Print Capital

Quite a few people who I have spoken with over the last few weeks expressed an unexpected kind of surprise when it came to the outcome of the census citizenship question. Plenty of shocking things transpired: to begin with, there was the fact that the Supreme Court shrugged off the administration’s explanation for adding the question, calling it “more of a distraction”(28) than a proper reason. The Departments of Commerce and Justice appeared to acquiesce to that decision, until a presidential tweet (quoted here) reversed everyone’s course for a few days. Now it seems settled: People won’t be asked about their citizenship on the 2020 census. But another thing that shocked (or befuddled) some people I’ve spoken with was that a printing schedule seemed to have decided the fate of the census. Because questionnaires needed to be printed, there was no time to argue anymore about the citizenship question—a point the administration employed to begin with, back when it hoped to convince the court to quickly get rid of all the lawsuits against it at once. Later, after defeat in the courts, the administration had to accept the weight of its own argument. The forms had to be printed. No one pays any attention to a printing deadline, until it defeats some of the world’s most powerful officials. Maybe the ordinary magic of infrastructure and logistics deserves more of our attention the rest of the time too.

Throughout all this census turmoil, I kept thinking of a photo from 1939, taken in a warehouse preparing for the following year’s big count. Here it is:

I do not know who this census employee is, he of the polished shoes, wavy hair, and natty vest. He poses here in the middle of moving a small packet between a rolling hand cart and a wall of wooden cartons.

Most the cartons in the foreground just say “census” on them. In the background white tags catch my attention, stretching deeper than we can see into the warehouse, each marking yet another large container of materials set to be shipped somewhere. The stamps on the middle boxes name people and addresses in New York and Chicago—perhaps they are en route to the “area managers” responsible for overseeing the technical aspects of the census in those cities. The caption, pasted to the back of the photo, provides more context: “These are some of the 29,000 boxes which are being used to ship questionnaires for the 1940 census. Fifty-six mail cars will be needed to transport supplies for the census.”

29,000 boxes!

56 mail (rail) cars!

Similar exclamations attend nearly every census, and for good reason. It’s a mind-bendingly massive undertaking to track down more than a hundred million people spread across thousands of miles in the space of just a few weeks. Census officials in the mid-century often enlisted military metaphors (“an army of enumerators”) to describe the undertaking, for good reason—in what other field could one find so many people, so much time and talent, mobilized in so short a time? But instead of gathering to fight, the census army gathered to count!

In the 1920s, an engineer named Herbert Hoover took control of the Department of Commerce, and so too of the census. Hoover had made a name for himself coordinating relief efforts and running the U.S. Food Administration during World War I (“Food Will Win the War”). He brought to Commerce an abiding enthusiasm for statistics and data gathering. In his first annual report, the republican appointee Hoover included this comment concerning the recent census just completed by the out-going (democratic) administration: “few persons other than those connected with the census realize the magnitude of the undertaking and the difficulties of carrying it to completion within the period prescribed by law.”

Perhaps Herbert Hoover was just then realizing for himself the depth and breadth of the whole thing. His annual report (in a section likely authored by census employees) explained: the census “involves the printing and distribution of 18,000,000 schedules of questions;” to which the report added the tasks of coordinating 90,000 enumerators, punching 300 million tabulating cards, and publishing multivolume sets of statistical tables that together covered about 11,000 pages. Printing came first in the litany.

18,000,000 forms!

90,000 enumerators!

300,000,000 punch cards!

All that statistical activity required space, lots of it. In 1926, Congress authorized building a new home for Commerce—one meant to be large enough to encompass the census and the department’s other operations (including, believe it or not, an aquarium!).^ “The next episode in this drama will take place in 1932,” wrote a Bureau statistician in evident anticipation, “when the Census Bureau moves to the new home of the Commerce Department, now being completed at Constitution Ave and 14th Streets in Washington.” Perhaps he was eager to look at the fish.

It was a grand new home, to say the least:

The new six-story-tall Commerce Building spanned three large city blocks. In his 2018 book, The Fifth Risk, journalist Michael Lewis described the Department of Energy Building by saying that it looked as if “someone had punched out a skyscraper and it never got back on its feet.” (46) Thinking with that metaphor, the Commerce Building looks to me now like a skyscraper sliced off at its knees, waist, breast, and neck, the slices then set side by side instead of piled atop one another. At the time, the headline for a 31 December 1931 special edition of the Washington Post read: “Size of building baffles writers.” It was (and is) bafflingly massive, just like the census.

