Scientists in the Census Office

Joseph A. Hill was no slouch. Born in 1860, Hill had earned bachelors and masters degrees from Harvard before crossing the Atlantic for Halle in Germany, where he earned his Ph.D. in 1893. Upon his return to the United States, Hill began lecturing, first at the University of Pennsylvania, and then at his alma mater. It must have been Harvard’s president at the time—Charles Eliot—who nominated Hill to join a group of the nation’s most promising young social scientists selected to serve in the 1900 U.S. census.

Hill’s new boss in the census offices was, however, significantly more accomplished. He was also a year younger than Hill. Walter Willcox, born in 1861, had a bachelors and masters degrees from Amherst College, a law degree from Columbia, and a Ph.D. from Columbia too. He too made an intellectual pilgrimage to study German social science, in his case spending a year in Berlin in 1889-1890. Willcox finished his PhD in 1891 and immediately joined Cornell’s faculty. He rose swiftly to prominence in both the American Economic Association and the American Statistical Associations, publishing a raft of influential articles in the 1890s.

Both men understood themselves to be chasing objectivity and their chariot was science. Statistics promised them a “view from nowhere,”—here I am thinking with the work of historian Lorraine Daston. But Hill and Willcox came from somewhere: born on the eve of the Civil War in New England, educated in elite institutions, and in Germany. They were white, native-born, men coming of age just as the North largely turned away from racial equality and made peace with Jim Crow, white supremacy, and anti-semitism. That was where their views came from.

