Refusals and Redlines

Herbert Mace did not want to be seen. He also really wanted everyone to see him not being seen. I began this essay anticipating a story of local resistance and grand politics, another small piece of the roiling controversy that surrounded the census questions of 1940. But as so often happens in these Census Stories, the more I dug into Mace’s story, the more other characters captured my attention and stimulated my imagination. Their adventures seemed superficially more mundane, but on reflection grew in significance. The really exciting stuff can sit right next to the controversy. That’s the case with Mary Brown Bryant, who was a housewife, a sometimes single parent, an agent of American commercial empire, an “unladylike” census taker, and a participant in contentious efforts to inventory Americans’ houses.

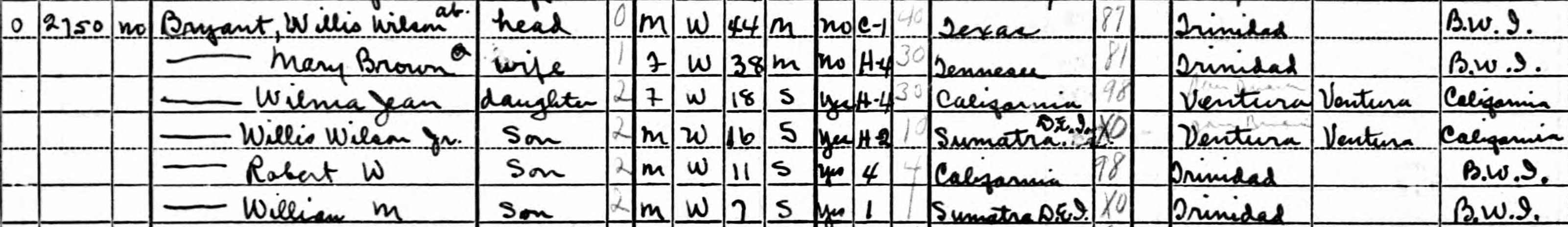

Below is an image of nearly all we know about Mary Brown Bryant and her family in 1940. The census recorded so few pieces of a life. Still, I can’t help glimpsing in them a plausible story. ^

Mary’s husband, Willis Wilson, wasn’t at home in April of that year. The census recorded his occupation as “contractor” in the “oil industry” and it seems likely he was abroad. Born in Texas, Willis may have grown up in the oil fields, but at some point his work sent him much farther afield. Five years earlier, the Bryants had lived in Trinidad, in the British West Indies–a sojourn that split their family. The two older children, Wilma Jean and Willis Wilson Jr., stayed in California (for school, one imagines) while little Robert and William traveled with their parents. The Bryants seem to have spent even more time half-way round the world in the East Indies before that. In the mid-1920s, Mary gave birth to Willis Wilson Jr. in Sumatra, then under Dutch control, and seven years later brought William into the world there too.^^ That Robert was born in California four years after Willis and before William suggests a life of backs and forths, of Bryants chasing the barrels of oil that America shipped across the world in this very globalized age before so-called globalization.^^^

The census taker found Bryant at home on April 9 and she answered the questions for her entire family. One week later, with Willis away, Mary struck out on her own, perhaps with a child or two in tow, to survey the neighboring community of Artesia and its rural surrounds. This time she would ask the questions.

Two days into her period of service. On April 18, Mary Brown Bryant moved systematically, door to door, down West 6th street, just outside Artesia in Los Angeles. She passed the dairies that stretched west of Pioneer Boulevard and enumerated sundry “hands,” “milkers,” and “operators” who worked the land and looked after the cows.

She should have also encountered a former preacher at 306 W 6th, immediately after counting two Dutch families responsible for one such dairy. But she did not. Herbert Mace did not want to cooperate. In fact, he chose to be uncooperative in an ostentatious fashion.

The records with Bryant’s account of what happened have not survived, so far as I can tell. That leaves us to rely on Mace’s account, and he was an unreliable narrator.