But where writers failed, the advertisers sponsoring the Post’s special edition rose to the challenge. Freight trains moved a mountain to the Capital: 686,797 cubic feet of Indiana Limestone and 70,796 cubic feet of Connecticut Granite traveled to DC to become the new Department of Commerce Building. That amounted to 1,570 railroad cars worth, 61,400 tons of stone. It had taken 6 acres of terra cotta “Ludowici Tile” to enclose the new office building. Masons poured and troweled out 30,000 barrels of cement as the new structure rose, brick by brick, stone upon stone.

1,570 cars of stone!

6 acres of terra cotta tile!

30,000 barrels of cement!

The American Radiator Company called it “a fitting monument and an everlasting tribute to the splendid work of our government.” (“Incidentally,” they added, “the American Radiators which will keep the occupants of this wonderful building comfortable and happy, will do the same in your home.”) IBM called it “A Glorious Monument to Commerce.” It looked like a monument, too, or a bureaucratic Greek Temple: from two darker stone lower-stories climbed a sheer, stark white stone and dozens upon dozens of ornamental columns.

Yet by 1940, even this sprawling office/temple could not accommodate the needs of the census. Storage posed a problem, as did computation. Where were all those paper forms and paper cards and calculating sheets to go? Where could the bureau fit all the people and machines responsible for turning forms into statistical tables?

I’m writing this post in Berlin, in my favorite park, a literal machine-in-the-garden sort of spot called Park am Gleisdreieck: a park built atop a railroad tunnel and beneath three elevated train lines. (If you ever find yourself in Berlin and you enjoy seeing vegetation eating away at rail-ties, you should visit this spot.)

Sitting here I’m reminded of the means by which late-nineteenth-century Prussians addressed similar logistical challenges. In 1871, the Prussians too had a fancy new headquarters, according to the fascinating work of my friend, the historian Christine von Oertzen. As von Oertzen explains, even after it rented out another building, the Prussian census bureau had just barely enough space to hold its “5000 boxes with 375 tons worth of roughly 25 millions of filled-in counting cards.”(143)

5000 boxes!

375 tons of counting cards!

They had enough room to keep the cards, but not enough to actually count them—a process that had to be done by hand (which is to say, by many, many hands). The Prussians solved this problem by inventing a kind of distributed computing: they shipped boxes to people’s homes (often the homes of their employees) and hired people in those homes (often the wives of officials) to do the counting, paying a piece-rate for each completed set of calculations. These women became cloud computers, whose existence like so many others was forgotten, until von Oertzen brought it to light in 2017.

