When the U.S. Counted Puerto Ricans for the First Time

The United States invaded Puerto Rico in July 1898. A little more than a year later—in September 1899, President McKinley ordered a census of this new colony (ceded by Spain along with Cuba, Hawai’i, and the Philippines). The task did not fall to the Census Bureau, but instead to the War Department, which issued its final report in November 1900.

I decided to start digging into the history of the US census in Puerto Rico as my first (very small) contribution to the protests now drawing attention to the thousands of deaths unaccounted for in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. (A recent estimate based on a random sample census places the death toll at 4645, orders of magnitude higher than the official figure of 64.) A rally outside the UN on Saturday, June 2 called for an “audit” of death records to go along with the existing move to audit Puerto Rico’s debt (and the Poor People’s Campaign’s parallel audit of American poverty) In her message on Sunday, my pastor—Rev. Dr. Damaris Whittaker—invited us to stand together under a tarp meant to further remind us of Americans in Puerto Rico still without homes or electricity—and then to ponder the compounding tragedy that comes with our continued ignorance concerning the victims of the hurricane and its aftermath.

Given the gravity of this moment, I feel like I need to apologize up front: what follows is only the beginning, just the barest bones of a story that demands to be fleshed out further. (And no doubt has been by scholars whose work I am right now seeking out. Suggestions welcome!)

Before the US constitution imposed a decennial census on all citizens, counting people often came in the context of colonial rule. In her pioneering work A Calculating People: The Spread of Numeracy in Early America, Patricia Cline Cohen tracked the earliest North American head counts to 1620s Virginia, where opponents of the colonial project hoped to expose how many migrants from Europe had died already. For the most part, though, she points to censuses instigated by advocates of empire or colonial bureaucrats who were working to exert control of trade and taxation in faraway lands. Cohen points to censuses in the 1660s and 1670s in the sugar-producing, plantation-laden island of Jamaica, followed after 1696 by a flurry of counts in Bermuda, Maryland, Newfoundland, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Virginia. Pennsylvania, a more independent colony, notably avoided a census at this point.

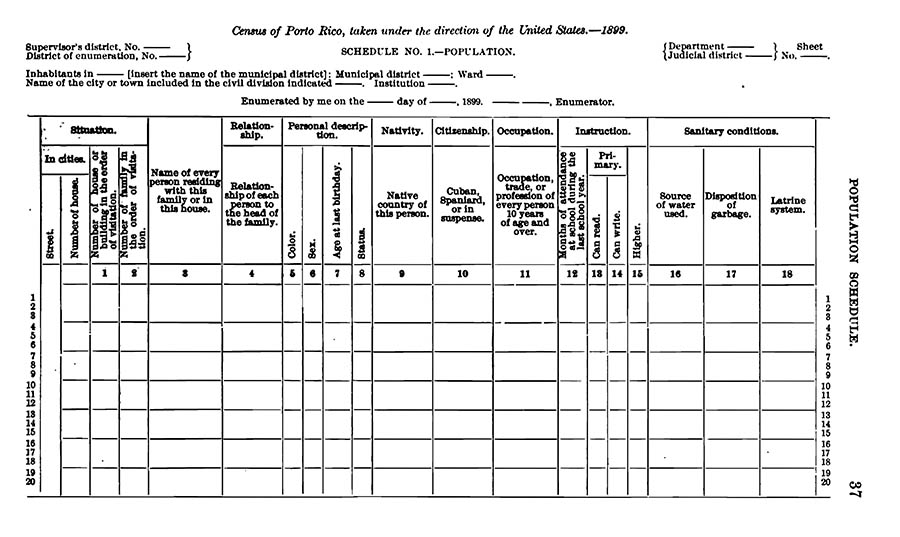

Given that history, the first Puerto Rican census signaled a return for the practice of head-counting in America—back to empire. The War Department enlisted Puerto Ricans to count themselves—returning a total of 953,243 (about the size of West Virginia, the report noted on 40). Herman Hollerith and his Tabulating Machine Company–the forerunner to IBM–processed the results, as the company had just done to much acclaim for the 1890 census. Hollerith’s “accurate and expeditious” (38) system of electronic sorting and counting devices tallied findings on paper cards derived from answers to this set of population questions:

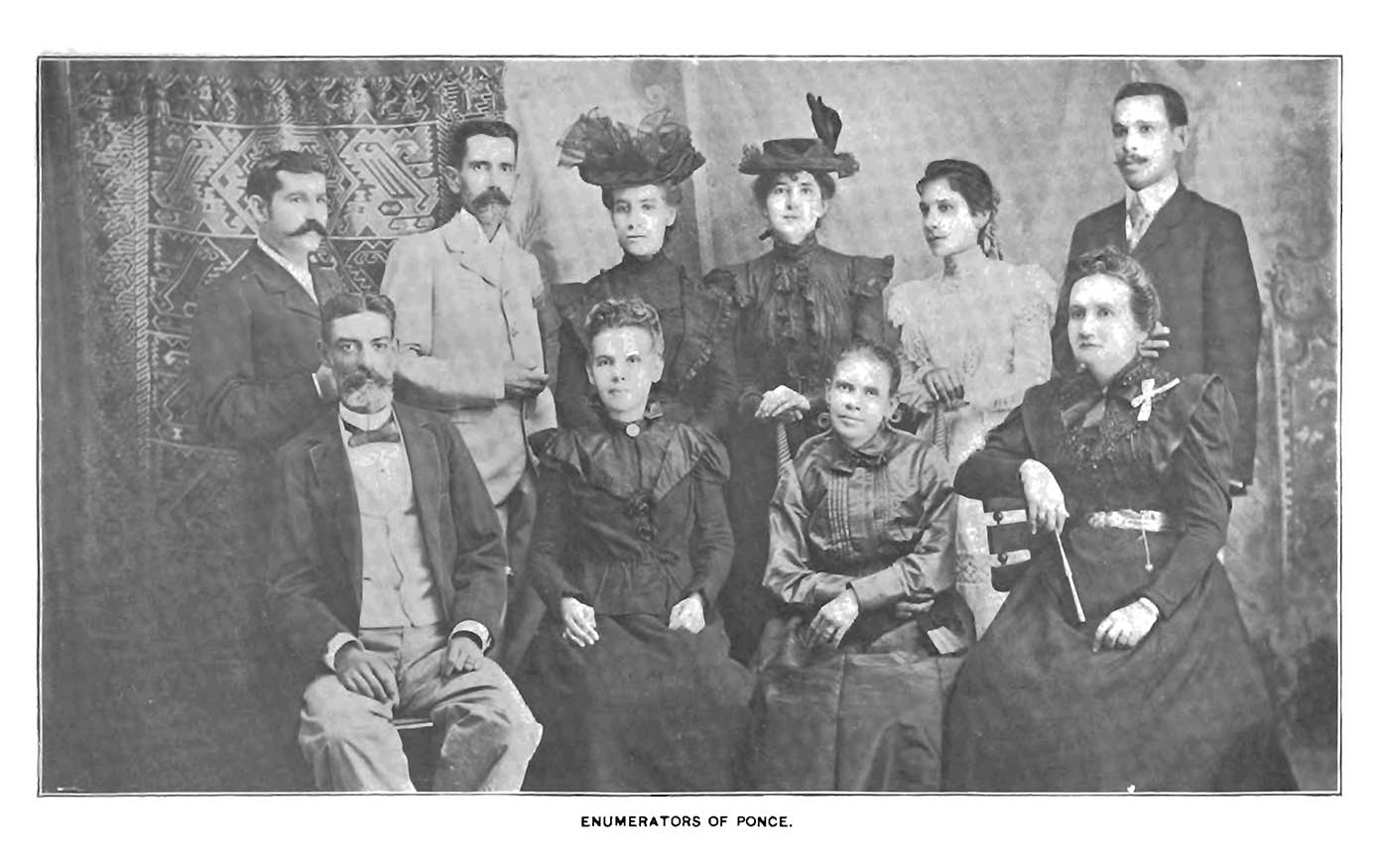

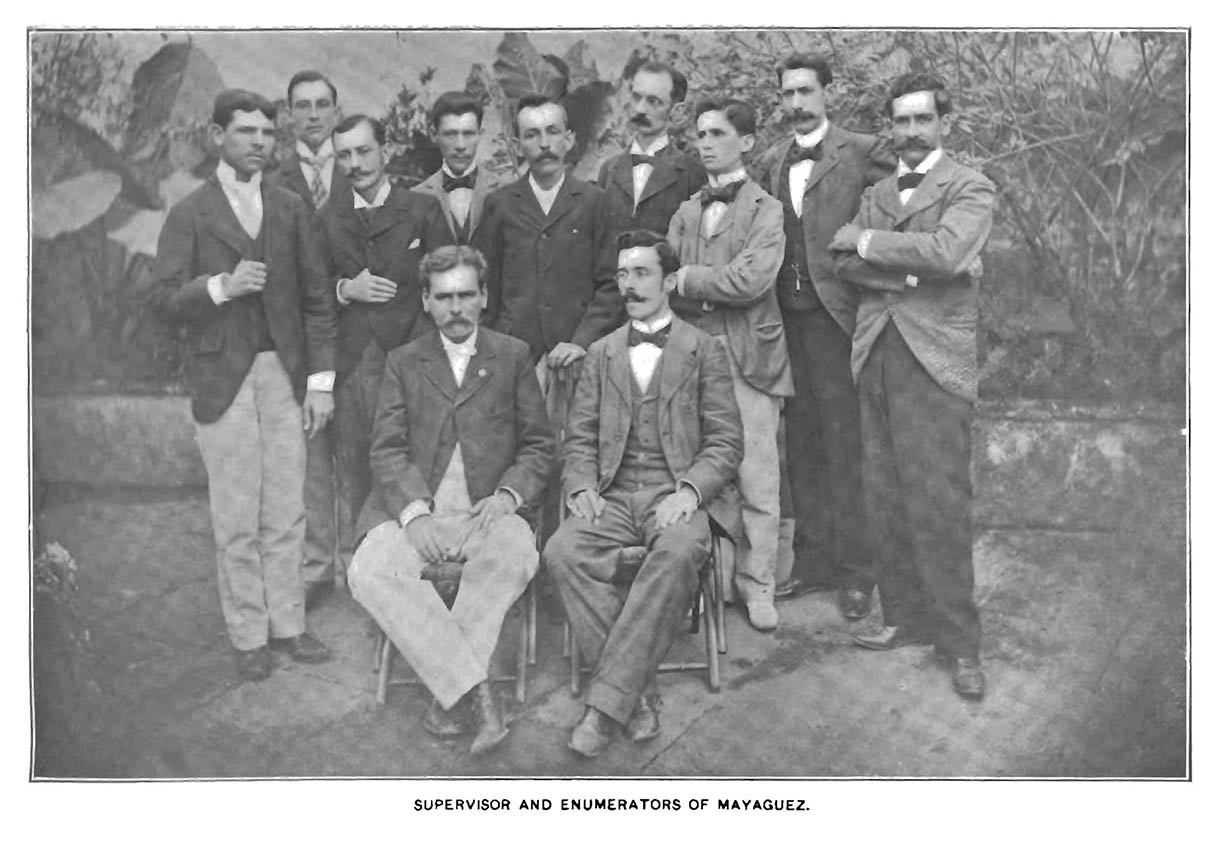

Decennial census takers disappear from the final reports and official announcements. The War Department’s crew of enumerators, in contrast, were put on display.

The report sketched out a portrait of Puerto Rico. Illustrated by photographs of landscapes, homes, people, and even romantic ruins, the report surveyed the history of the island (at least its history since European conquest), talked about its climate and geography, and discussed in depth its sources of past and future wealth (with very long sections on coffee, sugar, and tobacco production). Still, questions of population dominated, and among those questions the most energy went into organizing Puerto Ricans by a variety of categories of race. (A big topic I’ll return to in a future post.)

If there was a single story pervading the census, it was this: Puerto Rico could be readily ruled and The U.S. had been and would be generally embraced:

At all events, the troops of the American Army received from all classes of natives in all parts of the island occupied by them a spontaneous and enthusiastic welcome as deliverers and friends. (19)

I suppose that was the reason to photograph the enumerators, in blouses and bow-ties too—to show that they could and would cooperate.

How might we interpret the work of these census takers? In a 1990 article in American Studies, the scholar Clara E. Rodriguez shed light on why some prominent Puerto Ricans did indeed welcome and support the U.S. invasion: “Ironically, some of the Puerto Rican indepdentistas (independence advocates) assisted the United States in its invasion of Puerto Rico because they expected that the United States would help to liberate Puerto Rico from its ties with Spain. There was disappointment and disillusionment when it became clear that the United States would not grant greater autonomy or independence to Puerto Rico.”(439)

Back in the U.S., according to historian Paul Kramer, the Spanish-American war and the expansion of American empire faced opposition from those, like Mark Twain, who believed the U.S. to be different from Europe, to be anti-imperial in its very nature. Yet more powerful proved to be those voices who claimed for Americans an exceptional, racial character as English or Anglo-Saxons capable of a better sort of empire than the Spanish.

So the War Department’s census probably did political and rhetorical work. It asserted the capacity of the imperial apparatus to know in detail (nearly 400 pages worth) the island, its resources, its history, its politics, and its people. If Puerto Rico could be known, then couldn’t it also be governed rationally? This census, I think, told a story calculated to ease the minds of an expanding imperial power and to justify extended rule.

(Updated on 9 June 2018)