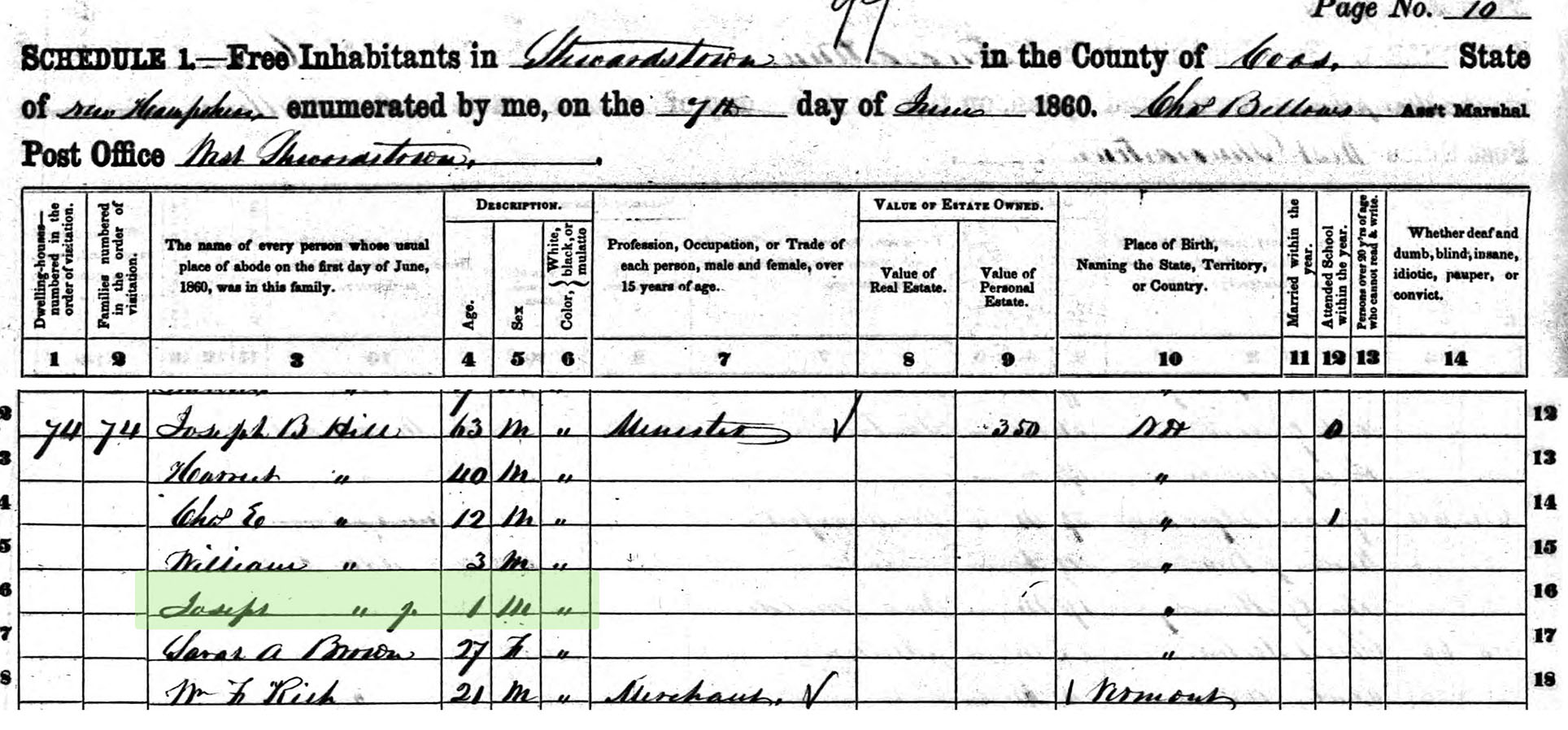

Hill, because he was older, appeared in the 1860 census—the last census to include a separate schedule (form) for enumerating enslaved people. He and his family appeared on a schedule for free people.

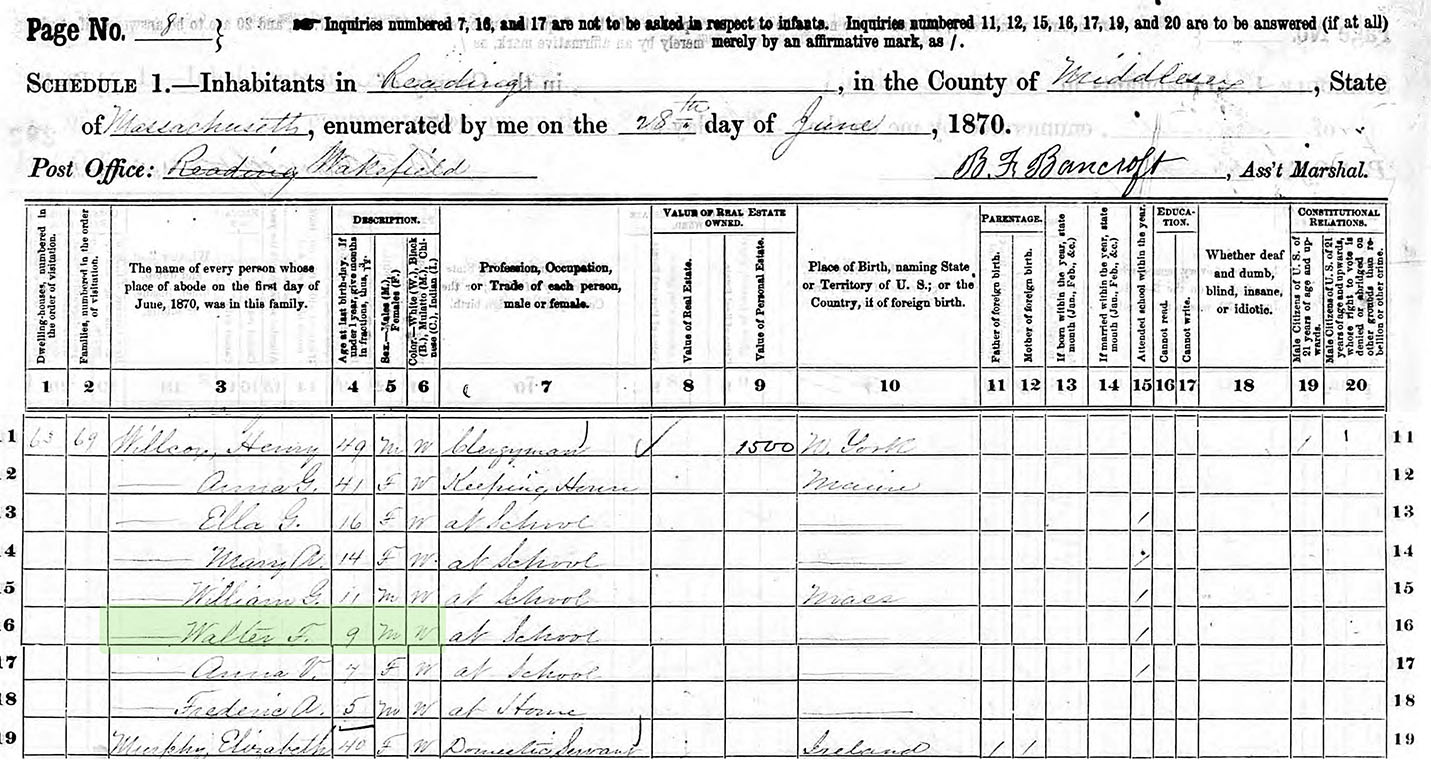

Willcox only appeared as a 9-year-old child, the son of a minister–just as Hill was. Willcox’s household also included an Irish domestic servant named Elizabeth Murphy.

