Controversial Questions

The 2020 census tumbled into the news again last week. A new question about citizenship had joined the list that all Americans would have to answer, but e-mails made public in the course of a lawsuit cast doubt on how the question got there. Critics of the question cried foul, and I joined them. But as this new census controversy intruded on my Twitter feed, I could not help but also see its similarities to the income question spectacle of 1940. Weren’t we witnessing the drama of another controversial question? Then I stumbled upon a document in the Commerce Department papers (housed in the FDR Presidential Library) that reminded me of a different controversy: a still-too-little-known fight (despite the heroic historical sleuthing of Margo Anderson and William Seltzer) to preserve the sanctity of individuals’ census responses from prying eyes at the FBI. I wanted to know which of these historical census scuffles would allow us to best see our present quandary through fresh eyes? Was this another contested question or another case of law-enforcement encroachment? As I dug deeper, I decided it was neither …

Here’s the context for the current controversy. Last March, Wilbur Ross—the Secretary of Commerce—announced that the next census schedules would require each person to say whether or not they were an American citizen. Experts revolted—so much so that even the conservative think-tank the American Enterprise Institute failed to find anyone on its staff willing to defend the new question. Fearing that the question could cost them both political power and federal funds, nineteen states and 10 cities filed suit against the Department of Commerce. Critics all believed the new question would scare away non-citizens (and maybe others too) and make it even harder to count every American.

The Census Bureau has not sought citizenship information on the decennial census form that goes to every household in the country since 1950….As Defendants’ own research shows, this decision [to add a citizenship question] will “inevitably jeopardize the overall accuracy of the population count” by significantly deterring participation in immigrant communities, because of concerns about how the federal government will use citizenship information. (2)

These news stories ran while I was still investigating Republican Senator Charles W. Tobey’s campaign against the 1940 income question. So it’s hardly surprising that I began thinking about parallels between the 1940 question controversy and today’s.

I’ve already written about the income question controversy, but here’s the important stuff you need to know for now: Spurred by the advice of an expert advisory committee, Bureau officials decided to ask people how much they had earned in wages in 1939 and whether they had other sources of income—both questions designed to shed light on Depression-era unemployment and underemployment. Professional marketers, organized labor, and economic thinkers who blamed the Depression on underconsumption all thought income data could help them too. But Tobey called the question unconstitutional, an egregious invasion of privacy. He appears to have hoped that “Census snooping” might turn into just the sort of issue that would send wary voters running into the Republican camp that November. My time in the papers of Franklin Roosevelt’s Secretary of Commerce in 1940—Harry L. Hopkins—confirmed my sense that the income question furor did not just dominate the news in the two months leading up to the census count in April; it sucked top administration officials, including Hopkins and even the President, into its maw.

Here was a controversy, with potential electoral implications, all stemming from a decision to add a new census question. It sounded a lot like the situation I read about in the news.

Then, just as I began composing a “Census Story” in my head setting the citizenship question next to the income questions, another set of documents offered a comparison to our present day that struck me as even more revealing.

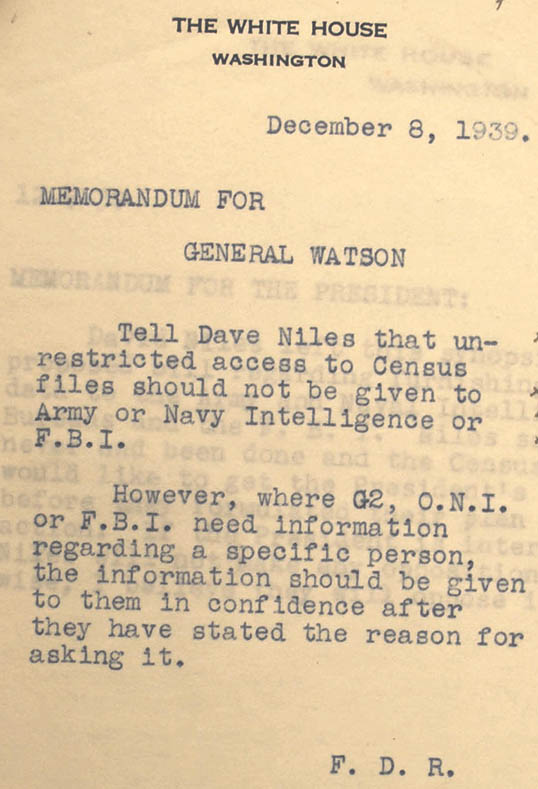

In December 1939, as a dawning world war cast its shadow across the sea, the Attorney General’s office quietly grasped for new powers. It passed around a proposal to amend existing legislation such that the FBI and the military intelligence agencies could gain access to individual census responses for investigations of suspected espionage. President Roosevelt seems to have thought it wasn’t such a bad idea: (Note what comes after the “However”…!)

We have no idea what FDR intended with this note. The existing census laws made it plain that no government agencies had a right to see individuals’ information. Was he authorizing disclosures nonetheless or merely advocating that any new law should require that intelligence agencies explain themselves before gaining access to documents?^ There’s no way to know for sure.