In a letter to New Hampshire Senator Charles W. Tobey, whose crusade against the census’s economic questions drew Mace’s attention, Mace claimed that Bryant first found him on April 17. After that Mace—who was violating a federal statute by evading Bryant—says he went to the US District Attorney to file a complaint against Bryant. He went looking for trouble.

To ensure that the whole world could witness his protest, Mace wrote The Los Angeles Times on 25 April: “Yesterday a census taker called at my home, demanding answers to certain questions that I consider my own private affair.” Mace referred to the enumerator using masculine pronouns in this this initial letter.

She became a woman again in later tellings, when her gender became a part of the offense. “I felt the actions of the census taker very unladylike;” wrote Mace to a San Diego paper.” When the Census Bureau demanded that Mace write Bryant and supply his census answers, he “stated that I did not consider a woman a lady who would come into a man’s home and demand with a threat of injury private information; that therefore I did not care to have any correspondence with her…”

It’s impossible to know if Bryant considered herself a lady. When she answered questions about about herself, Bryant answered “no” when asked if she worked in March of 1940. The enumerator’s “H” a few columns later indicated that Bryant had been “engaged in housework.”

Nearly half of all enumerators were women. A quarter (26%) were “housewives,” according to an analysis from the bureau–a group just barely eclipsed by “salespeople and clerks.” I’ve mentioned this before, while discussing the enormous (forgotten, hidden) contribution of Elbertie Foudray and other census women. Bryant’s story helps illuminate some of the particular challenges such ordinary women may have faced when they ventured to strangers’ homes to ask dozens of questions, some of which had stirred up a national controversy.

Mace made the matter personal. He did not just object to the census questions. He lashed out at the census’ local agent. Those who fought the census often focused their disdain on the bureau’s local representative. Letters protesting the census drip with bile when they describe the census taker. Harold J. Stewart of Portsmouth, NH, for instance, condemned his enumerator for being one of “the notorious local Democratic ward-heelers and so crooked he cannot even lie straight in bed.”

In an earlier incident, a Kenosha, Wisconsin man grappled with an enumerator for the business census. James Rosselli owned three shoe repair shops and looked every bit the cobbler, with his massive arms, wide frame, and striped apron. Without fail, reporters listed him at 250 pounds, as if they were discussing a prize fighter instead of a disobedient citizen. He too made it personal. “We grabbed each other by the coats,” as the confrontation escalated. But Rosselli insisted: “I would have answered questions if he had asked them politely.” Much to the chagrin of the Census Bureau, who did not need any bad publicity in March on the eve of the population count, the enumerator and his supervisor brought charges against Rosselli. The bureau insisted they be dropped and sent the area supervisor Donald Ferris to try the enumeration again. Rosselli answered the question, declaring Ferris “a gentleman.”

The census forms asked about sex, and the only options for any individual were M or F, male or female. Yet whenever a census taker encountered another American, the two spoke in a room crowded by gender expectations. And if anything went awry, the trouble often came to be understood as a failure to live up to those expectations. And so Mary Brown Bryant became “unladylike.”

