A Predictable Population

What does each census mean? What story does it tell? For Stuart Chase, the census of 1940 proved that America had become, if not boring, then at least predictable.

If the 1930s had a Tom Friedman, it was probably Stuart Chase: a well-connected journalist, a smart, zippy writer, a shrewd troubadour of the politically and economically trendy. Chase called into being an emerging “New Deal” (in a book by that name, appealing for aggressive regulation and reformation of the economic system) that came to seem as real and inescapable as Friedman’s idea that “the world is flat.” As he did in so much of his writings, Chase busied himself in a 1941 pamphlet What the New Census Means teaching Americans to think in a very new way about their country.

Chase claimed that the census of 1940 staged a “statistical drama,” even a “statistical miracle.” (This despite his own assertion that usually “Statistics is one of the least dramatic of sciences.”)

The drama played out in the count itself:

“The Census enumerators counted us, in our homes or off on vacation or in hospital or in jail, and they did not count us twice…more than 35 million interviews—–within a few weeks. They fed the interviews into the hoppers of their computing machines, and the machines have been grinding away ever since, dropping out totals and subtotals from time to time.” (1-2)

But the greater drama, indeed the miracle, revealed itself to Chase in what the census count confirmed: America’s population could be accurately predicted by expert forecasters.

Chase wrote:

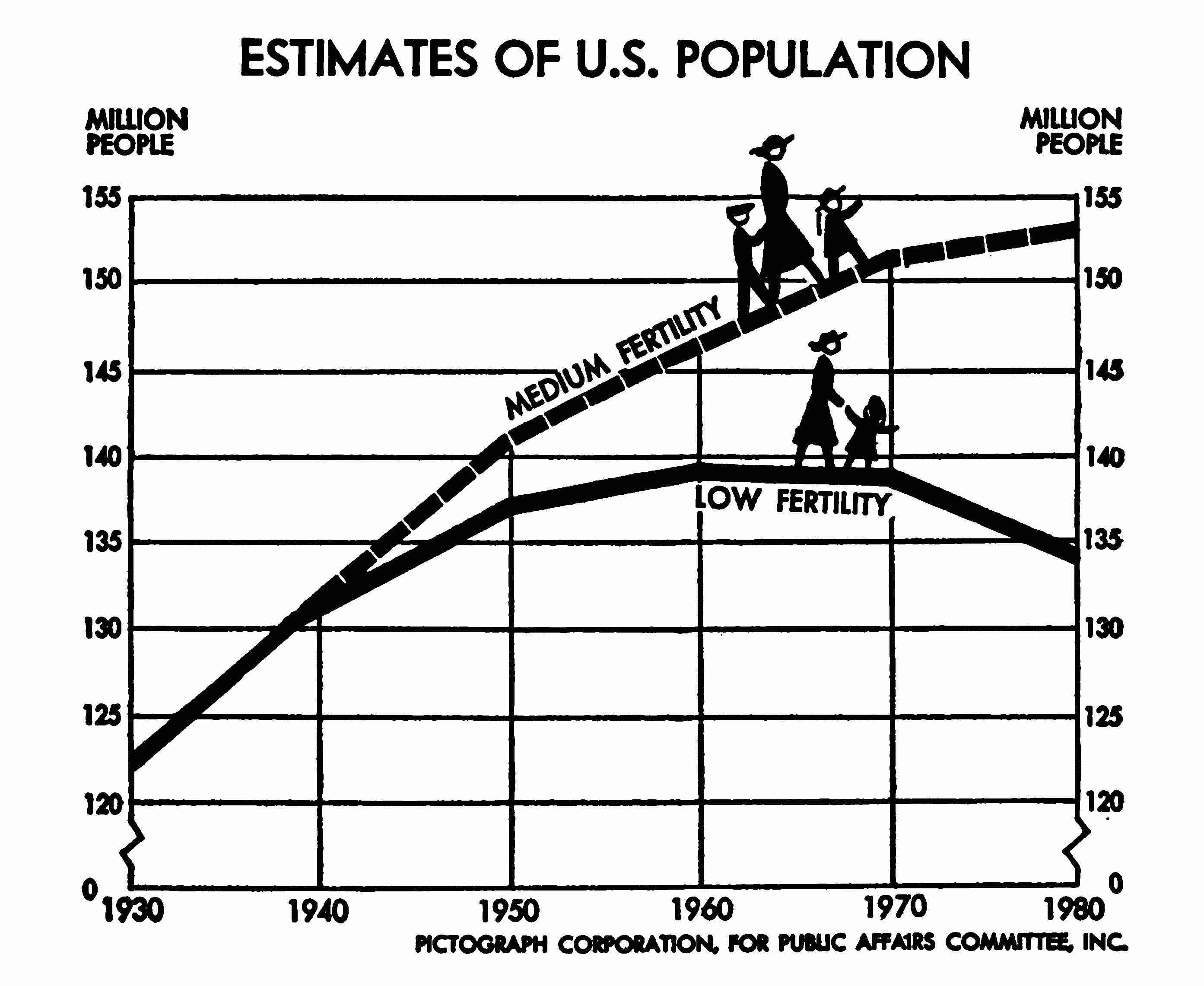

“Four years ago the experts had made varying estimates of the 1940 population, based on different sets of possible circumstances, as to birth rate, death rate, and immigration. Of these estimates they chose the two most probable—about 700,000 apart. That is, they gave themselves the leeway of a little more than half of 1 per cent of 131 millions. In the middle of this leeway, splitting the difference between the statisticians’ two favorite estimates, lies the figure 131,650,000. Out of the Census Bureau hoppers came the figure 131,669,275….They hit the bull’s-eye.”

You can’t even make out the space for the bull’s-eye in the accompanying pictograph:

But the census hit it, nonetheless.

To be sure, Chase’s miracle depended on his own strained reasoning. The population researchers Pascal K. Whelpton and Warren S. Thompson, who had made these predictions, never intended anyone to take the average of their low and medium fertility projections. There was no bulls-eye to hit. It was no so much that the census proved the projectors right as that it suggested that fertility in the US was somewhere between the low and medium levels.

At this point in Chase’s story, the census exited stage left. Having celebrated the population researchers’ short term prognostications, Chase embraced their big idea: that the United States was nearly done growing. The nation had, as Chase and others put it, reached “maturity” (more on that in the next post).

Prediction struck more people than just Chase as potentially miraculous as it became not just political, but electoral in the 1930s. George Gallup, Elmo Roper, and Archibald Crossley each, separately, embarrassed a famous Literary Digest survey and many hopeful Republicans in 1936 when their scientifically sampled polls predicte that sitting president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, would prevail in his bid for reelection against Alf Landon. Election polls joined a parade of existing official predictive practices, some dating back millennia (like astrology), some bearing a distinctly nineteenth-century flavor (like crop reporting), and others distinctly new fangled (most notably business or price projections and indices). Soon enough, Gallup and Roper’s polls led the parade. How did Americans come to believe in polls (or why did they doubt them) and how did polls help forge the idea of a coherent American public? You can find the answers in Sarah Igo’s masterful and delightful The Averaged American.

But while many, many political commentators or American historians could tell you that 1936 marked a turning point in polling, far fewer pay similar attention to 1937’s (in their own way) equally influential population predictions.