The context they grew up in left its mark. My search for biographical material on Willcox led me to Mark Aldrich’s 1979 article, which described how in 1896, Willcox championed the publication of Frederick L. Hoffman’s Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro, a massive statistical study that posited the inevitable extinction of African Americans outside of slavery. I also came across Willcox’s name this week while reading Khalil Gibran Muhammad’s masterful history The Condemnation of Blackness, in which Muhammad dissects a paper Willcox presented in 1899 on “Negro Criminality”–one that helped establish the criminality of Blacks as a significant national problem, and a problem to be addressed with statistics. This was the work he became most closely identified with just at the moment he began working on the census. Aldrich called Willcox “far and away the most important economist promulgating scientific racist arguments.” And in a fond obituary of Willcox, by the government statistician Stuart Rice, I found an odd story of Rice riding a steam ship down the Mississippi in the early 1960s. On that trip, Rice visited a Southern plantation, and was pleased to discovery on its shelves a book filled with statistical essays on the Negro “problem.” The first four had been written by Willcox, and the book was published by a prominent Southern planter-intellectual who Willcox mentored.

Hill, who published less, has left less of a record that could situate him intellectually before he joined the census.

Willcox joined the census in 1899 as one of five chief statisticians. In the mid-1890s, Willcox joined a chorus of scholars calling for a rebirth of census operations. When each prior census had been completed, the entire operation shut down, its newly skilled and experienced clerks and statisticians scattered. Willcox and his peers wanted census staff to persist. They called for a permanent statistical bureau that would be able to count the nation every 10 years, as required by the Constitution, and also maintain the nation’s statistical records in the years between census counts. At the same time, they hoped to separate statistical work from the vagaries of politics. In the words of Carroll Wright, a leading government statistician, explaining the necessity of a permanent, independent census bureau: “the scientific character of census work demands that it be carried on by an officer not subject to the political changes which come to great departments.”

It had been Willcox’s idea to siphon talent from the nation’s universities to build the census into a more thoroughly scientific institution. According to a celebratory article written on the occasion of Willcox’s 100th birthday (he lived to 103!), Willcox “obtained the approval of the Director of the Census, William R. Merriam, to arrange for analyses and interpretations of the census supplementary to the routine reports on population and vital statistics. In order to carry out this task the Bureau of the Census enlisted the help of the presidents of some 20 universities, inviting them to submit the names of outstanding graduate students who might be willing to assist in the analysis.” Joseph Hill–though not a graduate student, and in fact a Ph.D. like Willcox, belonged to that group, alongside future luminaries like the economists Wesley Mitchell and Allyn Young. In Hill’s later recollection, he was “one of a number of college graduates who had specialized in economics or statistics and were appointed upon the recommendation of the Presidents of the several colleges or universities to assist in the analysis and interpretation of the census figures.”

Most of the young scientists served their time in the census and then departed, but Joseph Hill stayed on, beginning a career that would endure for 40 years. The census, too, stuck around. In 1902, the 1900 census transitioned into a permanent Census Office, later renamed the Bureau of the Census, or the Census Bureau as it is now commonly known.

Before that happened, in 1901, Willcox and Hill were on their own completing the work of preparing census results when the time came for Congress to apportion itself. Apportionment (or reapportionment, the two terms are used interchangeably) was the reason there was a census in the first place. Article 1, section 2 of the U.S. Constitution declared:

“Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons. The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct.”

The Fourteenth Amendment later revised this section, removing the so-called Three-Fifths clause, which had been there to govern the counting of each enslaved person as only part of a person. In practice, the census that Willcox and Hill worked for had little to do with taxes. But it still served as the basis for allocating seats in the House of Representatives.

The challenge, Willcox and Hill soon discovered, lay in translating the the census’ population count for each state into totals of representatives for each state. First, it was necessary to decide how many representatives the next decade’s Congresses should have in total. The House grew most decades just as population grew. By simple division, each state usually would be owed some whole number of representatives and also some fraction of a representative. But it was not possible to allocate fractions of a representative. They came only has whole persons each representing only one state. Which state, then, among all those owed a fractional seat in the House would actually get one?