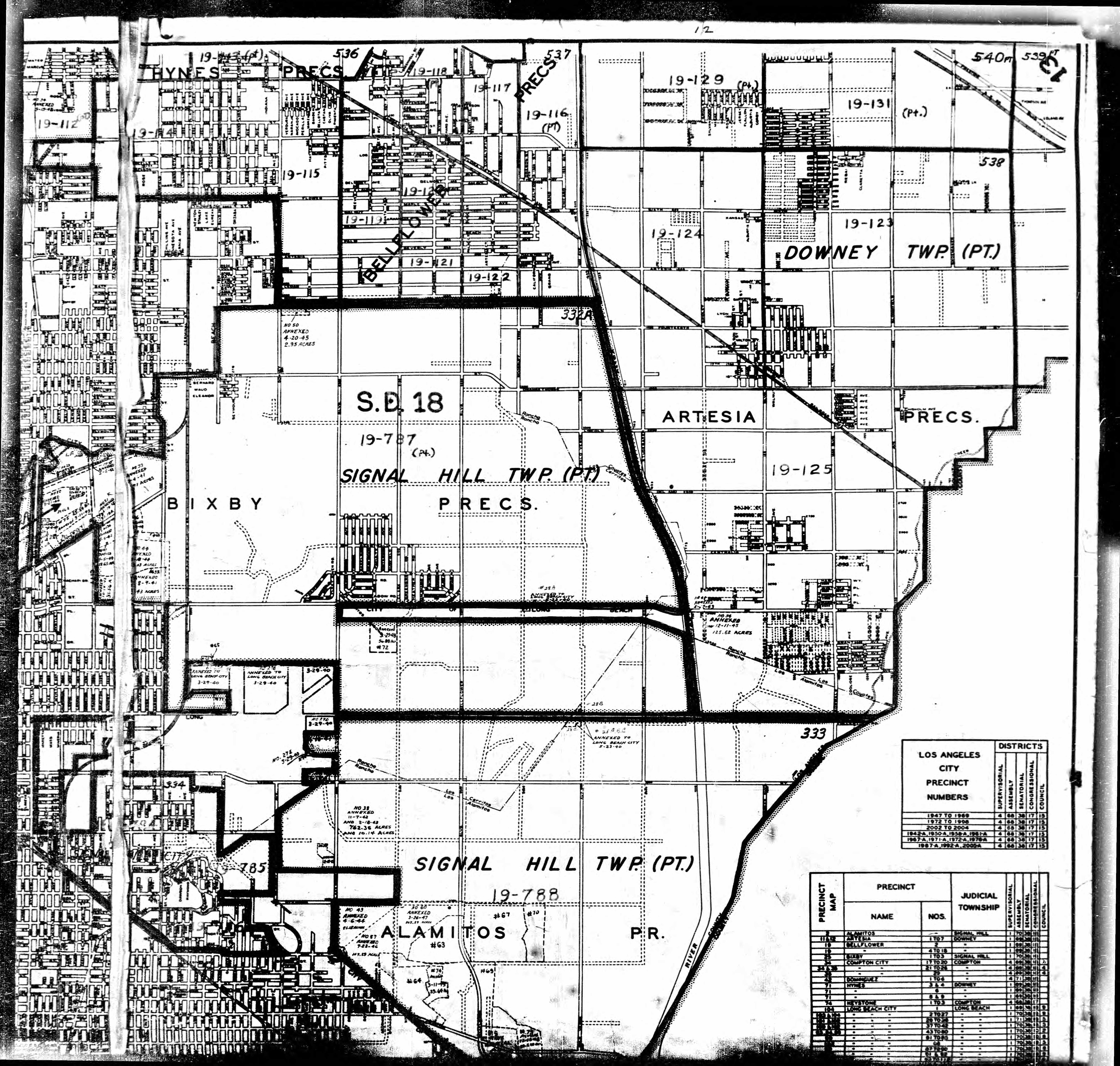

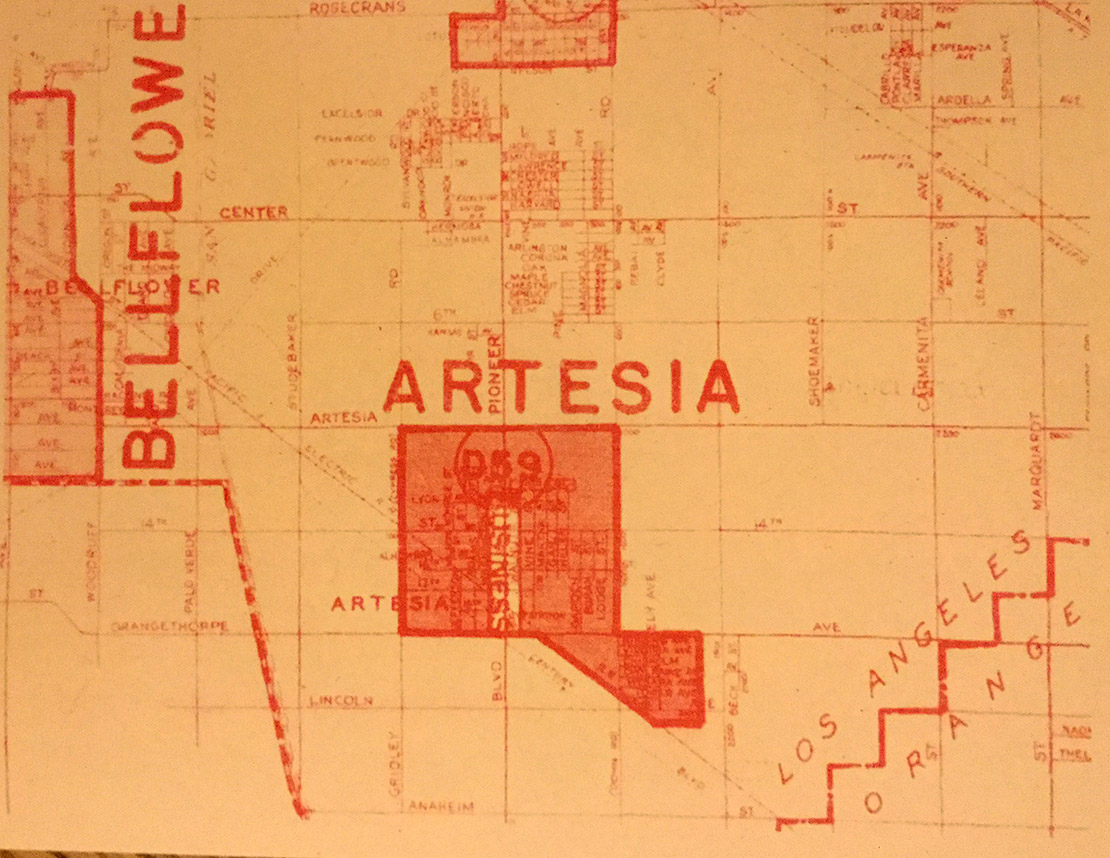

To work out Mary Brown Bryant’s path, I turned to one of the maps that would have been available to her: a map from the Bureau marking off each distinct census district. You can pick out the stamp indicating Bryant’s district, 19-124, in the upper right quadrant, to the left a bit of the label for Downey Township. But other details are harder to glean from this copy of the map. The outlines of the districts are darker (and so clearer) on the left/east side than on Bryant’s side. The San Gabriel river bounds 19-124 on the east, Center Street to the north, Pioneer Boulevard to the west, and Orangethorpe Ave to the south. The Pacific Electric Railroad cuts through the district, a reminder of when LA used to be a city of trains as much as cars. On this map, I mistook the diagonal railroad line for a district boundary for quite some time. It’s a hard map to read.

At that point, I turned to Google. But good luck finding a 306 W. 6th Street in Artesia, California! In the nearly eighty years since Mary Bryant Brown bounced off Herbert Mace, Los Angeles has churned and grown, destroyed itself and rebuilt itself over and over. Satellite images catch the railroad’s ghost still haunting the landscape, but much else has changed.

6th Street is now 166 and where cows once munched lawn mowers now bite, pushed by legions of suburban teenagers. Google could not help.

