Super Snoopers in Montevideo

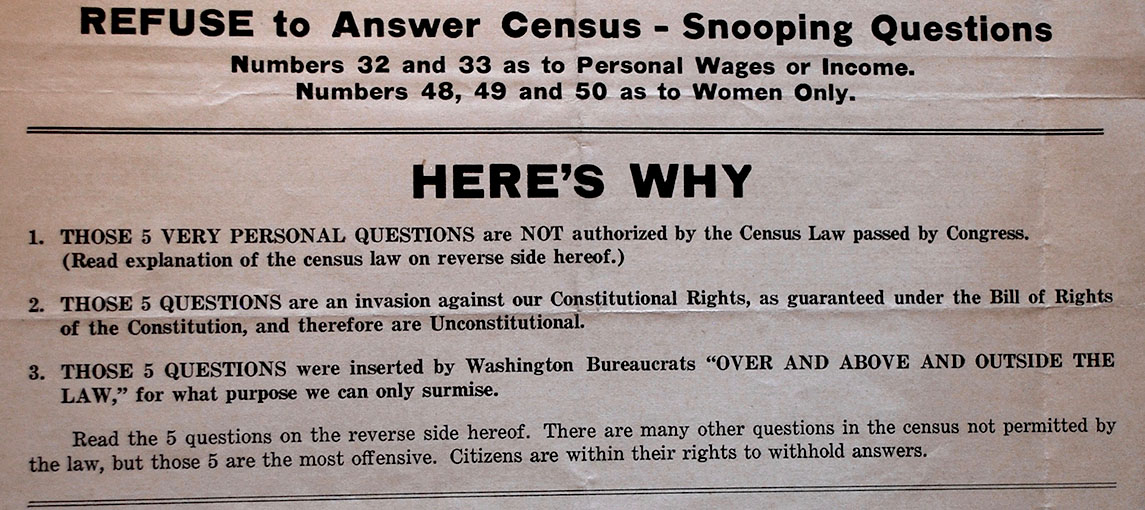

“You’ve Got To Get Mad” screamed a handbill in block-bold letters. The placard traveled along the same blocks where census enumerators roamed in early April 1940. “Stand firm on your Constitutional Rights” it warned. The Constitutional Rights Republican League of Minnesota jeered “Washington Bureaucrats” and their “snooping.” They called on individuals to refuse to cooperate. Few appear to have taken the call to heart. This was a point that census officials celebrated. But as I came to realize while investigating the census returns for small-town Minnesota, the so-called Washington Bureaucrats achieved this success after they preemptively limited their own “snooping.” Many Minnesotans (and their fellow ordinary Americans) may have seen no need to refuse because they could comply with census takers and still keep their household finances secret.

“You’ve Got To Get Mad” screamed a handbill in block-bold letters. The placard traveled along the same blocks where census enumerators roamed in early April 1940. “Stand firm on your Constitutional Rights” it warned. The Constitutional Rights Republican League of Minnesota jeered “Washington Bureaucrats” and their “snooping.” They called on individuals to refuse to cooperate. Few appear to have taken the call to heart. This was a point that census officials celebrated. But as I came to realize while investigating the census returns for small-town Minnesota, the so-called Washington Bureaucrats achieved this success after they preemptively limited their own “snooping.” Many Minnesotans (and their fellow ordinary Americans) may have seen no need to refuse because they could comply with census takers and still keep their household finances secret.

This particular handbill reached the Census Bureau during the first week of the count, but by then officials were well aware of the threat. The storm began brewing two months earlier, on the first of February, when New Hampshire Republican Charles W. Tobey first stood on the floor of the Senate to denounce two questions on the proposed population census that asked for individuals to divulge their wages and to say whether they had earned $50 or more by some means other than wages. Tobey inveighed against the inquiries—“snooping” he called them, and the smear stuck.

Tobey broadcast his charges on primetime radio on 19 February. The next day a Senate subcommittee formed to investigate and hold hearings. Tobey gained allies in the legislature and the press. Opponents of Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal” rushed to join the ruckus: behind the new census questions, claimed an official of the American Federation of Investors, lay “the scheme for political domination of private enterprise.”

The April handbill amplified the already over-heated political rhetoric. Snooping became “super-snooping” and the New Deal officials transformed into “fake Americans” aiming to “hogtie American industry” and “impose an Alien scheme of regimentation” that (here taking a populist turn) amounted to “class discrimination” against the poor. It was an election year, after all. A GOP elephant holding aloft the constitution anchored the handbill, it’s enormous weight supported by an foundational aspiration: “Life Begins in ‘40.” (Spoiler: Life did not begin in ‘40.)

