Paths to 87 Hamilton Place

At 87 Hamilton Place in New York’s Harlem neighborhood, just blocks away from City College, Lucile Kenn encountered and enumerated glimpses into a transnational nation, a nation of nations. In one apartment she sketched out the statistical life of the Hungarian-born artist Lily Furedi, whose portraits of American life I’ve already discussed. Furedi represented a by-then-fading mode of migration, a person or family moving from the “Old World” to the “New.” Immigration restriction laws passed in 1924 had been designed precisely to keep out people like Furedi and the few Bulgarians and Russians in the building. Three doors down from the Furedis, Kenn interviewed a family who migrated by a different route, who had followed paths worn clear by the ships of American empire: Mercedes Hizcarondo married to Manuel, both from Puerto Rico, and their son, another Manuel, born a New Yorker.

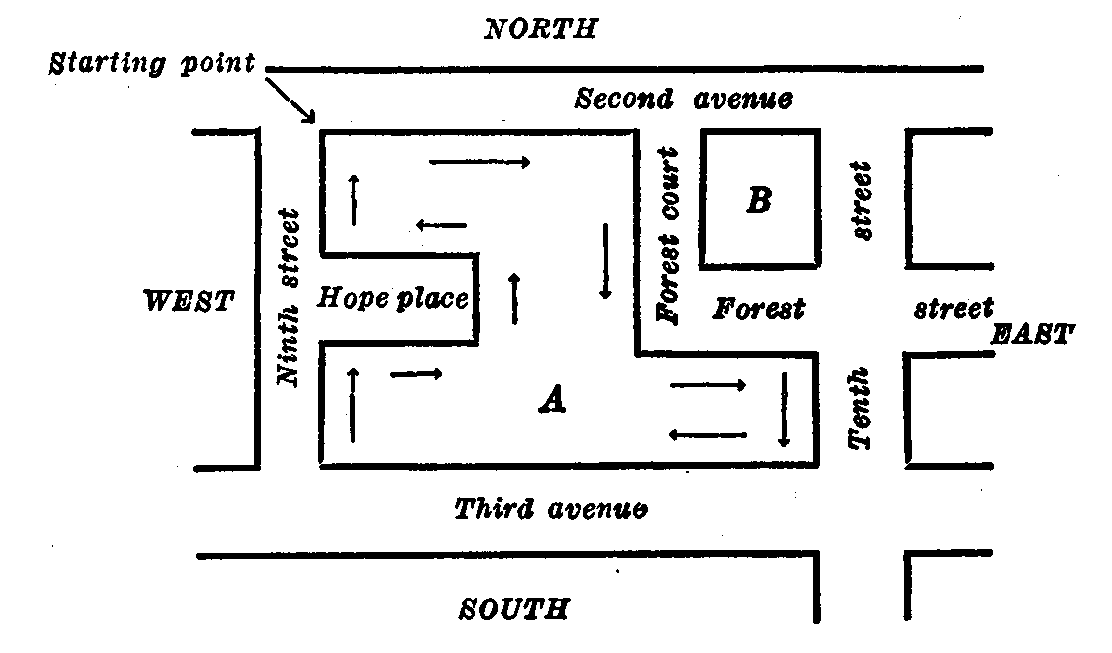

I traced Kenn’s own path to the door of 87 Hamilton Place. Her enumeration district spanned only two small blocks, but these were apartment blocks. The Census Bureau’s schematic diagrams flattened vertical space as they instructed census takers in the proper method for covering their routes to ensure a complete count:

Here is a map of Kenn’s district, 31-1829. I overlaid the relevant snippet of the original 1940 enumeration map on a Google satellite image:

But these buildings climbed into the heavens. And they crammed in residents. 87 Hamilton place held 46 households and 221 individuals. Had it been about twice that size—100 apartments—the building would have counted as an enumeration district all by itself.

The building at that address today looks like this: (I’m still working to find out if it’s the same one. But I suspect it is.)

87 Hamilton Place marked the end of Kenn’s census journey. She began her enumeration there toward the end of 13 April 1940. For 4 days she worked her way through the U-shaped halls. Census officials did not instruct enumerators on how to approach an apartment building systematically. Did Kenn start at the ground floor, or climb to the top and work down? There’s no way to know. What we do know is that her first interview of the day took place with Ernest Foring, a 51-year-old with his wife, two sons, and a lodger. Foring gave his occupation as “Janitor,” working for an “Apartment House.” It seems likely he looked after 87 Hamilton itself.