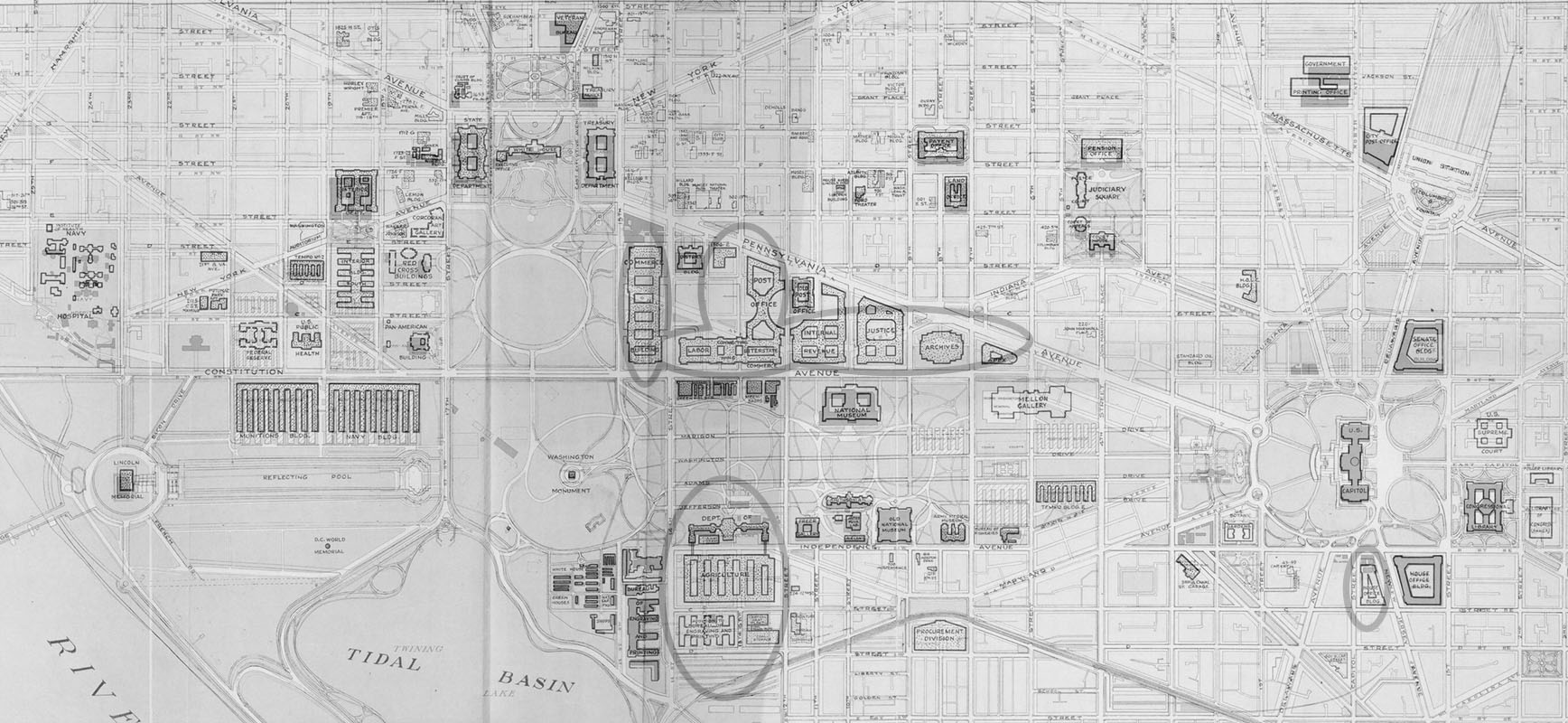

To solve their storage problems, the American census bureau rented space from Woodward and Lothrop, a D.C. department store. The store, which I gather was nicknamed Woodies, had just finished building their new warehouse in 1939, according to Wikipedia. But that Wikipedia entry won’t tell you (as of 22 July 2019) that the census signed on as one of the warehouse’s first tenants. Nor will this Historic American Buildings Survey report. For evidence of the relationship online, you’d have to recognize Woodies’ warehouse at 1st and M st. NE on this 1946 map, where it is marked as a facility rented and operated by the federal government.

If Christine von Oertzen’s Prussians invented a proto-cloud-computing system, then I am tempted to draw a parallel between the Woodies warehouse deal and the digital warehouse services that Amazon supplies to government entities now.

Back in 1939, Woodies saved the day. William Lane Austin, the director of the Census Bureau, mentioned the warehouse in a 1939 letter to his boss, Harry Hopkins (another Secretary of Commerce with the initials HH). “The Bureau is now six months behind in securing absolutely essential space,” warned Austin on July 6. He continued: “The Woodward and Lothrop warehouse building will be ready for our occupancy at the end of this week or early next week. It will house our division of Geography and our Field Division.”

The geographers must have packed up their drafting tools to inhabit new make-shift offices.