The assault unsettled Bureau officials. “We are under extremely heavy fire because of the income question,” confided the Census Bureau Chief Statistician Calvert Dedrick to a young scholar (named Milton Friedman—yes, that Milton Friedman) at the National Bureau of Economic Research.^^ Dedrick’s staff worried that tough talk in Washington would take its toll on census takers in the streets:

“We fear that the public opinion aroused by the deliberate misconstruction of this question will seriously affect public cooperation with the Bureau, and will make it very difficult and expensive for us to carry through our plans….Some of our men feel rather bitter on this subject.”

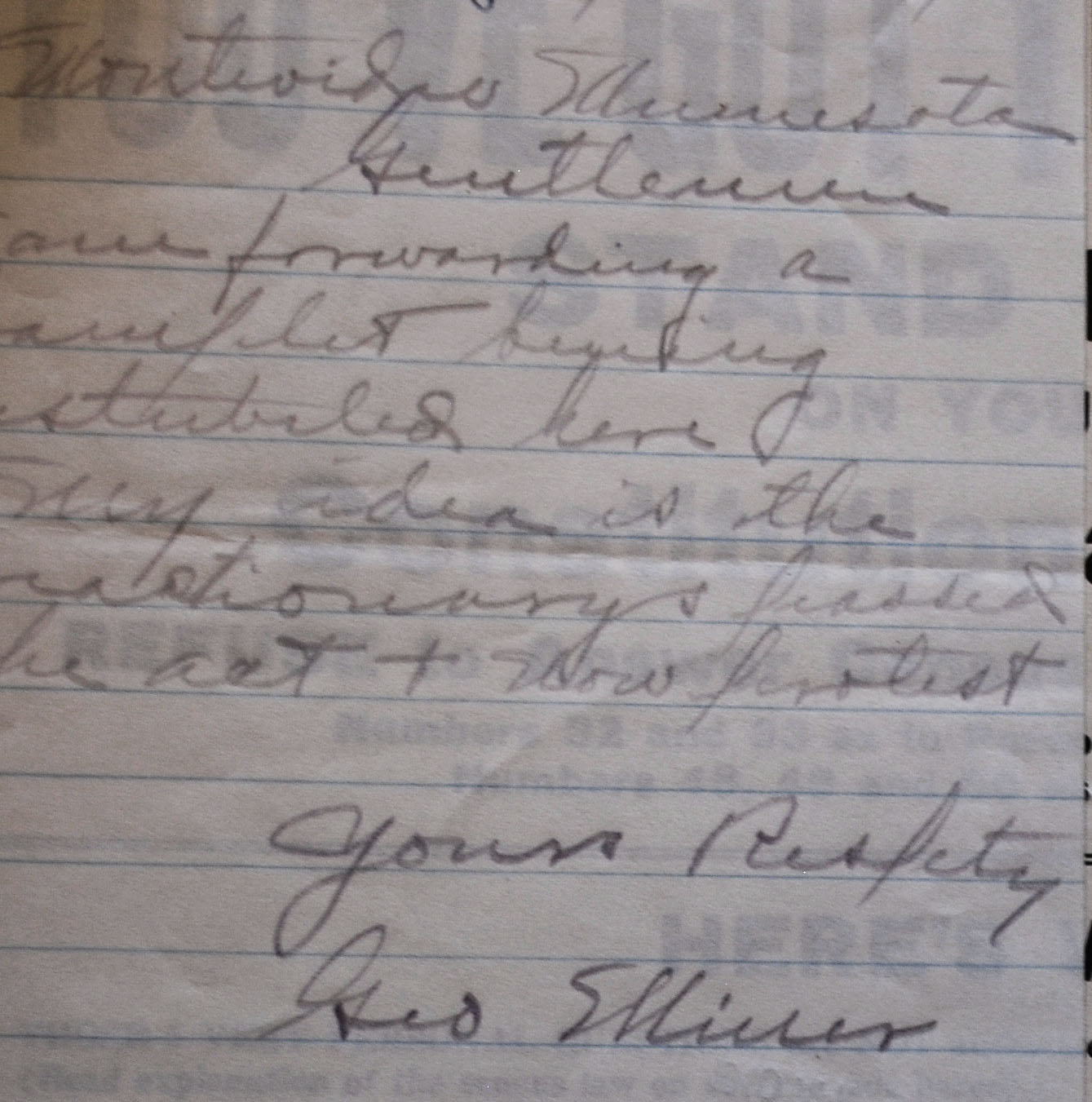

The Census Bureau turned out to have its own allies around the country, though, people like George Miner of Montevideo, Minnesota. He sent Dedrick a copy of the handbill. To him it seemed an unreasonable hypocrisy, that “the reactionaries passed the act and now protest it.”