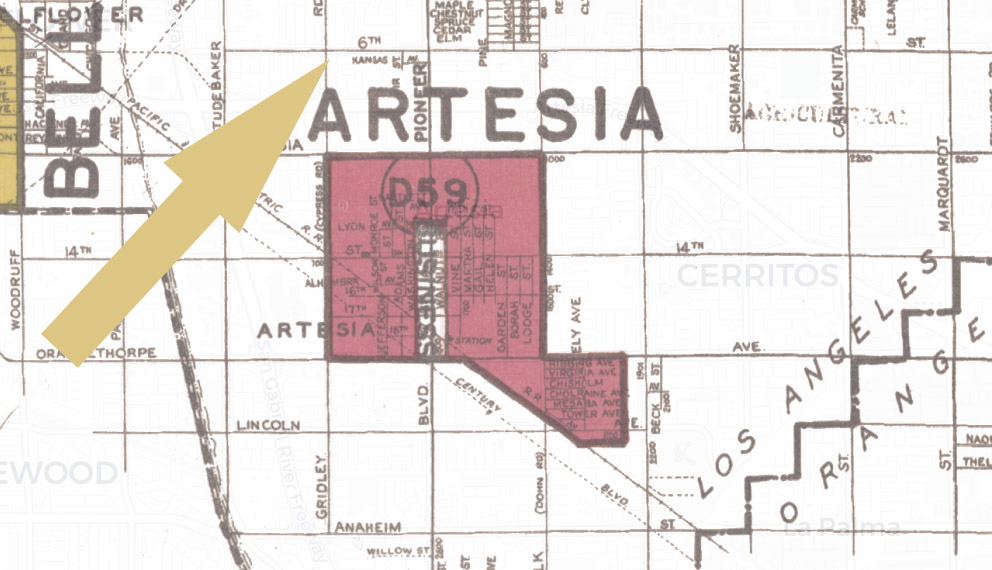

Where, I mused, could I find a precise, accurate map of a United States city around 1940? HOLC, I realized: the Home Owners Loan Corporation! Thanks to an ambitious and elegant project by scholars from the University of Richmond, University of Maryland, Virginia Tech, and Johns Hopkins, one can view a vast collection of HOLC maps for US urban areas online at Mapping Inequality.

Sure enough, I found an excellent and legible map of Artesia there.

Complete with 6th Street, in all its vague, ruminant-trampled glory.

