Abnormal Conditions

The scientists in the census office wanted to purify the nation’s statistical infrastructure. The 1920 census provided them another opportunity to advance that cause. Having won a permanent office furnished by a core of experts and professionals, they turned their attention to rooting out fraud—and politics too. The fixation on fraud, and abnormalities that fraud might introduce into the record, blinded them to a graver danger threatening their census, their authority, and their data.

On 3 July 1917, the Census Bureau’s director Sam Rogers named Dr. Joseph A. Hill to an internal committee that would prepare for Congress a report and sample legislation to govern the Fourteenth Decennial Census, which would take place in 1920. That committee’s chair was the Chief Statistician for Agriculture, a Mississippian named William Lane Austin who had climbed the census ranks from his early days counting cotton. The other members included the Geographer who would be responsible for breaking the nation into enumeration districts and preparing maps for enumerators, the Chief Statistician for population, and William Steuart, a census expert temporarily on loan to the U.S. Tariff Commission for war-time work. Over the course of six months they held 19 meetings to determine what to keep from the legislation that governed the 1910 census and what needed to be changed.

They focused on fighting fraud. They appear haunted by what had happened in Tacoma, Washington in 1910. The initial reports from the census field force credited more than 116,000 residents to Tacoma. But when the Bureau started digging it found that number to be massively inflated—by over 30,000 false or fictional entries in the census schedules. Enumerators had essentially invented about a quarter of the city’s population. Enumerators had personal incentives to inflate the returns, since they were paid per person they enumerated, and the cities they counted were only too happy to have their populations (and so representation and status) artificially increased. Hill and his colleagues determined to prevent such a thing from happening again.

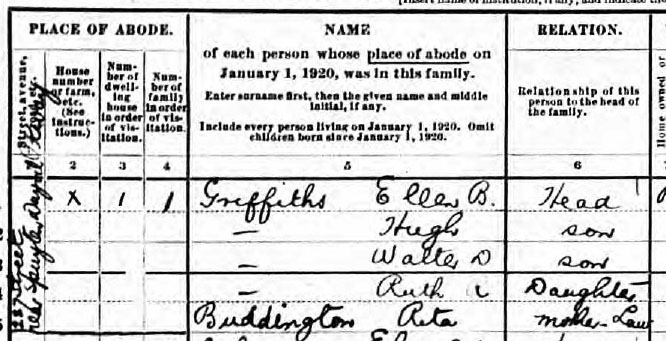

The strangest things had to be regulated to prevent fraud. For instance, the committee recommended changing the census law to include “place of abode” in the list of things to be enumerated. That was far from revolutionary—the census had always been concerned with putting people in their physical places—but the formal legislation in 1910 had not included the requirement and that had mucked up the effort to punish Tacoma’s enumerators. As W.C. Hunt, the Chief Statistician for Population, explained it to Hill: “in the prosecution of the Tacoma enumerators in 1910, the point was made that that the law did not require the enumerators to return the residence and, therefore, their failure to denote the residence in any case did not indicate fraudulent intention on their part.” The committee was writing the law to make it easier in the near future to prosecute their own statistical workers in the field.

The census column following “place of abode” and “name” also owed its existence in 1920 to fears of fraud. Trying to save space on the schedule, the internal committee had voted to remove “Relation” from the form. But Chief Statistician Hunt fought for its inclusion on the grounds that it served as a “deterrent” against any “padding” of the population by fabulating enumerators. He reasoned that it would harder for enumerators to make up not just names, but also whole familial and household structures. Further, he argued that the relationship information could help sniff out fakes later in the process. The Bureau could look for an excess of individuals outside households, or any odd collections of very large families, or a profusion of “boarders” or “lodgers.” He did not say that this method of data surveillance would also render suspect large immigrant families or individuals in poorer or immigrant communities, who tended to make rent by subletting rooms. In the end, Hunt’s argument helped get the “Relation” category back onto the census schedule in 1920. To fight fraud, the bureau needed to decide on its own what “normal” data looked like, and build a system that would reveal the abnormal.

When a committee of the House of Representatives held hearings to work through the census proposals, the bureau’s leaders stuck to their priorities. On 20 February 1918, the first day of the hearings, William Steuart told Congress: “I think the real important changes or amendments that have been made in this law relate to the machinery that the bureau will put in force to prosecute fraudulent returns and fraudulent answers on the part of the enumerators or other employees.” (45) The new law would prevent a recurrence of the Tacoma fiasco.

