Waving the Dimpled Fist

Dear Reader, if you know a person born just shy of eighty years ago by the name of Judith Blane Gordon, please let her know the census found her back in 1940. Her father said she wouldn’t be counted, because she was a newborn. But she was.

Judith’s father, Ernest, made his false beliefs about the census and its attitudes toward his daughter very public. He also took the liberty of imagining (then voicing, then printing, then distributing widely) his newborn baby’s righteous fury at having been overlooked.

Judith arrived on the scene in early March on the eve of the 1940 census count, which was set to begin on the second of April 1940. Nearly every single day that March, the newspapers printed some new development in an on-going census controversy over whether or not Americans should be asked to disclose their incomes. (For more, check out the “Super Snoopers of Montevideo” and “Controversial Questions.”) Just two days before Judith’s birth, the front page of the New York Times printed Secretary of Commerce Harry Hopkins’s full-throated denunciation of Charles W. Tobey—the U.S. Senator leading the fight against the new census questions about income. Hopkins, the senior administration official overseeing the census, charged Tobey with “appealing for civil disobedience” and “urging an informational sit-down strike against the government.” Judith’s parents, Ernest and Sophia Gordon, reading the papers and listening to the radio (where Tobey had been appearing in prime time), decided to have some fun with the daily census outrage. That’s how the announcement of their first child’s birth took the form of a bit of old-school “fake news.”