By the end of the first week of the count, Dedrick sounded optimistic. Citing reports from district supervisors, he told Miner there was nothing to worry about:

Uniformly throughout the United States we are finding the public willing and anxious to cooperate with their government in providing census information which will be for the good of all.

When all was said and done, the Bureau claimed that only 2% of all respondents refused to answer. (Although that figure from the procedural history seems an understatement, according to the Bureau’s own reports: 2.56 million people, or nearly 5% did not report any wage income.) On top of that, about 200,000 people did not trust their wage data to the census taker and insisted instead on mailing their answer directly to the Bureau on a “confidential card.” (That’s not a huge number, but nor is it insignificant. It’s about the same number of people listed as “partner” in the 1940 census.)

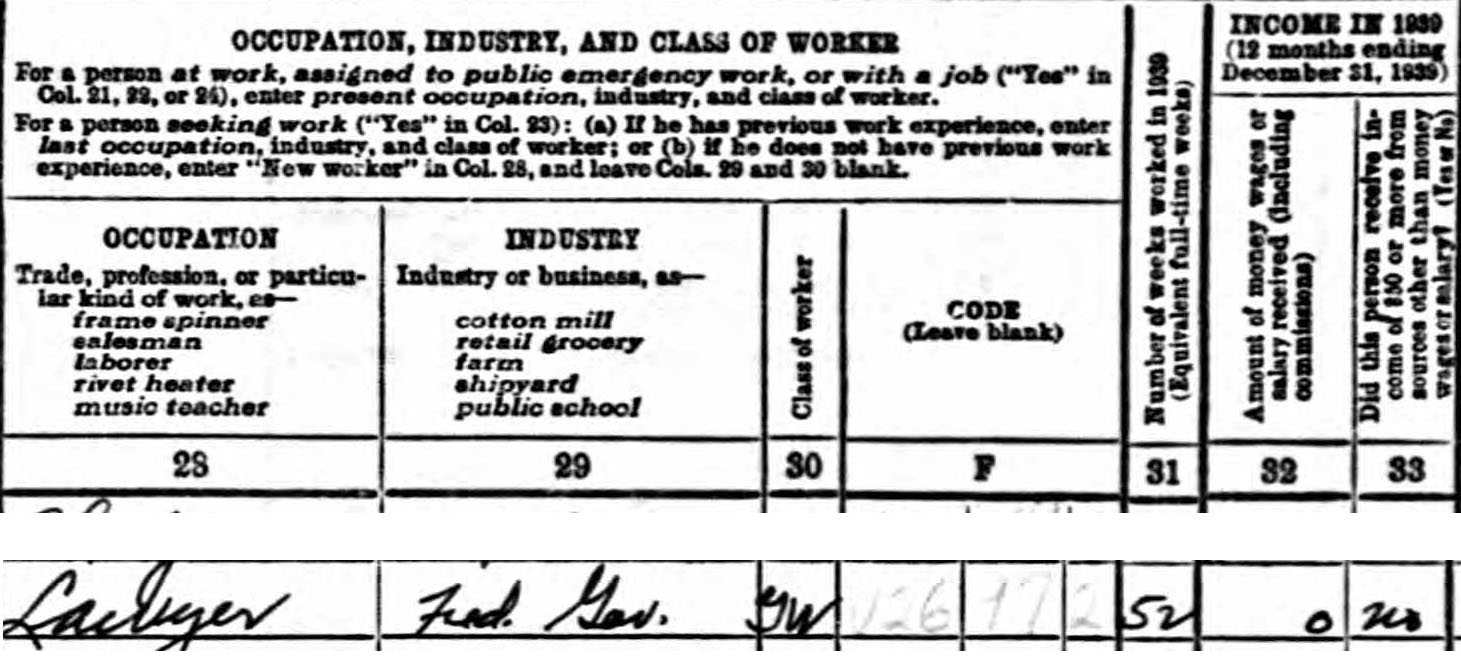

Charles W. Tobey pledged (loud enough that reporters could hear him) that he would evade the income questions. He practically begged the Census Bureau to arrest him for his noncooperation. So far as I can tell, though, he (intentionally or not) did not appear in the census at all. Instead I found Charles W. Tobey, Jr., a lawyer for the federal government living in Arlington, VA. I presume he’s the Senator’s son. He followed his father’s example:

Look at the right-most three columns, above. Tobey Jr. reported working 52 weeks as a lawyer for the Feds, while earning $0 in wages and less than $50 in any other income. Government work might not pay great, but it pays better than that!