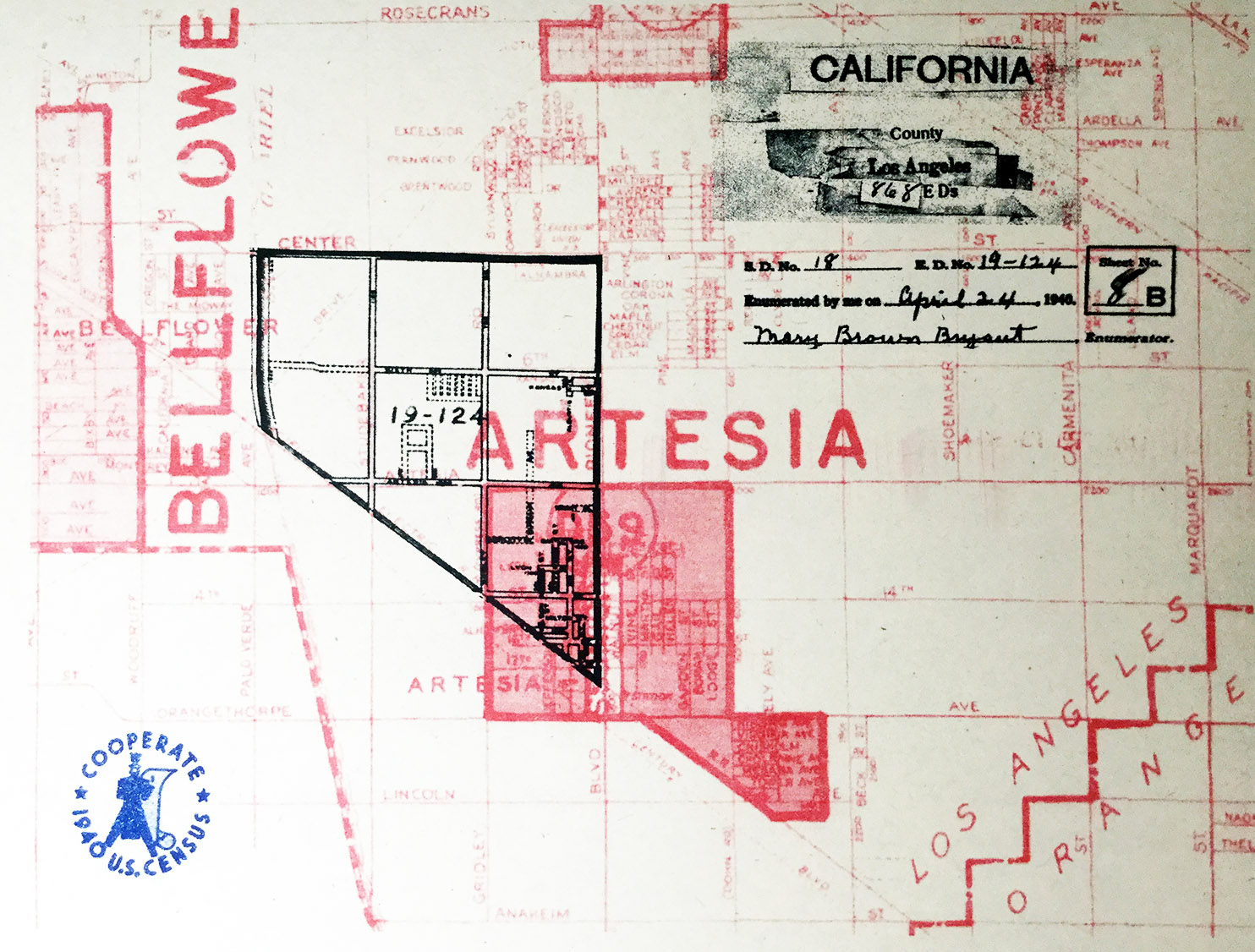

Of course, there’s another thing that stands out on this map: the red stain covering much of Artesia. This was a “redlined” area, one deemed exceptionally risky by the local appraisers, realtors, or mortgage lenders who fed information to HOLC (which was part private enterprise, part public office). Living in a redlined area meant one paid dearly for credit to purchase one’s home, if one could get such credit at all. HOLC still lent money in areas like Artesia, but its classifications perpetuated and made official discriminatory judgments that had probably already disadvantaged Artesia and its residents for years.^^^^

In 1939, HOLC informants looked at Artesia and saw an ill-organized, defunct city with no future and distressing (to their eyes) concentrations of Mexicans and Japanese. Artesia had schools and churches, and even a handy railroad stop. This was all good. But the sewers didn’t extend as far as they might, much construction was “substandard,” and not all land had been improved. “The area is practically dormant,” argued the surveyors. The biggest problem, though, seems to have been the fact of “slight concentrations of Mexican families and some Japanese in the southwest section with many more residing in the countryside round about whose children attend the local schools.” The next line reads: “The area can only be accorded a ‘high red’ grade.”

A year later, Bryant covered some of the same ground: all of the ground west of Pioneer Boulevard, which cuts the redlined square in two and extends past it into the open, un-marked lower density areas. Walking outside town, on just her first day–and two days before Mace started causing trouble–Bryant encountered Dutch dairy farmers, a railroad mechanic from Iowa, a Kansas-born oil man, a Mexican “Log Ranch” manager with his Arkansas-born foreman, and a Japan-born couple who ran a small vegetable and fruit (“truck”) farm with the help of their California-born nephew (named Jack!). Dutch dairy farmers, Japanese truck farmers, and Iowa-born hands cover the ensuing pages. Each brimming with narrative possibility: like Shigeki Yokoyama, the 42-year-old high-school educated farmer born in the American territory of Honolulu (and so a citizen), his Japanese wife Satoyo, who had no formal education but helped on the farm, their three California-born children, and Shigeki’s Japanese mother Kumi, who kept up house that the family owned.

Around April 25 or 26, Bryant entered the redlined area, although the way her path crossed in and out of that square reminds us that it was a bureaucratic designation and not a real barrier or impediment. Bryant never stepped over any redline and crossed the divide freely. Nor did crossing the line herald disaster. If anything, Bryant found many more people born in the United States, many more individuals who owned houses valued in the low thousands of dollars, and a different class of workers: more skilled artisans, professionals, and oil or construction workers. Here too, intriguing characters abound. Like Anne Dobias, the widowed Czech “janitress” for the local library who lived with her four children (all born in Maryland, and including a bank janitor, an ice plant machinist and a “telephone messenger”) and owned a simple house worth $1,000. Or Lucille and Jim Azevedo of the Azores and their five California-born children, who worked on dairy farms, and were one of a many migrants from the Azores who for some reason landed in Artesia.^^^^^