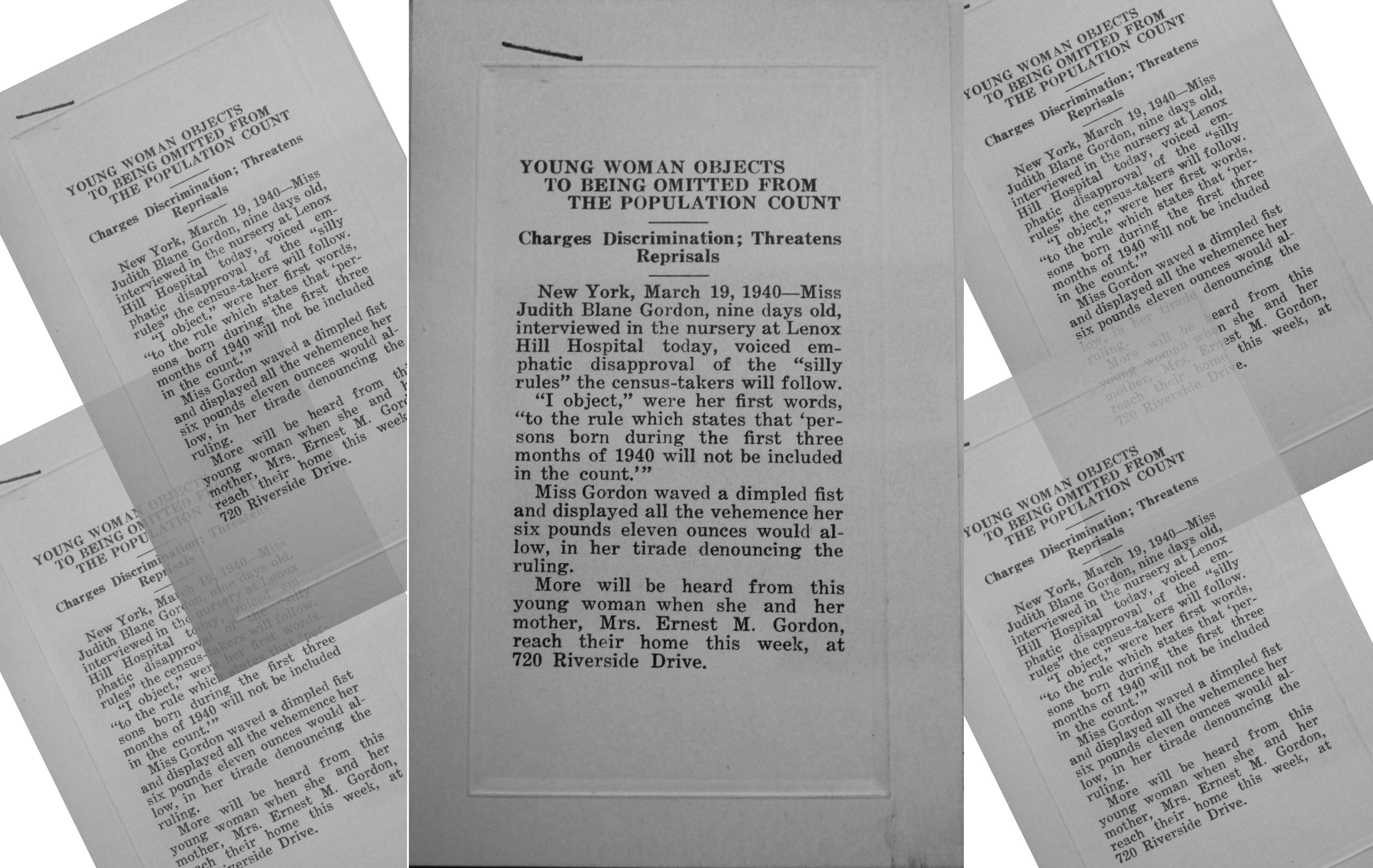

The headline declared: “Young Woman Objects to being Omitted from the Population Count.” The sub-head blared: “Charges Discrimination; Threatens Reprisals.” According to the article that followed, young Judith (“Miss Gordon” in faux-Times-style) “waved a dimpled fist and displayed all the vehemence her six pounds eleven ounces would allow, in her tirade denouncing the ruling.” What ruling raised such ire from so young and innocent a babe?^

The news-clip explained that Census officials had ruled against counting children born in 1940. None born in January, February, or (like Judith) in March, should be included as part of the American population.

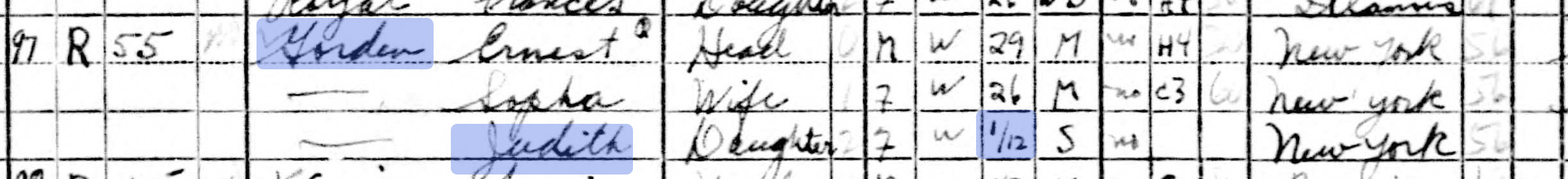

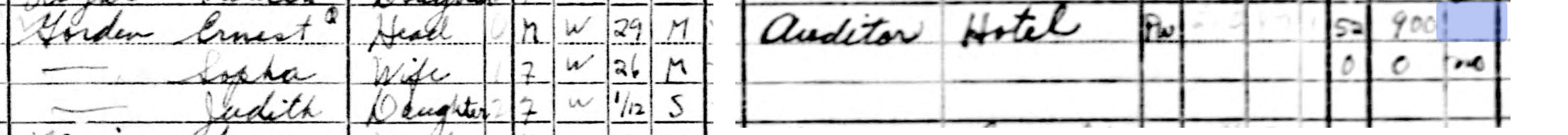

Yet, here, from 1940 is evidence of baby Judith’s enumeration.

She was in fact counted.

Gordon, Judith. Daughter, white, single, born in New York, and 1/12 of a year old.

Ernest, perhaps, had been confused.

If so, he joins a long line of fathers befuddled by the census. One of the most famous depictions of a census encounter, a painting from 1854 that hangs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, inaugurated the perplexed papa trope.

At the center of the image, painted by Francis William Edmonds, stands an amply fleshed Patriarch, his feet planted at his own hearth, where he struggles and strains with some great intellectual challenge—George Washington, the great Patriarch of the American nation looks on from a portrait over the fireplace. On the right stands a white-bearded, gold-vested census taker, accompanied by a boy bearing an inkwell. On the left we find his household huddled and smirking, three children peeking out from behind the skirts of a woman, probably their mother. The painting captures a scene that had played out across the country four years earlier during the census of 1850, the first census in the U.S. that did not just count the total number of people in each household, but kept a record of each individual’s name and personal information. When the census came calling, fathers everywhere tackled the task of providing this newly precise kind of household data.

