that would end with him coming out as transgender. Gendered pronouns were to change, but first we wrestled with the language of relationship. We tried on “spouse” for a while—as in, “my spouse taught our son to climb trees,” (which is true). I felt awkward in the usage at first—it isn’t common—but eventually got used to it and even liked it. My spouse never did. We tossed around “partner,” but wasn’t that too businesslike? (Or maybe too queer for how we then made sense, or tried to, of ourselves.) But since spouse did not catch on, and “lover” only worked for a laugh, we landed on “partner” after all. I thought we were being very modern, that this was a new sort of relationship. Then a census-related query from historian Ansley Erickson proved me very wrong.

Erickson had run across the “partner” label in the 1940 census and asked if I knew anything about its usage. (The specific fascinating case is Erickson’s story to tell.) As for me, I had never noticed any “partners” before. (Not that I was looking.)

The instructions to census takers were no help. They mentioned servants and lodgers, but not partners. Here’s what they said:

A household, as the term is used for census purposes, is a family or any other group of persons living together, with common housekeeping arrangements, in the same living quarters. Although ordinarily a household will consist of a head, his wife, and their children, the persons in a household may or may not be related by blood or marriage. Include a servant, hired hand, or other employee who sleeps in the house as a member of the household for which he or she works. Consider a boarder or lodgers a member of the household with which he lodges, if that is his usual place of residence. (page 37, paragraph 420)

Bureau officials in 1940 assumed a male head of household. I’ve seen some exceptions, where a wife gets noted down as head and her husband as spouse. The possibility stirred up men’s insecurities—at least that’s what I take from this 1930 political cartoon:

Reading a bit further, I learned something else of interest. The key to householding (for census takers) was not sex, but cooking. It didn’t matter so much who slept with whom, but rather who shared a stove.

If a married son or daughter or any other person lives in a separate portion of the house that has its own cooking or housekeeping facilities, such persons constitute a household separate… (37, para 421)

If I did find any more partners in census records, the most I could say with certainty was: they probably used the same sink.^

[Update: While the handbook for enumerators said nothing of partners, the “Instructions for Filling Out the Population Schedule” did: “If two or more persons not related by blood or by marriage share a common abode as partners, write head for one and partner for the other or others.” Partner was an official category. Update II, from the annals of keep reading the handbook, dear researcher: the enumerator instructions do eventually include the same sentence as above, on page 43, paragraph 451: “If two or more persons who are not related by blood or marriage share a common dwelling unit as partners, wright head for one and partner for the other or others.”]

Turning to statistics from the census, I learned that there were in fact, 200,152 partners in the entire census ledgers. That’s a number of orders of magnitude greater than “concubine/mistress and children” (105) and about on par with cousins (151,487). But it was less than one percent (0.74%) of the number of spouses (effectively “wives”).

Less than one percent of the number of spouses! This did not bode all that well for my quest to discover some more moments when a census taker scribbled “partner” in the bureau-issued portfolio.

