One Nation, Mature and Manageable

The census of 1940 proved to Stuart Chase that the U.S. population could now be accurately predicted. Of course, he was wrong^, but he did not know that. More importantly, the (wrong) predictions he now believed pointed toward a conclusion he was glad to embrace. America was on the path to maturity, and as a mature nation it not only could be better managed by a new technocratic elite, but indeed would need to be managed.

(^How wrong? Chase quoted predictions placing the 1980 U.S. population between 133 and 153 million. By 1980 there were actually well over 226 million! Higher than predicted birth rates in the postwar decades and relaxed restrictions on immigration after 1965 explain much of the difference.)

This is what maturity looked like:

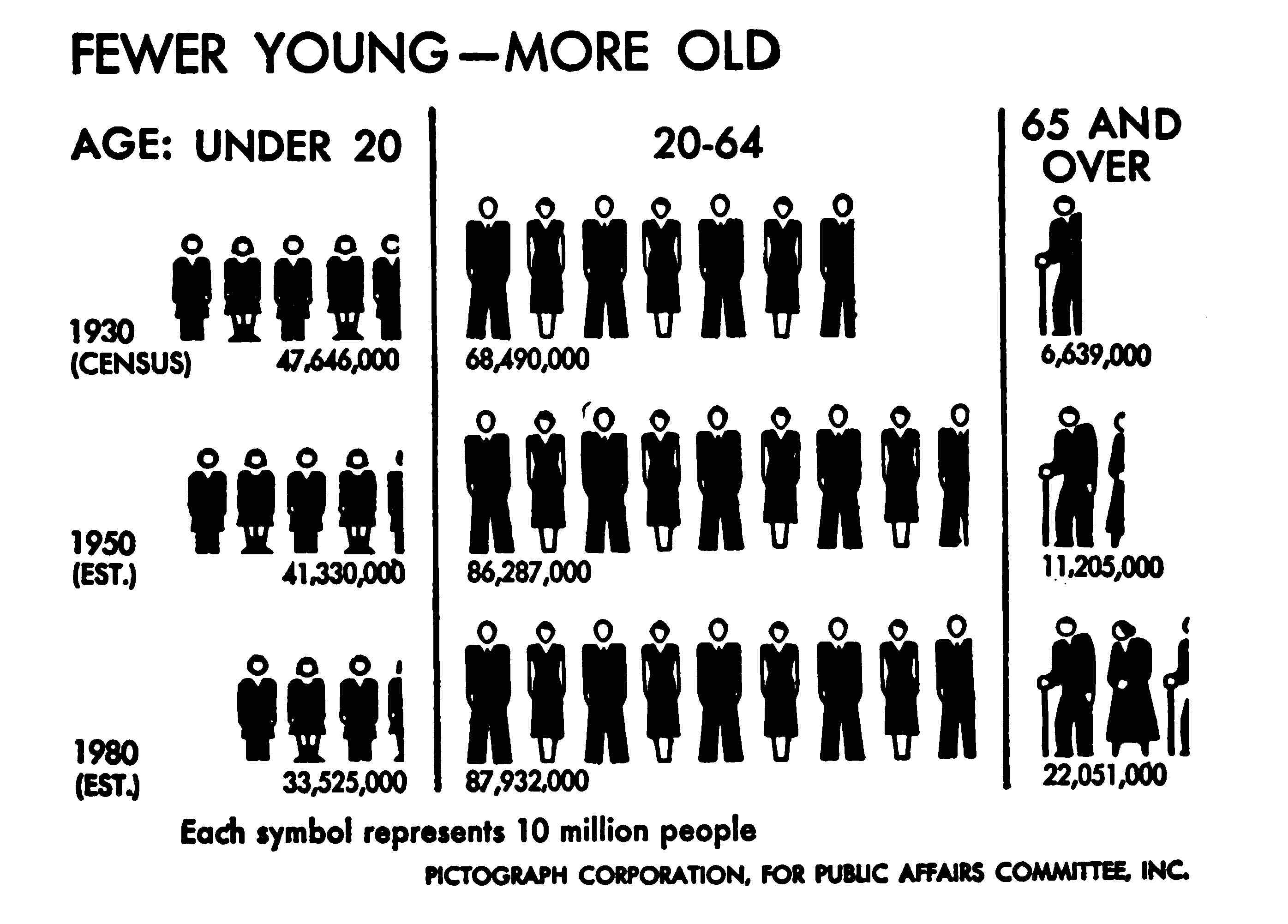

Americans were getting older.