There was another thing that Steuart emphasized too: raising the salaries of census scientific staff and office clerks. Census officials were not only haunted by the frauds of 1910, but also by their office’s failure to process, tabulate, and print the census within the three-year period prescribed by law. The new bill pumped resources into the census office so that it could hire and retain better workers to handle the adding and sorting machines, prepare statistical tables, and write final reports. All that money directed toward the scientific staff also advanced the agenda of the scientists themselves. They could increase their own ranks, and exert more control over the rest of the process.

Bureau scientists sought more control of the entire enumeration. It was one thing to be able to prosecute fraud committed by rogue enumerators, but another entirely to prevent enumerators from going rogue in the first place. Hill and his committee appear to have believed the problem lay in the nature of the men selected. Enumerators in prior counts had been chosen by supervisors who where themselves chosen by the President from a list prepared by the Senate and House. To one member of Congress, this process seemed to assure that “men of well-known efficiency and character have been chosen as enumerators.” Census officials instead saw the twinned and twined perversions of patronage and politics. Hill’s committee called for all hiring to be directed by the Secretary of Commerce, which (they hoped) meant that it would be directed by them. Notably, Hill and his associates did not ask that enumerators be paid more. They asked for better wages to attract office workers to Washington, but did not think they needed to pay better wages to get a better field force. They just needed to purge that force of its partisan, political influences.

The way census officials wrung their hands about out-of-control enumerators did not square easily with their confidence that, in the words of the Secretary of Commerce: “the census work is to-day the most accurate census work in the world.” A day earlier, the Secretary of Agriculture had guessed the U.S. census was “best in the world, I imagine.” During one hearing a House member aired rumors of widespread error. He said: “Ocassionally we hear a statement to the effect that the statistics in the bureau are not accurate and that they are at best an approximation. It is attributed to the type of enumerators selected in gathering the work.” He asked:”I want to know whether that criticism is justified or not?” Put on the spot, Chief Statistician Hunt defended the enumerators and their numbers. “We consider it [the census] is within 1 per cent of the facts” or “within 1 per cent of accuracy,” the Chief Statistician explained. That one percent figure probably referred to a calculation made by Walter Willcox in 1897. There’s no reason to think that Hunt testified to Congress disingenuously. Rather, the preparations for the 1920 census make clear that, in the eyes of those would ran the count, it was startlingly accurate and at the same time in need of significant reform.