Tobey Jr. was so committed to refusal that he wouldn’t even tell the government how much it was paying him.

Mary Rupp was a 51-year-old, single, white woman, living in a small rented apartment on Montevideo’s Park Ave. Most other weeks, Rupp scraped out a living taking orders for ladies wear. She was a “canvasser.” In early April, though, Rupp set aside selling dresses and set to counting her neighbors for the Census Bureau instead. She took down George Miner’s data on 11 April 1940, a week after Miner forwarded the offending handbill to Washington.

I wondered if concerted efforts by groups like the Constitutional Rights Republican League might have increased resistance on the local level. So I began rifling through Rupp’s records for E.D. 12-19.

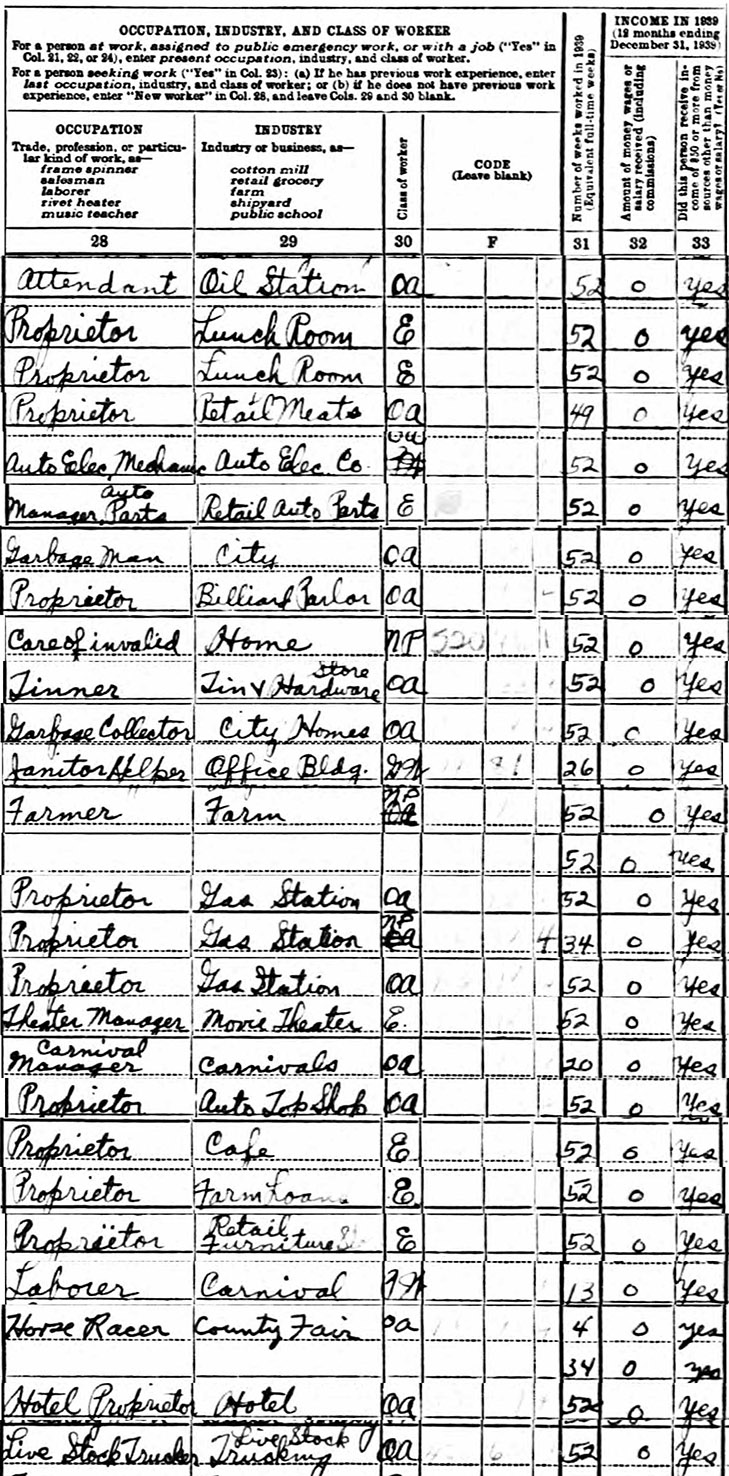

For the most part, as in most of America, Montevideo cooperated. Still I discovered, and as intrigued by, a surfeit of entries like these:

Look at all those zeros! They did not all occur one after the other (as they appear above), but were interspersed throughout the schedules. I’ve collected many, but not all, that occurred. They represent a significant minority, though far from a majority, of all of Rupp’s neighbors who reported having worked. But these folks managed to avoid disclosing their income.

There were some true cyphers: like the two individuals for whom no occupation or industry appears. Others worked outside the system of wages, as was the case with George Harstad who worked 52 weeks at “care of invalid,” probably looking after his 74-year-old father Hogan. George made it clear to Rupp that he worked a full time job, even if he wasn’t paid.

Senator Tobey and his fellow Republicans were not wrong about the class discrimination structuring the census. The income questions were designed to probe the economic lives of workers—people who earned a wage. They assumed a proletariat working class that needed counting, and indeed 38.1 million Americans did work for wages. For fear of reprisals and resistance, though, census officials didn’t dig too deep into the finances of the rich: any income over $5,000 was to be reported as simply $5,000. As a result, just over 400,000 Americans—the 1% of wage earners—escaped from revealing their gaudy salaries to a visiting Depression-era enumerator. For similar reasons, business owners and investors did not have to reveal how much income they received from their ventures. They just had to say whether they earned more than $50.^^^ That concession obscured the true incomes of over 21.7 million people. The petit-bourgeoisie escaped financial scrutiny, too, thanks to this sop to the millionaires. Note how many of those I’ve gathered into the table above list themselves as “proprietors.”

It seems some in the lower classes noted this loophole as well, joining the ranks of the nearly 22 million. They gamed the census, taking advantage of its deference to the wealthy to hide their hard-won, and precious, pittances. That’s my read on the carnies: the carnival manager, the laborer, and the county fair horse racer. Did they truly work on their own accounts, or might their income have been construed as wages? The same goes, perhaps double, for the gas station “Attendant.” Those are just cases that raise my suspicions though. There’s more reliable evidence of gamesmanship. Inconsistencies within Mary Rupp’s district demonstrate the interpretive possibilities open to clever, possibly wary, Americans.

Take garbage collecting. Lloyd H. Eschen, a married 32-year-old, white man with twin 4-year-old sons, said he earned $400 for 41 weeks of work as a garbage collector. He admitted to being a paid worker, and so his wages became visible to the census.

A few blocks away lived Therlo W. Torrey, a 37-year-old, white, native Minnesotan and his wife Mabel and daughter Phyllis Rae. Torrey worked 52 weeks as a garbage collector, but claimed to work on his “own account,” which meant he received no wages. Mary Rupp dutifully reported $0 in wages and “yes” to indicate that Torrey earned more than $50 by some other means—presumably the proceeds from his independent trash pick-up.

Cases like these suggest to me that in the process of gathering answers to the income questions, Mary Rupp collected some garbage too.

But more to the point, her records illustrate that long before Charles W. Tobey raised a stink, Bureau officials made decisions that severely limited their own snooping. There were no super snoopers in Montevideo—but there were many individuals whose economic lives were intentionally left vague and some wily Americans (maybe made more wary by Republican fear-mongering) who figured out how to keep the contents of their wallets to themselves.

^Miner probably never got Dedrick’s response, because Dedrick couldn’t read George Miner’s handwriting. He (quite understandably) mistook “Miner” for “Elliner.” Who knows where Dedrick’s letter ended up.

^^Milton Friedman was then serving as secretary for the “Income Conference” held by NBER and so part of scholarly efforts to define National Income (the forerunner to GDP), efforts first tied to understanding income inequality and later to Keynesian economic management. In later years, Friedman became not only a Nobel-prize-winning economist, but also the intellectual standard-bearer for a conservative politics committed to small government and unfettered markets. (For more, see Angus Burgin’s Great Persuasion)

^^^The 100% sample of the 1940 census, via IPUMS shows that over 73 million individuals answered “no,” 21.7 million answered “yes,” and 37.4 million gave no answer at all. Most of those 37 million were likely children, but some could also be refusals.