The joke of the painting is: the master of the house struggles to name all of his own children!

The joke remains sadly pertinent even today. If the joke is funny at all, it now seems less “funny ha-ha” than “funny uh-oh.” Young children are one of the hardest to count groups of Americans. They tend to slip through the cracks, either not remembered or not reported. Maybe parents prefer not to mention a child or two whose presence might make their apartment seem too tightly packed. (The strict confidentiality requirements of the census prevent such data from ever getting into the hands of housing or health officials, and yet that won’t stop some people from withholding complete information, just in case.) Maybe a child who shuttles from one parent’s home to another, from the grandparents’ house to an Auntie’s flat, never gets listed as living in any of them. Maybe parents or guardians just think—like Judith’s dad Ernest—that little children don’t count. Whatever the causes, children fall through the cracks to an extraordinary and troubling degree. According to Census Bureau figures reported by Demographer William P. O’Hare, 1 in every 10 children aged four years and younger never got counted in 2010.^^ That adds up to more than 2.1 million missed babies, infants, and toddlers.

Ernest Gordon may have been a confused father, but Judith was a lucky child. She was counted and so in the eyes of the state, she counted. The same cannot be said for far too many of our fellow young Americans.

In truth, the Census Bureau in 1940 wanted very much to count babies.

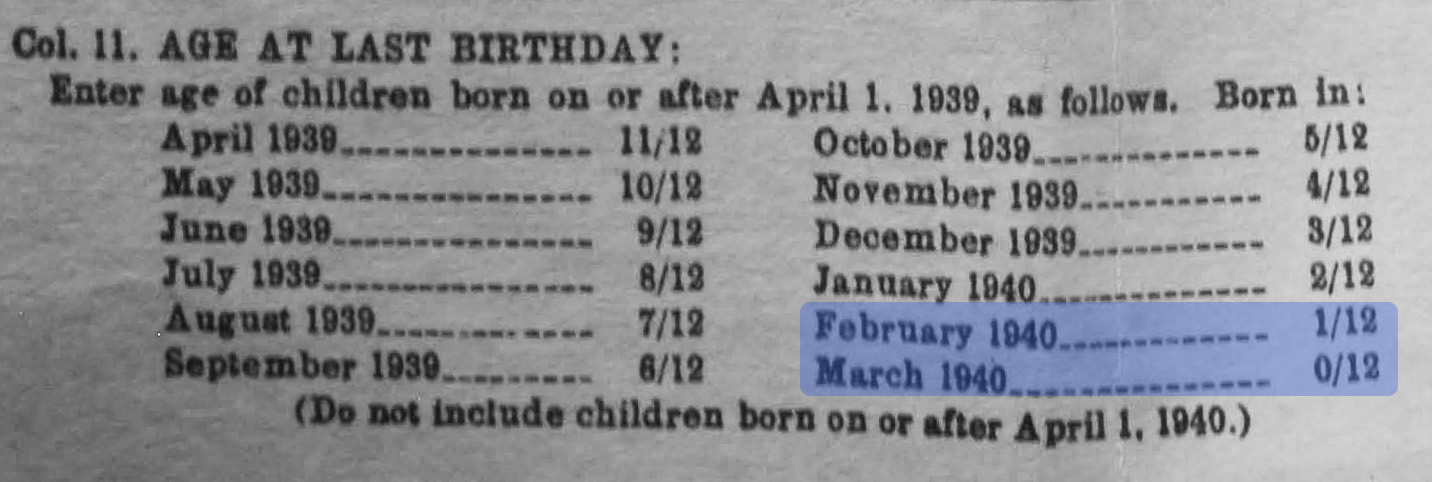

The Bureau invented a notation specifically to keep track of the ages of babies. At the bottom of each census sheet, enumerators saw a guide to help them report the precise age (in months) of infants. Here it is, reproduced from a sheet used in training enumerators:

April 1 was Census Day—the grand statistical fiction was that the census reported on the details of people’s lives exactly as they were on that day, even if the enumerator didn’t arrive to gather details until days, weeks, or sometimes even months later. So babies born after April 1 were not to be counted. Similarly, people who died after April 1 still were counted.

