Why A Census Matters

Why does the census matter? A few answers appear often in recent reporting and opinion pieces worrying that the Trump administration may be sabotaging the 2020 census, by underfunding, inadequate staffing, and questions about citizenship that could deter participation. A lot is at stake, such writing correctly reveals: the distribution of $600 billion in federal funds depends on census counts, as does the allocation of representatives among the States. (Recall: the Constitution created the census count in order to fairly apportion representatives and levy direct taxes). Business too depends on census figures, especially the ‘research industry’ which makes money by gathering, repackaging, analyzing, and selling free government data. We need not be surprised that political writers emphasize the (immense) political significance of the census. To them, the census is about wealth and power.

There are, though, other reasons the census has been understood to matter (as I’m sure these writers would agree). Those reasons come from seeing the census in a very different light, as a source of meaning (and stories!). What I am saying is: the census is even more important than you thought.

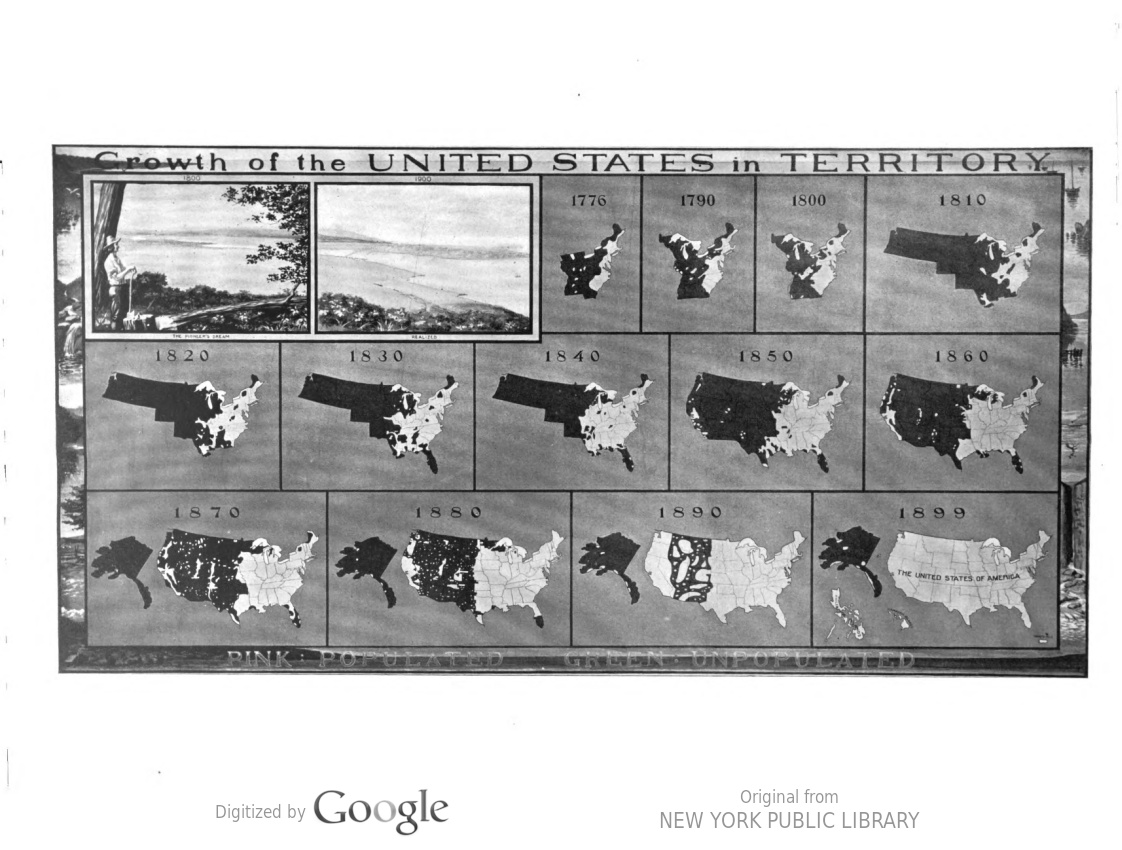

The census plays a key role in crafting the nation’s identity and, for much of its existence, it provided a basis for tracking the United States’ progress. The fascination with progress found its most common and powerful form in the idea of the “frontier.” Census data allowed mapmakers to paint a retreating wilderness (in the process erasing Native Americans and others who lived in these supposed voids). The Mutual Life of New York prepared one such frontier image for the Paris Exposition of 1900—note how the image casts the American nation as a white, male pioneer clearing the woods and how it celebrates America’s imperial arrival after the 1898 conquests of Hawai’i, Cuba, and the Philippines.