Chase also meant that the nation, like a person, was entering a new phase of life. It had “grown up”:

“The 1940 Census is one of the great landmarks of American history. It proves that we have grown up. The problems of maturity are different from the problems of adolescence, but who will they are more difficult? We are presented with a grave threat and a great promise. Maturity often brings wisdom. Shall we be wise enough to avoid the threat and seize the promise?” (28-29)

It did not bother Chase that “mature” could mean more than one thing. He played with those multiple meanings. He saw them as interrelated.

Influential economic thinkers, like Chase, had begun talking about a “mature economy” in the context of trying to make sense of the Great Depression, especially after a 1937 recession crushed the hopes of those who thought the worst had passed. The maturity concept careened into the national conversation when the Harvard economist Alvin Hansen testified in 1939 before the Temporary National Economic Committee, an investigation by Congress and the White House into the concentration of economic power (and what to do about it). Hansen, according to historian Tim Shenk, warned of “dangerous times” ahead for a nation trapped “in the midst of powerful forces in the evolution of our economy.”(227-228)

Economic maturity came on the heels of the “closing of the frontier” in 1890 (itself an idea invented by the census) and along with slackening birth rates and strict limits on immigration. As Hansen told fellow economists in December 1938: “We are passing…over a divide that separates the great era of growth and expansion of the nineteenth century…” The theory went: without new places and people to exploit, investment waned while easy and reliable economic expansion evaporated. Unless something changed, unless someone stepped in, the United States would be stuck, economically speaking. The government could maintain employment by increased investment. Technological innovation, supported by the government, could build a new (even “endless”) frontier.

Some social scientists volunteered their services to guide the nation into a thriving maturity. Hansen wrote:

The great transition, incident to a rapid decline in population growth and its impact upon capital formation and the workability of a system of free enterprise, calls for high scientific adventure along all the fronts represented by the social science disciplines. (15)

Such arguments set in motion the process that won for economists, their ideas, and their tools the important political roles they now enjoy.

The experts constituting the National Resources Committee in 1938 cheered the way that population research was elbowing its way into governance:

Research in population and in other social science fields has been advanced by a new sense of public responsibility for conditions affecting human welfare. The results of this are seen in the extension of public health activities, education, the social security program, and in many other developments. The need for more systematic investigation relating to the soundness of public works planned for future needs as well as that relating to private enterprises, creates further demand for more extensive and more accurate demographic data. These changes are leading to an increased emphasis on population research, both in the work of governmental agencies and in the plans of foundations, universities, and various local agencies. (16)

Yet all involved admitted that there was still so little data about the nation’s economic and demographic systems. There was so much to learn before anyone could attempt to manage the United States as if it were one of massive corporations that had sprung up at the turn of the twentieth century. As Chase wrote, “But we have had very little experience in managing intensive investment, little experience with a mature economic system. What experience we got in the 1930s was not very pleasant, partly because so many of us refused to face the readjustment.” (25)

Maturity required management. Government would to take charge. Expert planners would have to be the new managers. Chase continued:

“The gross effect of these changes is likely to be more of the same medicine over which we have made such wry faces in the past eight years—government planning and control. “A stationary community needs more careful planning than an expanding one. It needs most planning of all at the outset, to meet the dangers of transition. There are now some 132 million citizens to be protected. To some of them the changes in business will be a life and death matter.” (25-26)

The Census Bureau saw itself as key aid to planning and management. As a 1940 census film explained, the census provided “unbiased facts to measure markets for business and the farmer, plans of school and health officials, the needs of local governments, facts to guide the lawmakers, facts from which a free people can count its gains and chart its future….”

Look for much more in posts to come about census revolutionaries dreaming to make a more scientific census, one fit for managing a mature nation.