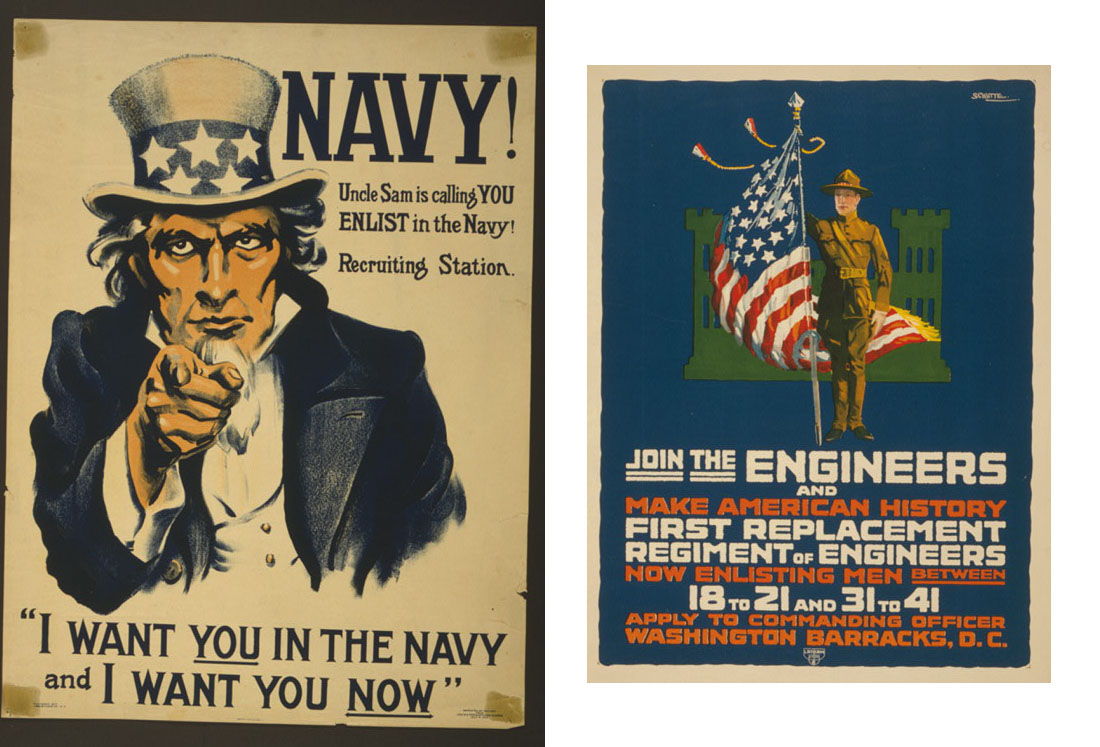

In April 1917, just before the Census Bureau began making plans for 1920, the United States declared war against Germany. The following month, the Selective Service Act became law requiring the registration of all male citizens between the ages of 21 and 30. First came registration, then the draft for war. In the meantime, the government actively recruited volunteers, with posters like these:

(Posters from the Library of Congress, here and here.)

The Selective Service system registered 24 million men by the time the war was over. The first draft in 1917 sent 687,000 men into the army. About 4.8 million men eventually served in the military during the war. The Provost Marshal General Enoch H. Crowder, who ran the registration, suggested that its methods could be used for the 1920 census.

They weren’t. But Congress did have its doubts about the wisdom of conducting a census by ordinary means in an ordinary way. These were, after all, extraordinary times.

The members of Congress holding hearings on the census did not seem all that concerned about fraud. They were absolutely obsessed with normality. Actually, they were obsessed with its absence.

Harvey Helm, a representative from Kentucky (D) and chairman of the House Committee on the Census, listened more-or-less patiently to the Census Bureau report and then asked a question that really only had one answer: “Will this census that will be taken, assuming that the war continues, be a normal census?” Helm initially had in mind that the data on business and manufacturing might be particularly abnormal, and the Director of the Census agreed with him. But as the hearings progressed, the assumption of abnormality came to envelop the entire census.

Everyone agreed that some sort of census was necessary: the Constitution demanded a head-count, at the very least, to take place in 1920. But that did not mean Congress needed to authorize a complete census, one that would inquire into various ancillary facts about individuals, and also gather facts about the nation’s mines and forests, its factories, farms, and shops. Hearing after hearing, a new government official came to testify—one day the Secretary of Agriculture, another day the Chief Statistician of the Food Administration, another day the Director of the Geological Survey—and Harvey Helm or one of his House colleagues asked some variation of the question: will it do any good to do a full census if we’re still in the middle of a war?

The Congressional Committee debated the wisdom of funding a full census in uncertain times. In these hearings, members debated a census in “disturbed” conditions, of a “disorganized” nation, of a society in “upheaval.” But more often than not, they beat the drum for “abnormal,” over and over, time and again. Everyone seemed to agree that this would not be a normal census.

They failed to agree on the implications of that abnormality. For some, a census in abnormal times was by definition a waste. But census officials responded that the greater waste would come from mobilizing nearly 100,000 enumerators to make the count and then limiting the scope of their investigation. Since the Constitution required a population count, and that count required census takers, why not go whole hog?

Some argued that the abnormality of the times would make the census even more valuable. How else, they said, would policy makers know how to fix the nation, or when it was back in shape? As Louis Fairfield, a representative from Indiana (who was, of course, born in a log cabin), put it:

It seems to me that while conditions, of course, are not normal yet, when a man’s business is disorganized it would seem that the more thoroughly he understands the character and extent of the disorganization, the more easily he can take effective means to remedy that. I may be wrong, of course, but it looks to me that at no time in our history would it be more advantageous to have a full knowledge of the conditions that obtain at this particular time, for the readjustment which must come, in regard to the derangement which has been caused.

Maine’s Ira Hersey countered, asking “what benefit will information as to abnormal conditions be to a person in normal times” and answering his own question: “a matter of history, that is all.” But, then, is history so bad?