Even after the frontier had been declared closed, census officials saw themselves as gathering data that would illustrate just how exceptionally blessed America was. Consider this poem (another one!) written by a Memphis district supervisor for the 1930 census to inspire his enumerators and encourage public cooperation with them. He wrote, near the beginning:

To get the facts on which to boast that U.S.A. folks have the most

Of life’s good things by which they thrive and are the happiest alive.

Enumerators by the score will soon be passing door to door

To get those facts which must be had to make our Uncle Sam feel glad.

He closed his verse:

Uncle Sam is asking, and he wants to know,

How his sons and daughters are progressing, fast or slow.

As that last line suggests, the census did not merely celebrate: the census provided data to highlight problems and possibilities. In the antebellum years, it fueled arguments between pro-slavery intellectuals and abolitionists. One of the earliest and most significant of such fights began, according to historian Patricia Cline Cohen, with the 1840 census when faulty forms led to the mistaken conclusion that free African Americans suffered from insanity to an astounding degree, while mental illness left enslaved people undisturbed. (This wasn’t true.)

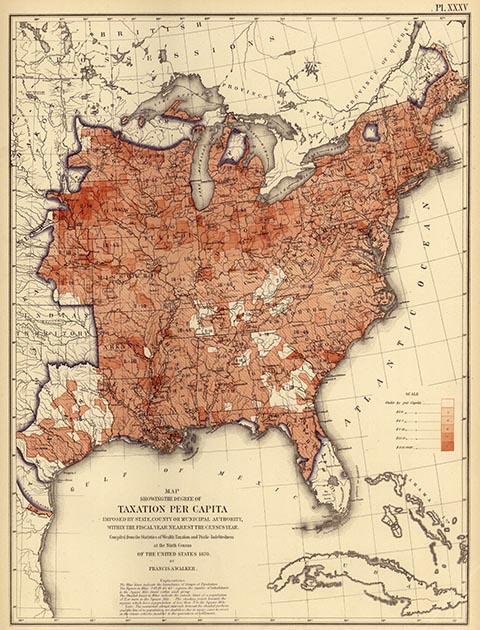

After the Civil War, the statistician Francis Amasa Walker pioneered graphical techniques that turned census figures into data ripe for mining. In Susan Schulten’s words, Walker “invented the American infographic.” His beautiful maps and charts presented the nation from a variety of angles, at a glance. But by graphing multiple variables together, he also created a tool to look for relationships, for possible effects and their causes. Below, Walker displays tax per capita figures arranged geographically and overlayed with information about population density.

Find more of the maps gathered helpfully here, by historian and cartographer Bill Rankin .

The census started out as a political tool and continues to have that purpose, but as it has grown and expanded in scope it came to see itself—and be seen by others today—as the single most important source of modern facts about the United States. A film announcing the coming 1940 census put the point quite forcibly, saying that the census provides: “unbiased facts to measure markets for business and the farmer, plans of school and health officials, the needs of local governments, facts to guide the lawmakers, facts from which a free people can count its gains and chart its future.” The census depended on citizens to make themselves known and offered to reveal the state of the nation in return:”for: You cannot know your country, unless your country knows you.”

There’s another reason the census matters to ordinary people these days, one that’s frequently overlooked: genealogy. Whenever I visit the National Archives or Library of Congress I am surrounded by genealogists plumbing their familial pasts. Americans today aren’t just using the census to know their nation. In fact, I’d wager that many more people now turn to the census to know their families. But that’s a big enough topic to warrant another post.

I’ll just close with this note: the people organizing the 1940 census could not imagine today’s flood of genealogical researchers. In a press release from the mid-1930s, a senior census official bragged that 3,608 people managed to secure permissions to dig through census archives in a year (for a variety of reasons: to prove eligibility for a Civil War pension, to fight over an estate, to get a work permit, to apply for old age pensions, and to construct genealogies). Although I haven’t found any firm figures yet, I wouldn’t be surprised if that many people logon to Ancestry.com to search census records every hour. Mid-century Census officials did understand why many people now turn to the census: “Every person in the United States, however insignificant he may be, has a permanent place in the history of the country, for a record of his personal life is made by the National Government every ten years and filed away in the government archives. Nobody need feel that he merely lives and dies without the facts about this existence permanently recorded, Census officials have pointed out.” The census records and valorizes each individual and preserves them for posterity. The public was waiting: “No indication has yet been made as to when the 1880 records will be thrown open, but genealogists and historians are eagerly awaiting that event.”