Apportionment doesn’t appear to have been much on the minds of social scientists and reformers. The topic does not appear at all in the American Economic Association’s 1899 report on the census. Willcox, who wrote the chapter on population worried about abstruse technical definitions of population and discussed statistical measures like the “center of population.” He looked into measures of migration internationally or within the nation, and to data on when groups (meaning “Whites” and “Negroes”) married. But he never mentioned the necessity of determining apportionment figures. It may be that Willcox was just a clueless intellectual in this case, missing the big practical problem. But I think it is also likely that Willcox did not not notice apportionment, because apportionment was Congress’s political task, not a statistical endeavor.

The events of 1900 made Willcox and Hill question that division of power.

In Hill’s later retelling, he and Willcox presented Congress with a series of tables showing how many seats in the House each state deserved depending on how big Congress decided to make the house. They employed a method (an algorithm) for generating those tables that Hill called “the rule of 1850” (after the year it was first employed). It was also called the “Vinton” or “Hamilton” method, and is described by the Census Bureau here. In short, it was a method premised on dividing the population by the number of representatives, then dividing each state population by the resulting number, handing out representatives to each state according to the whole number each deserves, and then handing out each remaining seat in order to the state with biggest fraction left over. Theoretically, all the politics then lay in the debate over the number of seats. Once one chose that number, the method (working on the data) did the rest.

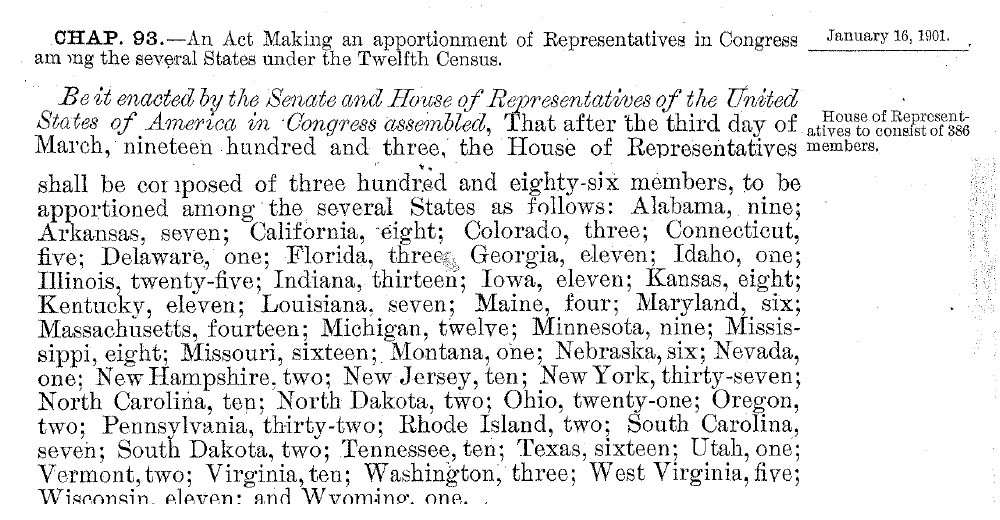

Congress did not see it that way. The first bill for a new apportionment tried to prevent the growth of the House, allowing for 357 representatives, as already were. The bill used the “rule of 1850” calculations, just as they were. But a rival bill beat it out. It won over the House by created 29 new seats and, thereby, ensuring that no State lost a seat—which not incidentally meant that no incumbent House member would have a congressional district pulled out from beneath their feet. Congress got this new 386 person House by a circuitous route, though. It took the table that Willcox and Hill prepared for a house of 384 people and then granted an extra seat to Nebraska and Virginia. Hill noted that in the tables they produced, both Nebraska and Virginia were owed more than 0.5 of a representative. That is, they each had a “Major Fraction” left after the initial allocation of 384 seats—and they each got a full representative in the final bill.

That new law looked like this:

It listed states in alphabetical order; it said how many representatives each state would have in the next Congress (which lasted two years, until the next House elections) and for the 4 Congresses after that. In this way, Congress reinvented itself for the next decade, as was its Constitutional duty. The 1901 law said nothing about how Congress got to the allocation of seats it agreed to.

Hill and Willcox seem to have been dumbfounded, scandalized. Apportionment had not in the past been a scientific problem. Henceforth, they would make apportionment a statistical, scientific problem. It was too important to be left to the politicians alone.

Each set out to design a new method: a method that would provide the right answer, no matter what; a method that Congress would not overrule.