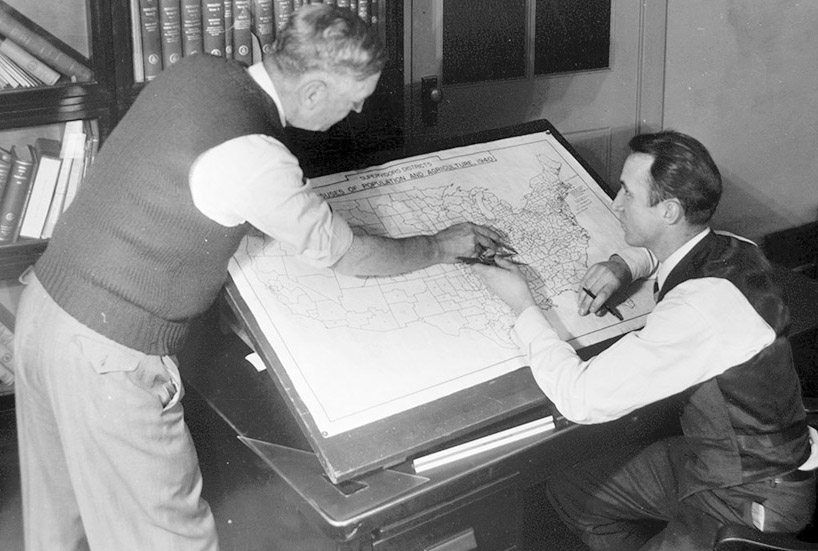

In a photo from that summer, two white men lean over a drafting table, one has silver hair and a knit vest, the other appears younger and wears a striped tie, a suit vest, and has dark brown hair. They are posed as if working on a map in front of them. The junior man holds a compass while the other points. The title of the map identifies it as a United States map that has been divided into Supervisor’s Districts (each numbered, so that an “S.D. No.” can be filled in at the upper right of every census sheet). The photo’s caption doesn’t mention Supervisor’s Districts, instead explaining that the bureau divided the nation into roughly 147,000 enumeration districts (each S.D. contains some quantity of smaller E.D.s, also numbered). “This is to insure against over-lapping activities of census takers, or enumerators, and also to avoid missing any territory,” the caption explains. It continues: “Census enumerators are provided with maps of their districts.” And so we realize another big job: printing more than a hundred thousand local maps to direct the count.

I cannot say for sure whether or not the bureau photographed these geographers in the Woodies warehouse. But the timing makes it possible, even likely: the photo is from the summer of 1939 just as the bureau moved in. And though I’d never noted it before, there is more than a bit of a ramshackle feel to the set-up here. The drafting table seems to block, or nearly block, a door behind it. It’s also oddly placed with respect to the bookshelves in the back. The more I look at it, the more readily I’d believe that this photo offers a glimpse into the life of a map-making unit setting up shop in a department store warehouse.

But as big as the geographic program was, the real reason for the warehouse was the Field Division. It coordinated the enumerating army. A report compiled after the census explained that the division “placed 27 different items in each of 147,000 portfolios, packed and shipped 29,500 shipping cases.” It’s shipped “160 million forms, 2 ½ million letterheads, 33 million envelopes, 350,000 blotters, 18,000 pen points,” and more: over 2 millions pounds of shipping all told, processed by 287,292 man hours of labor over the course of 16 months, beginning in August 1939. It “occupied 36,000 sq. ft. of floor space for assembling, packing and shipping supplies, schedules, instructions, etc.”—which is the size of 3/4 of a football field (not counting the endzones^^).

160 million forms!

33 million envelopes!

18,000 pen points!

I suspect the photo that opened this essay was taken within that 36,000 square feet among those 29,500 shipping cases. I have reason to believe our dandy dresser felt cramped loading and unloading his handcart. Whoever wrote the report, at least, judged the space too small.

When I first started thinking about that photo, thinking about it in the context of the soon approaching 2020 census, I didn’t realize that the logistical backbone of 1940’s “inventory of democracy” was a department store warehouse that the Census Bureau ultimately deemed “inadequate.”

After William Lane Austin sighed in relief to Harry Hopkins that the Woodies warehouse would soon come online, he pointed out a problem. There might be just enough room to supply the enumeration force. But there was nowhere near enough space for the thousands of clerks operating card punches and tabulating machines who, once the enumeration had been completed would turn all those census taker’s hand-written biographies into quantified, statistical facts.

Maybe Austin should have considered paying piece rates to women counting cards in their homes, like the Prussians of 1871. (Then again, a Roosevelt appointee probably would think twice before openly imitating Prussians in 1940.) At any rate, what the Census Bureau really did, that’s for another story… (stay tuned!)

For now, the (entirely understandable) furor about the citizenship question has obscured a major shift transforming the census before our (distracted) eyes. The field division is shrinking and the bringing the tabulating machines (now we call them phones) out of the office and into the American urban, suburban, exurban, and rural wilds.^^^ As Issie Lapowski reported in Wired earlier this year, the Census Bureau has developed what it calls the ECaSE system, which will run on iphones capable of inputting individuals’ census data, encrypting it, and uploading it a central, secure census database. Less printing should result: “The goal is to replace, or at least radically reduce, the 17 million pages of paper maps that the bureau printed out for the 2010 census and the 50 million paper questionnaires that field workers had to tote around with them.” And fewer enumerators: “because the tools are expected to make field workers more efficient, the bureau expects to hire roughly half as many people as it did in 2010.”

>17 million maps!

>50 million questionnaires!

1/2 as many census takers!

We’ll see…

If we take the time to look.

