The Muralist and Enumerator

The records of the U.S. Census Bureau reside in Washington, D.C., in the National Archives building built in the depths of the Great Depression to provide a monumental home to federal records. Inside those acres of white marble visitors encountered the founding of the United States in murals and on parchment. Instead of “Washington Crossing the Delaware,” a martial celebration of the nation’s birth through grit and force, the exhibition hall presented a nation made on paper. While tourists today still line up on the Constitution Avenue steps to pay respects to the Bill of Rights or Declaration of Independence, genealogists and other researchers like me breeze through the Pennsylvania Ave entrance and (after some card swiping and paper shuffling) take our seats at grand wooden desks in a well-lit, stately reading room. Researchers call the facility, affectionately, NARA-1, distinguishing it from the much larger, but less grand -National Archives facility in College Park, MD.

From my favorite desk, I can peek out the windows and see the facade of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. (I suspect you heard about a couple portraits recently unveiled there.) When the day ends and I climb out from under the records I’ve requested—neck creaking and lower back aching from leaning, reaching, typing, photographing—I often walk a few blocks north to wander among the canvases.

I have a favorite:

Like many of the paintings I love, “Subway” teaches the viewer to see something special and valuable in the mundane. It’s a mildly subversive piece: We’re being invited to stare at people on the subway! Meanwhile, the subjects of the painting must stick to approved subway behaviors: furtive glances, quiet moments with friends or lovers, and above all the sustained performance of inattention to one’s neighbors.

“Subway” also wants to teach how to better see the USA. It presents an integrated whole and treats this crowd with the dignity afforded white, native-born men at the time. The painting’s central subjects are, to my eye, from left to right, a young woman applying lipstick, a dapper African American man who wears cool socks, a musician who for some reason I think is meant to be an immigrant from southern or eastern Europe^, a worker in a blue shirt (possibly Japanese), and a white woman in a compelling two-toned green dress. Lily Furedi instructs us in seeing the nation represented by an A train car.

(^in support of that hunch: according to Wikipedia, Furedi’s Hungarian father was a cellist…)

Born in Budapest in 1896, Furedi lived in uptown Manhattan, far uptown, past Harlem, in Washington Heights at 719 West 180th near the just-opened George Washington Bridge (and near the coffee shop where I’m composing this post). She painted “Subway” in 1934 as part of the “Public Works of Art Project,” a federally funded relief program for artists that employed 2,500 artists and sponsored over 15,000 works of art in just one year—it was a cousin to the more famous Federal Writer’s Project of the WPA (Works Progress Administration) that employed soon-to-be luminaries like Zora Neale Hurston and Richard Wright. They were hired to prepare an extensive series of guides to American places. Like Furedi’s painting, they too evidenced a commitment to providing an alternative to nativist and racist nationalisms that had just a decade before inspired immigration restriction and allowed the Ku Klux Klan a seat in the inner circles of the Democratic Party.

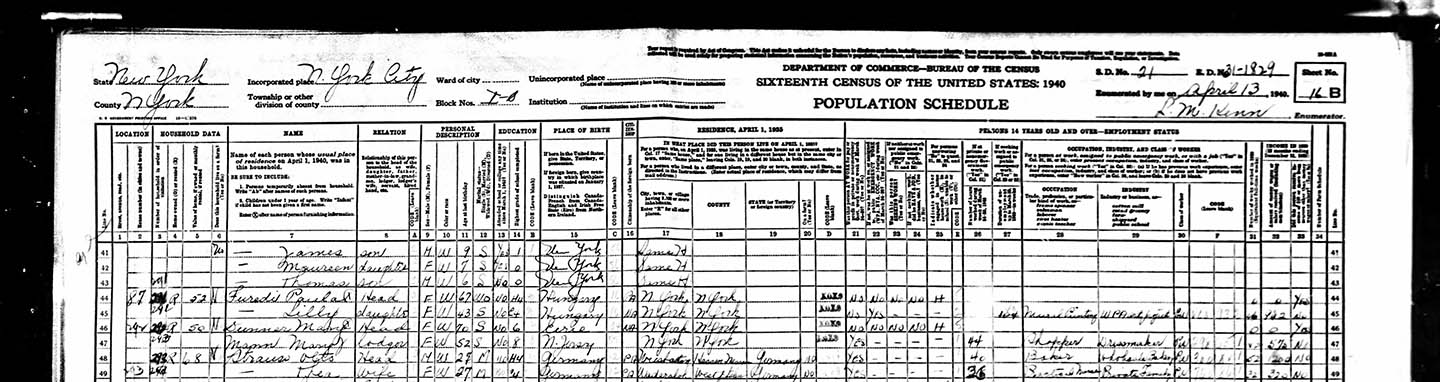

Furedi became the subject of a very different sort of project to depict America on 13 April 1940, when Lucile M. Kenn knocked on the door of Furedi’s apartment. Paula Furedi, Lily’s mother, probably invited Kenn in and asked her to take a seat. Kenn drew out a large leather portfolio containing her census forms. On side B of sheet 16, Kenn recorded the summary details of the two Furedis’s lives.

By 1940, Paula and Lily (Kenn misspelled it “Lilly”) had moved to Harlem where they paid $52 a month for an apartment in a building at 87 Hamilton Place. Kenn distilled Lily Furedi down to her census-defined categories: female, white, single, 4-years college educated, a naturalized citizen born in Hungary, and—as her occupation— “mural painting.” Furedi still received federal artistic support, now through the WPA art project and may well have been off working at the very moment of this interview on a set of murals to be displayed in Bellevue Hospital’s psychiatric building. Furedi’s “Simple Way of Life” mural appears aimed at transporting patients and staff out of New York City and into an idealized rural town. (I have yet to determine if these murals are still hanging somewhere in Bellevue…)

So far as I can tell, the census taker, Kenn, does not herself appear in the 1940 census. Her husband does and his record reveals a family that had fallen on very hard times. It was not until 24 April 1940 that a census taker named Sagwill W. Hackman found Norman J. Kenn in a boarding house at 2683 Briggs Avenue in the Bronx. Norman Kenn listed private chauffeur as his occupation, but it was an occupation that had little occupied him of late. The Depression left Norman unemployed for that last 80 weeks. The precise method by which enumerators were selected and hired are hard to uncover, but I wonder if Lucile Kenn’s hard-up husband gave her an advantage. It certainly gave her a reason to seek the month of work for Uncle Sam.

Very little links Kenn and Furedi. I have no reason to believe they even met, since Paula Furedi answered the census questions. Yet their lives in New York City ran in parallel: they were born within a year of one another and died within months in 1969. And for at least one month in 1940 they shared a patron and a purpose. Both worked for the federal government—alongside the architects and builders who had just finished the National Archives building, and the writers who in 1939 finished the guide to New York City—as participants to the grand project of displaying and explaining America to itself.