Foring was born in Germany, like 9 of the other building residents. Kenn was born in New York—like 46 of those she interviewed at 87 Hamilton Place. Kenn counted 27 people born in “Eirie,” as she recorded it—Irish-born—and distinct from the 3 building residents from “No. Ireland.” Such were the traces of the streams of migration that throughout the nineteenth century had largely defined New York and large portions of the United States.

Puerto Rican residents (born in “Porto Rico” as Kenn wrote it using a common spelling for the time) numbered 77 in all, more than the Irish- and New York-born combined. The building also housed individuals from Santo Domingo, Haiti, Chile, Cuba, Venezuela, Mexico, Spain, Canada, and India as well as from a handful of states in the U.S. But most numerous by far were Puerto Ricans, many living in their own apartments while others roomed as lodgers.^

Kenn’s census ledger^^ offers us glimpses into these 77 lives:

Emma de Thomas lived as a lodger in Antonio Rubio’s (Colombian) and Delores Rubio’s (Puerto Rican) household. She was 23 years old and a recent migrant. Just five years earlier she lived in Yabucoa. Now she worked a factory job. So did her host Delores, while Antonio waited tables.

Lisa Montalvo, 37, worked as a maid in Vincent Bolta’s apartment, where she also lived. Her 15-year-old daughter Lillian helped out. Bolta supported his household as a clerk specializing in “machinery.” (Census records can be either maddeningly vague or delightfully suggestive! It depends on your sensibilities.)

Richard Rodriguez, 53 years old, from Spain, repaired meters for the electric company. He also seems to have run a little hotel out of his apartment. Listed among his lodgers are the Gonzalez family of three (Caesar born in Florida, Carmen in Puerto Rico, and little Caesar in New York), the Jaimes (Concepcion cut hair in a barbershop, supporting Parquita, both hailed from Puerto Rico), Joseph Leego (a single “presser” at a cosmetics factory, born in Puerto Rico), the Grajalas (one an assistant chemical engineer at a soap factory, both from Puerto Rico), and Maria Lizardi who packed dry goods at a warehouse, having arrived within the last five years from San Juan.

The Montalvos, Grajalas, and Gonzalezes—as well as Maria Lizardi and Emma de Thomas—undoubtedly each had their own reasons for moving to New York. But the paths they trod together to 87 Hamilton had been laid by the U.S. invasion of Puerto Rico in 1898. ( I discussed the subsequent War department census in my last post.)

Clara Rodriguez explains how the American invasion set many Puerto Ricans—like these families—moving:

The economy went from a diversified, subsistence economy with four basic crops produced for export (tobacco, cattle, coffee, and sugar), to a sugar-crop economy with 60 percent of the sugar industry controlled by U.S. absentee owners. The decline of the cane-based industry…in the twenties resulted in high unemployment, poverty, and desperate conditions in Puerto Rico. These factors propelled the first waves of Puerto Ricans to leave their country for U.S. cities—New York, for example—in search of a better life. (442)^^^

The United States government made 87 Hamilton the final destination for Lucile Kenn. In a way, it did the same thing for the Puerto Rican families whose lives Kenn acknowledged and whose (far too slim) stories she preserved for us.

^(For most of American history, having lodgers or extended family at home was the usual thing. When Henry Ford established his $5-day in 1914, he required his workers to live alone with their nuclear families. This was new. American households were seldom just parents and children. And even in 1940, perhaps especially because of the hard times brought on by the Depression, most households in the building took in lodgers to help pay the rent.)

^^In line with the shifting racial categories of the Census Bureau of the time, Kenn categorized everyone in the building as white. The history of those categories is big topic, one for another post. In the meantime, you learn about how Puerto Ricans “became white” from this article by Mara Loveman and Jeronimo O. Muniz, this related one by Loveman, or chapter 15 of Paul Schor’s Counting Americans.

^^^For more on this first wave, Rodriguez suggests Sanchez-Korrol’s From Colonia to Community: The History of Puerto Ricans in New York City, 1917-1948.