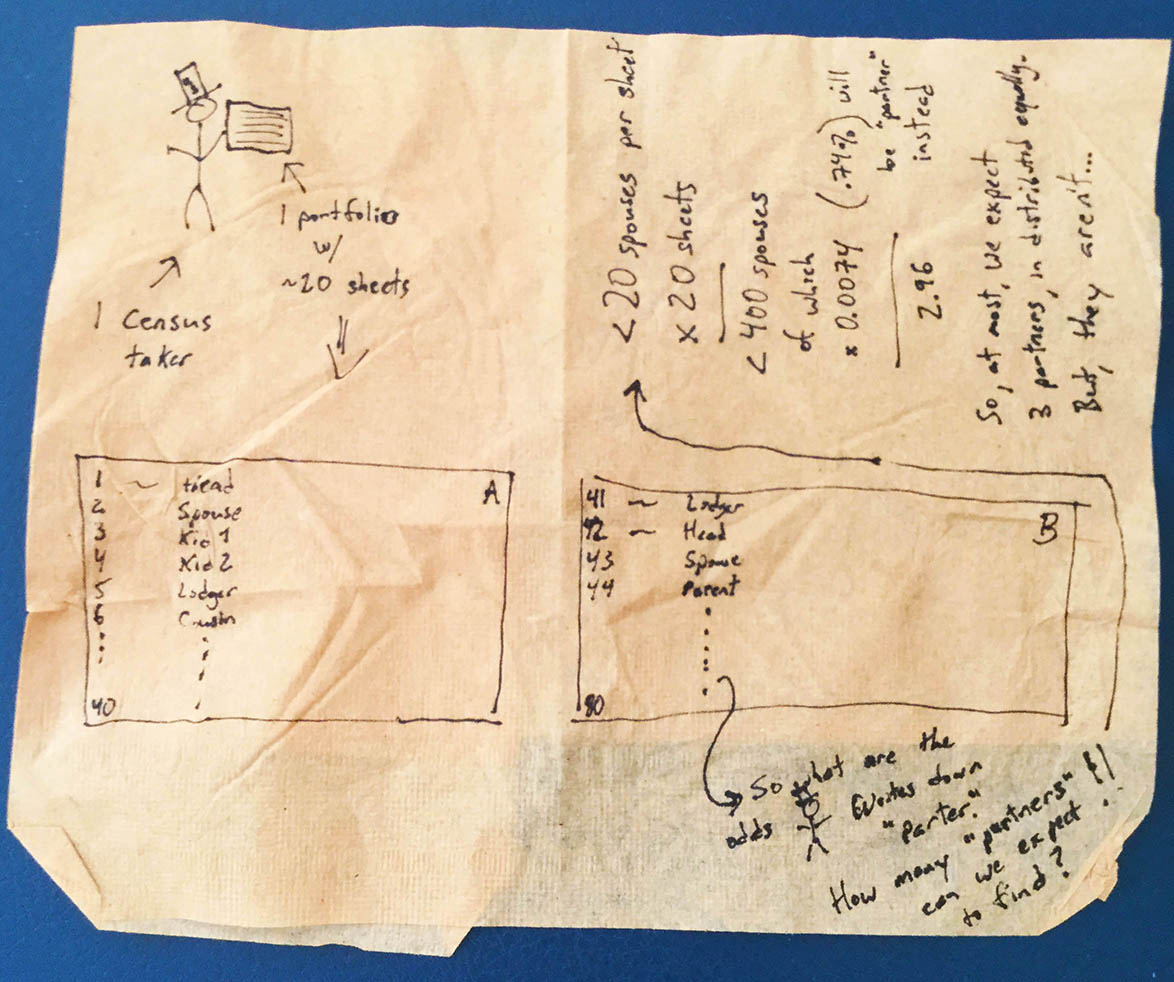

Let’s do some back of the napkin calculating: (explained after the image, in a manner you might actually be able to read…)

Each enumerator carries a leather government-issued portfolio, from which they fill out something in the neighborhood of 20 enumeration sheets. Each two-sided sheet fits 80 names. Most people on the schedule will be heads of household or children, and when we also factor in lodgers and other relatives, spouses end up appearing less than once ever 4 names on a sheet (on average!)

So! We’d^^ expect fewer than 20 spouses on each sheet. That means we’d expect fewer than 400 spouses per enumerator. And so, ta da: we’d expect (400*0.0074=2.96) fewer than three partners per enumerator, if every neighborhood was just as likely as any other to be home to partners.

My hunch was: partners would show up more in some places than others, a hunch premised on my prior experience. I had never noticed a “partner” before.

Where? Well, I took a potentially anachronistic gamble and guessed that partners would be more likely to turn up in queer communities.