Bryant completed her rounds on May 4, criss-crossing town to gather those few households that had so far eluded her. I cannot say if she ever met Herbert Mace in person again. But he did submit his data, by mail on July 31, after serving time (and catching a cold) in jail. The Los Angeles Times published his photo. Mace’s blonde, thick, wavy hair crowned dark eyes and a closely trimmed beard and mustache (or perhaps a jail-grown stubble). A handsome man in a collared shirt, he held a fountain pen in his right hand, with which he surrendered his data. The paper half-mourned, half-mocked Mace’s adventure: “He was no longer a rugged individualist, he was going back in the great American mold.” Mary Brown Bryant, however, never warranted a photo, or a mention.

The stories of Bryant, Mace, and Artesia’s HOLC maps are all stories about housing, and for that reason of momentous significance.

While many of his contemporaries protested admitting their wage incomes most vociferously, Mace singled out housing data as particularly sensitive. “As to whether a man pays $5 or $100 a month rent is a matter of little importance; it makes little difference whether a man owns or rents.” What mattered, he insisted was “that government is intruding on the rights of the people and the people in defense of justice and liberty should refuse to answer such personal questions.” The government had no right to meddle with Mace’s housing finances.

Weldon F. Heald of nearby Altadena disagreed. In a letter to the editor the following week, Heald wrote: “Mr. Mace, as far as the census is concerned, is a digit who is arrogating to himself a personality out of place in statistics.” He continued, “Nobody cares whether Mr. Mace owns his house or not, as an individual, but it is of the utmost importance to find out whether 5 per cent or 20 per cent of our population are house owners.”

Heald seems to have been a wealthy man himself. He owned a house worth $20,000 according to his census record. He managed, for his part, to keep from his enumerator any information about his occupation or income though. Heald too may have been a digit with some personality.

He had a point, though. Mace got much more direct attention by not talking to his enumerator than he would have otherwise. To the census he was a digit, a building block in the project of learning to see and understand America’s housing just as the federal government got into the business of encouraging home-owning and suburbanization and as housing became an engine of the soon-to-be booming American economy. As the introduction to Mapping Inequality puts it: “More than a half-century of research has shown housing to be for the twentieth century what slavery was to the antebellum period, namely the broad foundation of both American prosperity and racial inequality.”

Thanks to Robin Sloan and my all-too-brief residency at the Murray Street Media Lab, I can sum up this multi-layered story visually.

On Robin’s risograph, we (which is to say Robin, while I watched) printed our HOLC map in red, for obvious reasons. It, like housing and redlining, is the foundation.