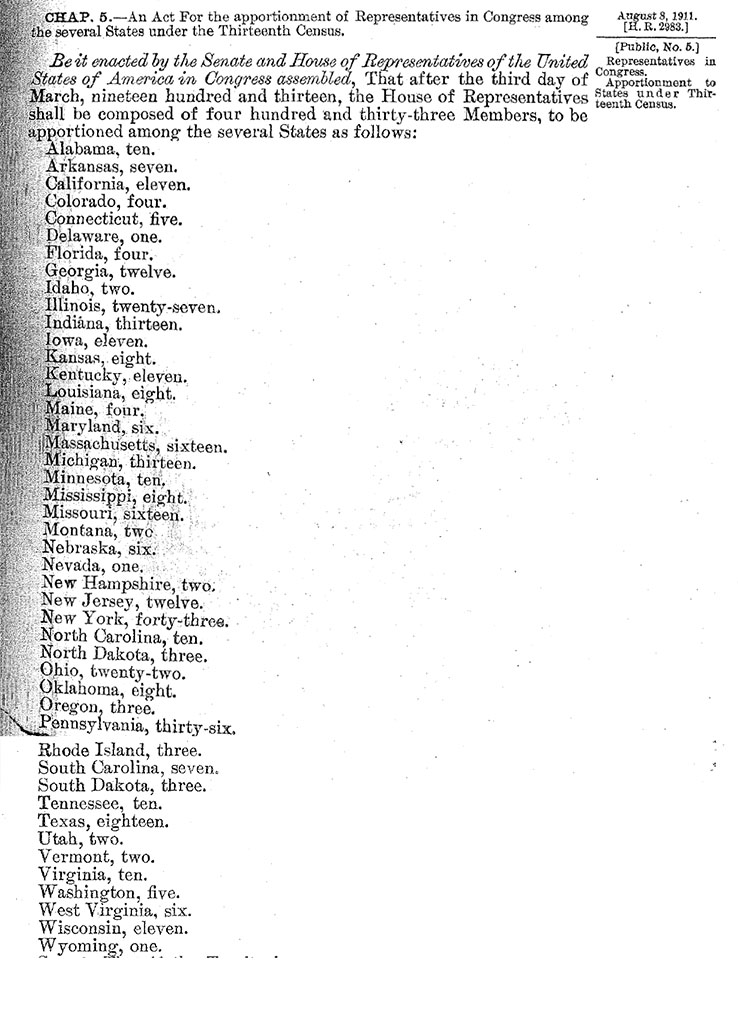

The 1911 apportionment bill was did not look much different from the one passed a decade earlier.

Here it is:

Congress still listed each state in alphabetical order, still assigned each a set number of representatives, still did not explain how it arrived at that number.

For Walter Willcox, though, the bill was a victory for science. His calculations for the apportionment employed his own method, one that he called “the Method of Major Fractions” because it ensured that any state which was owed at least half a representative got that representative. In a report presented to the House of Representatives on 25 April 1911, Willcox wrote:

“The history of reports, debates, and votes upon apportionment seems to show a settled conviction in Congress that every major fraction gives a valid claim to an additional Representative. This conviction has controlled the final apportionment, I believe, on every occasion since and including the apportionment based on the census of 1840. It has been followed even when to follow it has entailed some departure from the method on which the computations were based, as happened in 1872 and 1901.”(7)

Willcox hoped his new procedure would prevent any further “departures” from computational method. He hoped it could be proven to be the one best way to apportion Congressional representatives. To that end, he began gathering academic allies. He solicited the opinion of Cornell’s mathematicians and decided they liked his method best. He went to the American Economic Association’s annual meeting in December 1915 to deliver his presidential address and win the room to his cause. There he bragged that his tables had been “accepted in 1911 without any opposition in committee, House, or Senate” and he went on to list their theoretical qualifications. He wanted their agreement that his method was not only a good one, but “the correct and constitutional method of apportionment.” His method was the method, his algorithm, the algorithm.

Once everyone agreed with him, Congress and politics could be removed from the system entirely. Science would reign.

He explained: “It is now possible for Congress to prescribe, in advance of an approaching census, how many members the House shall contain, to ask the Secretary of Commerce to prepare a table apportioning just that number in accordance with the method of major fractions, and to report the result to Congress or announce it by executive proclamation.” (16) He thought this method would prove particularly useful if and the size of the House was capped, when disputes could no longer be solved by just added seats. He was, in the long run, right about the importance of an automated system in allocated seats in a fixed House.

But before science brought stability to the system, it would play a key role in the system’s decade-long collapse.

This post is published under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license by me.