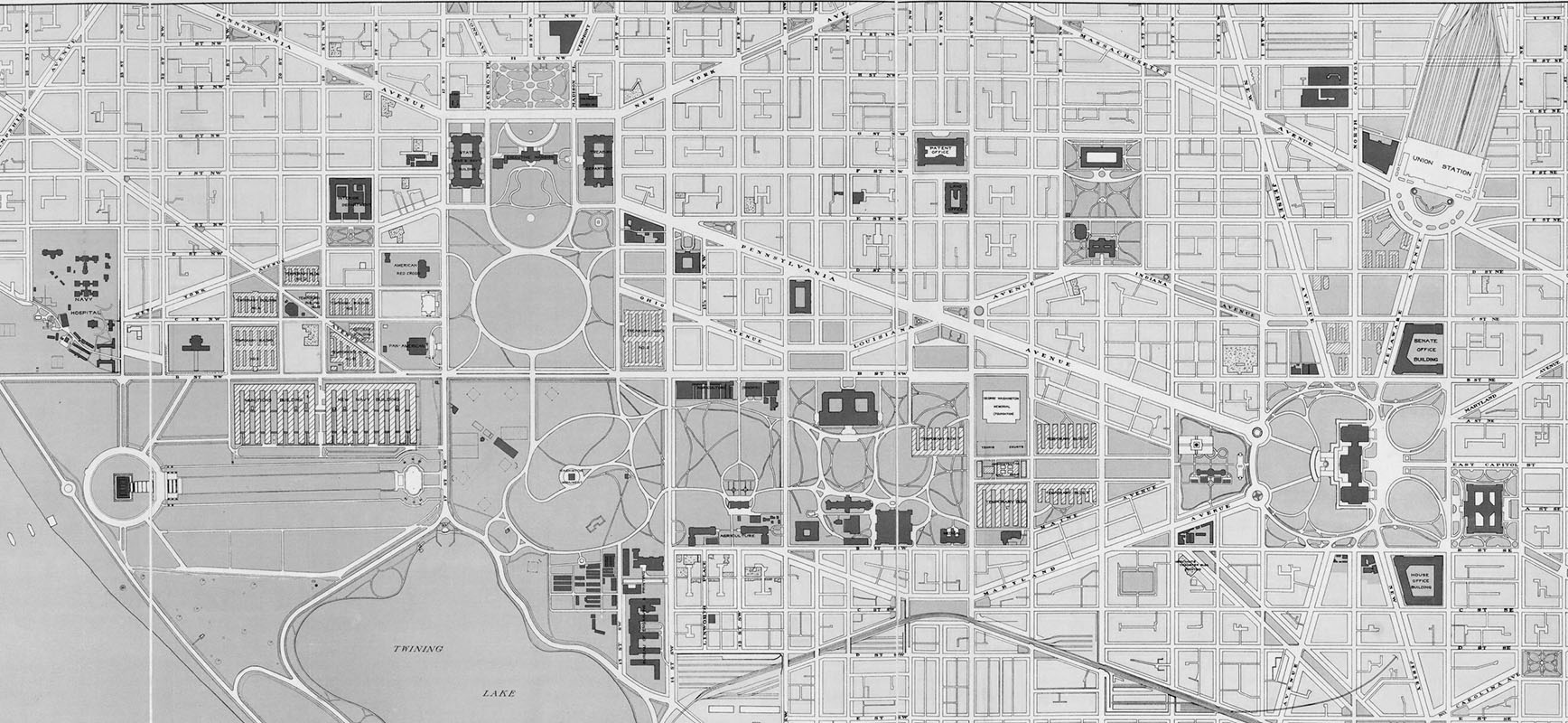

^The 1926 Public Buildings Act provided for the new Commerce building, and transformed the nation’s capital. In 1927, the Capitol area looked like this.

Ten years later, federal employees reported to new offices for Agriculture, Commerce, Labor, Justice, IRS, and the newly created National Archives. The so-called Federal Triangle was born.

No wonder Senator Charles Tobey of NH railed against a new breed of “Washington Bureaucrat”—as these new buildings sprouted like weeds, it must have seemed like office workers had taken over the city.

^^I think it was the historian Richard White who once wrote that Rhode Island served nineteenth century Americans as a basic unit of measure. Every other state or territory was measured in terms of how many Rhode Islands could fit inside. For smaller areas in our era when only a tiny fraction of individuals are farmers (and few have a visceral sense of the size of an acre), the ordinary American unit of comparative area has become the football field.

^^^We’ll leave aside for the moment another fundamental change that the field division undertook in 1960 when enumerators stopped asking questions of every individual and instead just handed out a questionnaire to be completed and picked up. Eventually, the forms arrived and were returned in the mail—the postal worker replaced the census taker. The size of the field force kept growing though, as the Census Bureau invested more resources into attempting to make sure that hard-to-count groups were, in fact, counted. (On all this, see Margo Anderson’s The American Census, chapter 8.)