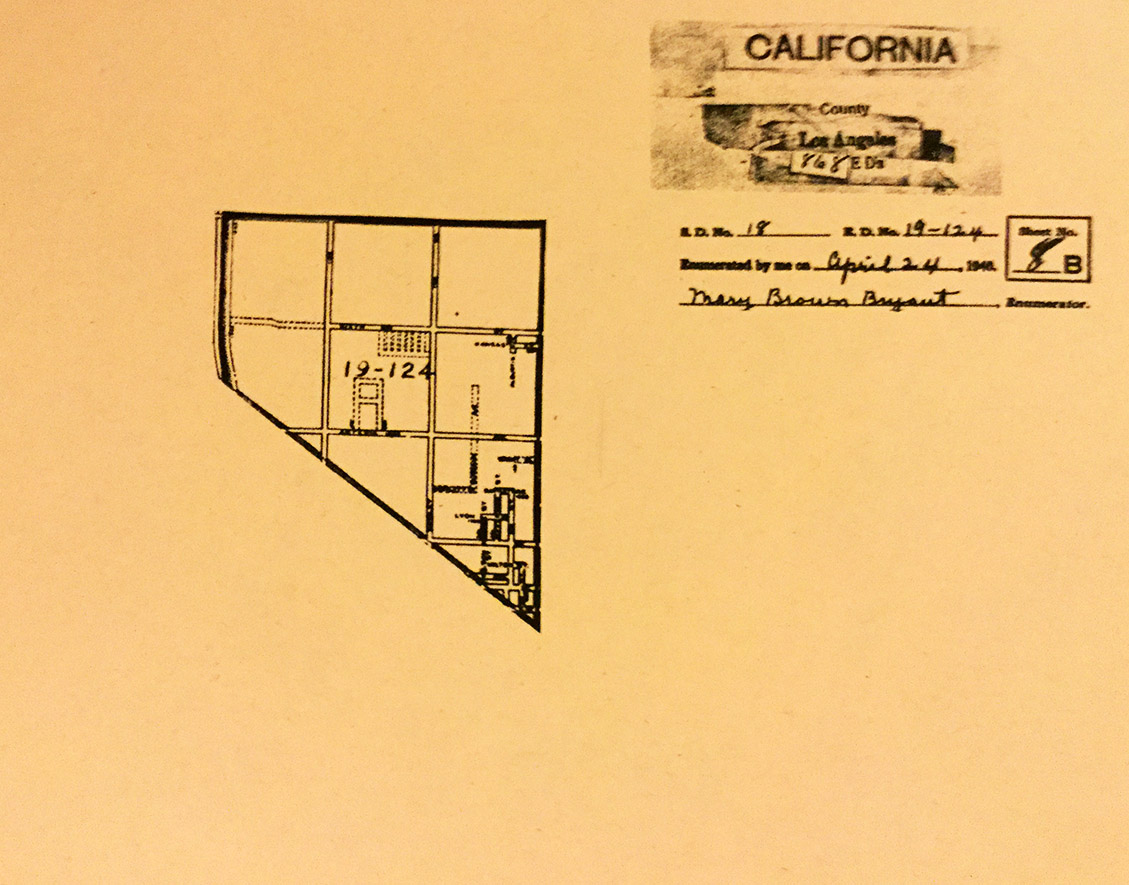

On top of that we printed the north half of Bryant’s census tract in black, like the black and white facts she was supposed to be collecting in her “unladylike” way. Here it is printed alone, for clarity.

To top it all off, we added the official 1940 census stamp in blue. So, here’s the conclusion to this census story:

Cooperate!

^Of course, this story is probably wrong. People sometimes lied to the enumerators, withheld information, or struggled to fit complex circumstances into a narrow form, and enumerators made assumptions or drew false conclusions from the evidence of before their eyes. I think it contains a kernel of truth though.

^^It’s possible that these children were born to someone other than Mary. Indeed, I thought that might even be likely given the 5 year gap between Willis Wilson and Robert, and the fact that Wilma and Willis stayed in Ventura five years earlier. However the fact that both Willis and William were born in Sumatra argues for more continuity. We cannot tell for sure.

^^^One of the founders of the discipline of American Studies, Perry Miller, also followed American oil around the world. In the preface to his classic Errand in the Wilderness, Miller wrote his time in the merchant marine and the “epiphany” that struck him as he watched his peers unloading barrels of American oil at Matadi on the Congo River, presumably to grease the wheels of the Belgian colonial operation. Styling himself a Gibbon for a waxing empire, he wrote: “It was given to me, equally disconsolate on the edge of a jungle in central Africa, to have thrust upon me the mission of expounding what I took to be the innermost propulsion of the United States, while supervising, in that barbaric tropic, the unloading of drums of case oil flowing out of the inexhaustible wilderness of America.” (viii)

^^^^I use “redlined” a bit loosely as a term here. To prove Artesia was actually redlined, I’d need evidence that Artesians secured loans at unfavorable rates or could not get loans because of racism. My data doesn’t cover mortgage information at all. And As Amy Hillier has shown, being red-shaded by HOLC did not mean HOLC or other lenders would not provide loans. Rather, the HOLC shading offers us evidence that local experts deemed an area risky, a set of judgments that shaped local lending patterns and influenced the distribution of federally supported mortgages through the FHA—such that neighborhoods the FHA graded “D” were, essentially, doomed to physical decay.

^^^^^The Dutch dominated the local dairy scene, but Manuel and Rita Silva assured that the Azores-crowd had a representative in that key local industry too.