To begin, I turned to what historian George Chauncey has written was considered New York City’s “most infamous gay neighborhood by outsiders”: Greenwich Village. (227)

Lillian Rita Davis took the census on the block that tracked West 11th Street to West 4th to Perry Street to Bleeker Street. In that little block, her enumeration district (ED) 879, Davis recorded 12 partners. Remember, we expected to find 3 at most. My hunch started looking pretty sound.

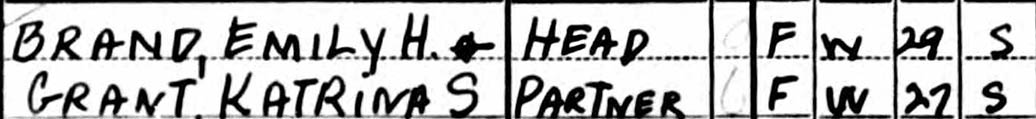

The very first door that Davis knocked on belonged to two women, both college graduates, originally from Michigan, in their late twenties. Emily Brand worked as a secretary in a theatre company, earning $429 over the course of the year for it. Money must not have determined who got to be labeled “head”, since Davis gave Brand that distinction, even though her “partner” Katrina Grant earned $1,330 as a social worker.

All we can say for sure about Brand and Grant—and the other 11 partnerships that Davis recorded—is that they shared a sink. It seems likely that at least some of these households did live together as lesbian or gay couples. But it could also be that we find so many partnerships in this gay neighborhood, because the presence of queer folk indicated or amplified social and cultural spaces in which people could live openly in odd (that is, unusual), but non-sexual arrangements. The census didn’t ask about sexual identity or sexual behavior, and so we cannot know from the census alone.

As for those other partnerships, five partners were women living with another woman, the pairs always within a few years in age. They included a pair of doctors, two travel agents (who may have been business partners, if nothing else), an editor and a secretary, and a secretary and a stenographer who both worked for the YMCA(!). Two of the partners were male-male, including a police detective who lived with a patrolman.

The others are more difficult to parse. There’s a cooper (who made liquor barrels) marked as a partner, either to a woman who did insurance accounting or to her brother, an apprenticed electrician. There’s a 27-year-old subway track walker, born in Italy, marked as partner, but in whose household I cannot say. Certainly the most intriguing and confusing, is the case of a renowned, divorced psychiatrist, Viola Bernard, marked down as “partner” in the household of a domestic court judge and her husband, a National Labor Relations Board lawyer, along with their two children. “Partner” helped Davis transform this peculiar (and fascinating) living arrangement into something the census could comprehend.

But Lillian Davis’s days of wrestling murky reality into state-approved statistical buckets came to a sudden end when she got a new job (“found employment in private industry” according to a note on one of the sheets) and left the census.

Davis’s adventures in enumerating made a good case for—at the very least—linking “partners” to gay and lesbian neighborhoods.

Patrena Greco’s census schedules make me more confident that Davis’ block wasn’t a fluke. Looking back to Chauncey’s Gay New York, I read:

A middle-class gay residential enclave developed on the Upper East Side in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. Many gay men moved into the railroad flats in the East Fifties and Sixties east of the Third Avenue elevated train, which allowed them to live close to the elegance of Park Avenue (as well as the gay bars of Third Avenue) at a fraction of the cost. (159)

Enumeration district 1272 lay smack in the middle of that developing gay enclave. That’s where Greco went counting, and that’s where Greco recorded 13 partners—quite a few more than the 3 we^^ expected. But the census stories of the partners of the Upper East Side, will have to wait for another time…

^The folks at the Minnesota Population Center, who maintain the invaluable Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS), explain: “Before 1960, the category ‘partner’ refers to a non-relative who shares the home and expenses with the head, including responses such as co-head and business partner.”

^^Those who are grammar aware, may note here that I’ve switched out of the first person. I’m employing instead the statistical ‘we,’ a we that abides in a world where it’s possible to have 2.5 kids.