Representative Niels Juul of Illinois argued for the census this way: “I should like to ask you how are we going to find out in the future that we have again arrived at a normal condition if we have not the statistical information of the abnormal conditions as they exist during the war?” The census became a kind of baseline for abnormality, a measure of our distance from normal.

But what if there was no normal to get back to? The Secretary of Commerce William Redfield looked at what was happening in America, at the changes being wrought in its society and its industries, and he saw a “revolution.” He told the Congressional committee: “If anybody had told you or me five years ago of what we see in this country now we should have thought him insane.” The census that would go out in 1920 would capture a record of a “new world.” At that point, Redfield turned Biblical:

and I can not put it better than the expression in the Old Book, that former things have passed away and all things have become new, and the data of the past is historically interesting, but that is about all.

Redfield proclaimed a new beginning for America, including for its data.

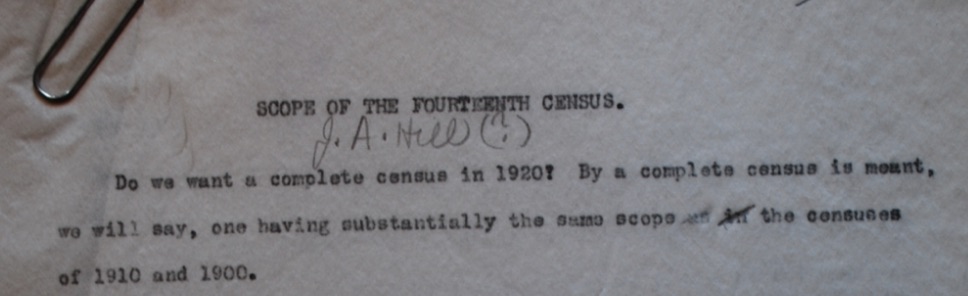

There is an undated manuscript in Joseph Hill’s files in the National Archives. In it, we see how Hill tried to work out the implications of abnormality.

Hill was defensive. He felt the need to justify the approach that he and his colleagues had taken. “I would like to say that we fully recognized that the census of 1920 would be taken under very abnormal conditions,” he wrote. But the Constitution required an enumeration, and they could not tell in 1917, nor could they tell whenever he wrote this memo, if the war would in fact be over by the time the census began in January 1920. “We may have peace before that time,” he wrote, “or the war may continue.”

In the surrounding pages, Hill admitted the abnormality of the times. Indeed, he wrote, that were it not for the Constitution, “I think there would have been a practically unanimous opinion within this Bureau, as well as outside, that the census should be postponed for a year or two, say until 1922.” He said this after rehearsing the argument that “deferring a census until times are normal is like refusing to take the patient’s temperature until we are sure that his fever has subsided.” In this document, Hill worked out in his own mind how the Bureau could limit the number of questions asked in 1920 and only ask the most useful, the most likely to yield good information.

Data on people’s occupations struck Hill as that which would be most perverted and ultimately useless. “Abnormal conditions largely destroy the value of [occupation] data,” he wrote. “The present conditions are too disturbed and too transitory.” Other questions, through, had been made much more important by the war. On the question of “navity” he wrote: “I believe that the composition of our population as regards race nativity or nationality is, if possible, of greater interest and importance at this time than ever before.” Similarly, the question of “mother tongue” would be necessary to determine the “accurate racial classification of our white population of foreign birth or foreign parentage.” And then there was the citizenship question, about which Hill exclaimed: “There never was a time probably when it was more important than it is now to know the number of aliens in the United States and their nationality or race, also the extent to which the foreign born have taken out naturalization papers.” Hill was right in calling out the future importance of such data. In the coming decade, nativist forces would push through a series of draconian immigration bills, justifying their actions with census data, and ultimately using that data to set very strict quotas.

The silver lining of curtailing the census in 1920, for Hill, was that it opened the possibility of another census five years later. He wrote, “In view of the abnormal conditions now confronting us we might think it best to take a limited population census in 1920 and the complete census in 1925.” This was not a new idea, exactly, Hill and his colleagues already wanted a quinquennial population census. Hill embraced abnormality to see if it would get him, and the Census Bureau, more data.

“But could Congress be persuaded to do that?” Hill asked. Ah, Joseph Hill would soon be surprised (and not pleasantly) by what Congress was willing to do.

This post is published under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license by me.