Therefore, the Census Bureau very much wanted to count Judith Blane Gordon, who was born on 10 March 1940. She was, by the Bureau’s reckoning, zero (0/12) months old on April 1. On that point, the confusion in this story grows. Ellen Morrison, the census taker who talked to Ernest at home on April 11, recorded Judith’s age as 1/12. Why? Maybe she did not understand the Bureau’s rules. Maybe Ernest said his daughter was a month old, and Ellen the Enumerator left it at that.

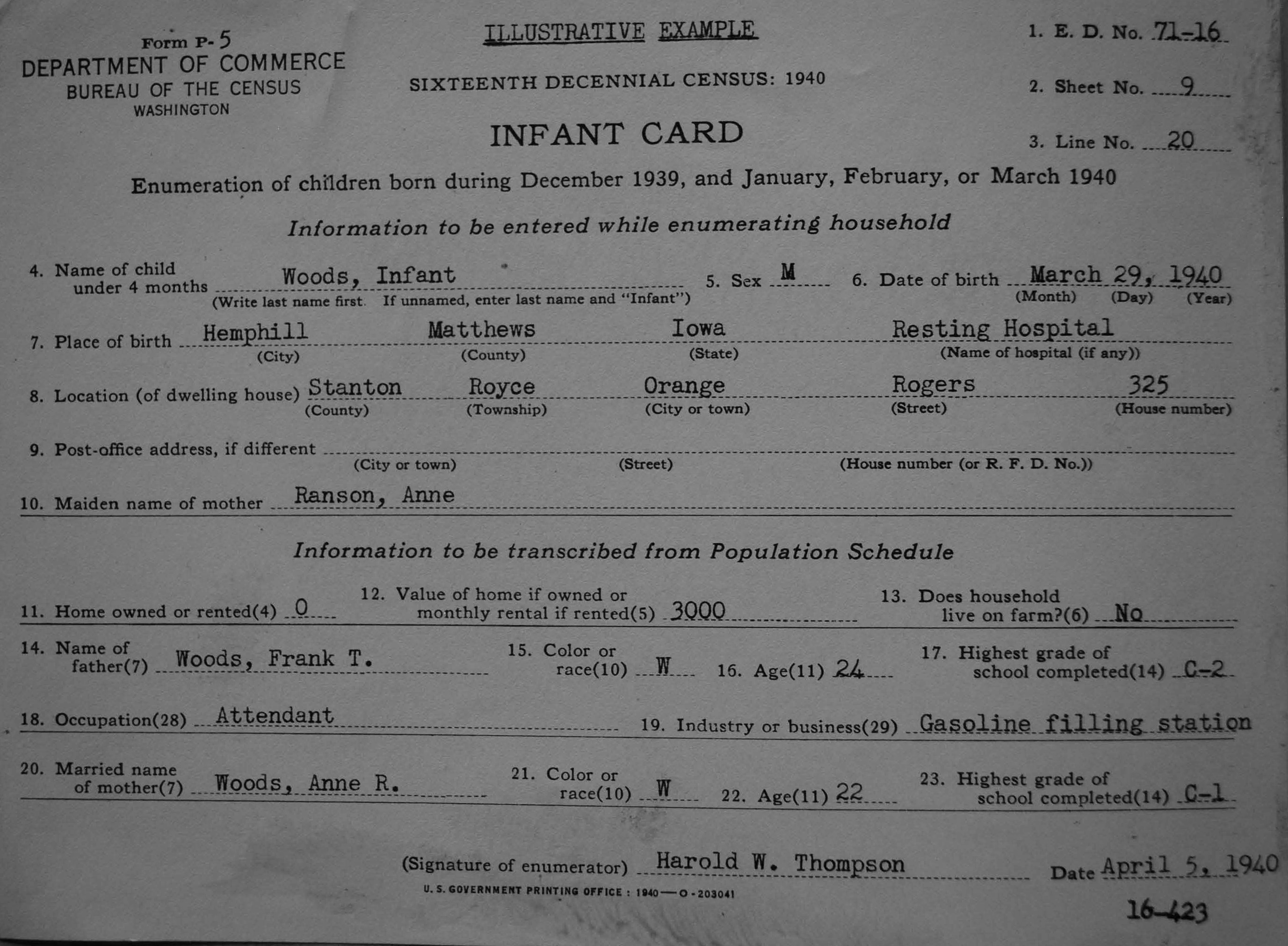

But Ellen Morrison should have known exactly when Baby Judith was born. The Bureau required its enumerators to fill out an “Infant Card” for any child four months old or younger—and that card had a blank requiring a precise birthday.^^^ I don’t have the card for Judith, but it would have looked like this, here filled out for training purposes:

So, it seems most likely that Ellen the Enumerator just did not understand the Bureau’s fractional infant age system. It’s hard to blame her, though. An age of 0/12 doesn’t even sound possible.

There’s one more possibility we should at least consider as we try to make sense of this odd birth announcement. It may be that confusion doesn’t account for Ernest Gordon’s error. He might have just decided it made for a better gag to pretend Judith wouldn’t count. And if his gag also sowed further dissension around the census, maybe that wasn’t such a bad thing either.

I stumbled upon this odd record of Judith Blane Gordon in a file of letters sent to Charles W. Tobey at the height of his attack on the census.

“Dear Senator:” wrote Ernest Gordon. “Here’s another point for our side!”

“You may quote my young daughter,” he continued, from the “attached birth announcement.”

Was Ernest on Tobey’s side? Did he object to a government enumerator violating his privacy?

It is possible. When Ellen Morrison came to ask him questions, he admitted and she recorded an income of $900 for his work as an auditor. But by way of Ellen’s carelessness or Ernest’s resistance, the question asking if he had any other source of income (of more than $50) was left blank.

Ellen certainly could be careless—we’ve already seen her get Judith’s age wrong and she also placed the Gordons on 150th St instead of on neighboring Riverside Dr—but this doesn’t look like Ellen’s error. She entered either “yes” or “no” answers to the question about “other income” for every other adult on the census sheet. Only Ernest’s answer was missing. In that absence, perhaps, we see further evidence that Ernest despised the government’s new inquiries into his income; perhaps in that omission he registered his objections.