It’s hard to believe, though, that Census Bureau officials, on the eve of 1940’s big count, would have cooperated without a fight. The proposal shocked them, as it did officials in the Departments of Labor and Agriculture. Farmers and workers, those last departments said, might not like the census so much if it were used so overtly for surveillance. The strength of the census, according to the Secretary of Labor, “depends largely upon its universality and the cooperation of the public in giving full and truthful information.” You could kiss universality and cooperation goodbye, officials feared, once ordinary Americans (and private businesses) knew that their answers to enumerators might end up on the desk of J. Edgar Hoover.^^

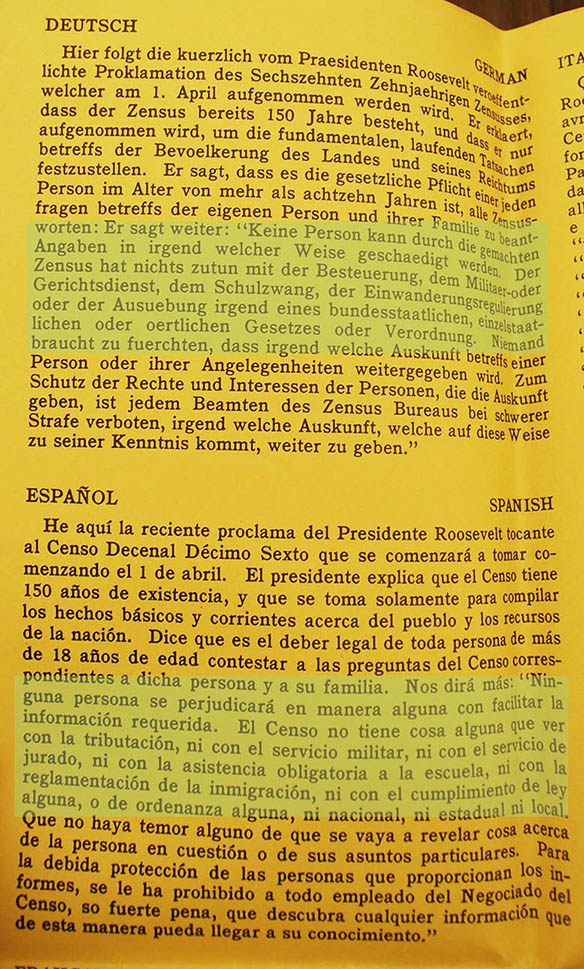

As if to prove their point, posters (authorized by the President) began appearing all over the United States bearing Roosevelt’s 1940 census proclamation. Printed in its entirety in English at the center, the posters also displayed an abbreviated version in 22 other languages. On the poster, Roosevelt announced that it was the duty of all adults to answer the census taker’s questions. But he also (like his most recent predecessors) assured all who cooperated that:

No person can be harmed in any way by furnishing information required. The Census has nothing to do with taxation, with military or jury service, with the compulsion of school attendance, with the regulation of immigration, or with the enforcement of any national, state, or local law, or ordinance.

Here’s what that looked like in German & Spanish. I’ve highlighted FDR’s assurances.

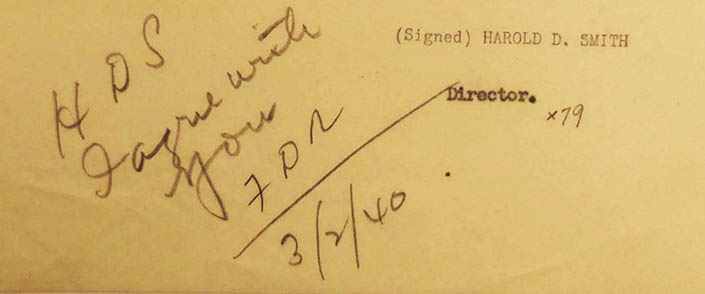

The next time the Attorney General’s proposal came before Roosevelt, an advisor reminded the President of his own proclamation. “It does not seem to me,” wrote Harold D. Smith,”that that the enactment of the legislation proposed by the Department of Justice should be considered as being in accord with your program.” Kill the bill, he recommended.

Roosevelt scrawled out his reply:

Roosevelt’s commitment to confidentiality clearly did not run deep. (That would become tragically clear when the U.S. entered the war.) But for the time being, the power of the then-standard Census Bureau assurances to the public won FDR over. Precedent swayed the President—precedent preserved by “Washington Bureaucrats” who were being castigated by Tobey and his Republican allies.

The more I thought it over, the more I came to believe that these two comparisons only served to highlight what was so different about today’s citizenship question.

The point of the income question had been (from its inception) to procure new, potentially useful information for governance. It drew the ire of politicians and some citizens for requesting details that felt too private for some. The politicians also gambled that the resulting controversy would win votes for the opposition party in a presidential election year. Elites protested being counted with special fervor. Ultimately though, the question survived, even if attenuated, with the full support of the federal bureaucracy.

In the second comparison, the Attorney General also pushed for census reforms that would provide the nation’s intelligence officers with useful information. They wanted to spy on potential spies, and the census offered a ready tool for doing exactly that. Their plan failed, however, because it threatened the success of the enumeration. Neither the President, nor the Attorney General, intended to mess up the census. On the contrary: they wanted a complete census so that they could use it for policing.

The point of today’s citizenship question, in contrast, appears to be to impair the census, to making even more daunting the already Herculean labor of counting every person living in America. No desire for information and no body of experts called it into being. The question for us now is: can the federal bureaucracy effectively stand up for itself and for the integrity of this crucial count?

^I’ve sketched out the dispute here, but for space have left out much of what happened. To read a much more detailed explanation of the arguments about the bill and a fuller timeline of events in the executive branch, see Margo Anderson and William Seltzer, “Challenges to the Confidentiality of U.S. Federal Statistics, 1910-1965,” Journal of Official Statistics. 23, no. 1 (2007): 1-34 at 11-16. Anderson and Seltzer argue that news of the internal debates about loosening confidentiality protects may have spurred Tobey into action in the first place. Tobey, though, did not bring up the Attorney General’s failed plan until the Census was already well under way.

For an overview of some key findings by Anderson and Seltzer, see this incident table.

^^They were less worried about their responses ending up 8 decades later on a historian’s desk, or (more likely) had never considered the possibility. It was literally inconceivable that those responses might show up on a historian’s blog!