I wonder, now, if Judith knows the political work she did as just a nine-month-old baby. I wonder if she’s seen the birth announcement, if she believes she was never enumerated. I wonder if she has the letter sent by Senator Tobey’s office in reply, one that did not bother to correct the birth announcement’s false statements about who could be counted, and instead challenged Judith and her “generation” to “vigilantly guard against any encroachment upon the rights of the individual.” Ernest Gordon asked specifically for just such a letter in return from Tobey—indeed, securing a signed letter might have been his principal reason for writing. At the close of his note to Tobey, Gordon asked again for a letter to Judith in reply, promising: “Such a letter will be prized by her many years hence.”

And so I wonder, does Judith—whose fists were once raised in dimpled anger—still prize that letter…If you, Dear Reader, should happen upon Judith, you might ask her (politely, unobtrusively). Be sure, too, to let her know that she was counted. And encourage your neighbors to ensure that their children will be counted this April!

^ Leave aside, for the moment, this deeper truth: babies expelled from a womb into the cruel, bright, arid world seldom need an excuse for outrage! And who are we to criticize them.

^^ The 2016 Census Bureau study that O’Hare reports discovered an “omissions rate” of 10.3%. The “net undercount” of 4.8% is half as high, indicating that about 5% of such children were counted twice in 2010. (7)

^^^ My guess is that the Census Bureau intended these infant cards to help test the extent to which each state and locality kept accurate birth certificates. In 1940, questions still dogged the birth certificate infrastructure. This was the first census after the last state in U.S. had been judged compliant with common birth registration standards, just seven years earlier. I assume the nation-wide count seemed a useful opportunity to confirm that the system still worked. For more on how and why birth certificates became ubiquitous see Susan J. Pearson, “‘Age Ought to Be a Fact’: The Campaign against Child Labor and the Rise of the Birth Certificate,” Journal of American History 101, no. 4 (2015): 1144-1165.