A Well-Known Fact

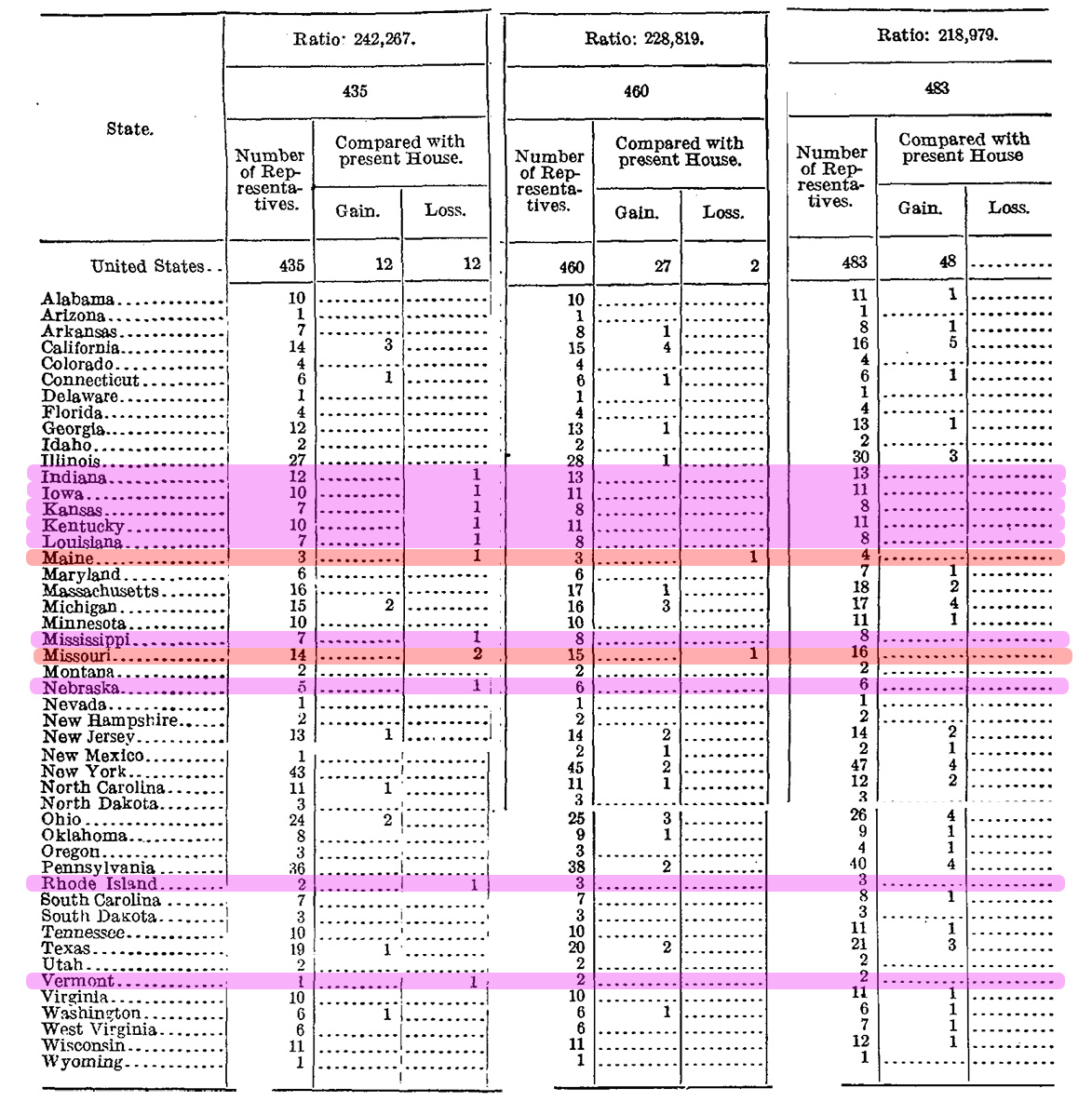

Today we take for granted that the U.S. House of Representatives has 435 seats. Which state gets which seats changes as some state grow faster than others, but the total number stays the same. But that was not the case a hundred years ago. That is why, in December 1920, the Census Committee of the House of Representatives called Joseph Hill, the Census Bureau statistician, to testify. He brought with him a set of 49 tables of numbers, based on the final 1920 population counts for each state, showing the appropriate distribution of seats among the states in a variety of possible Houses.

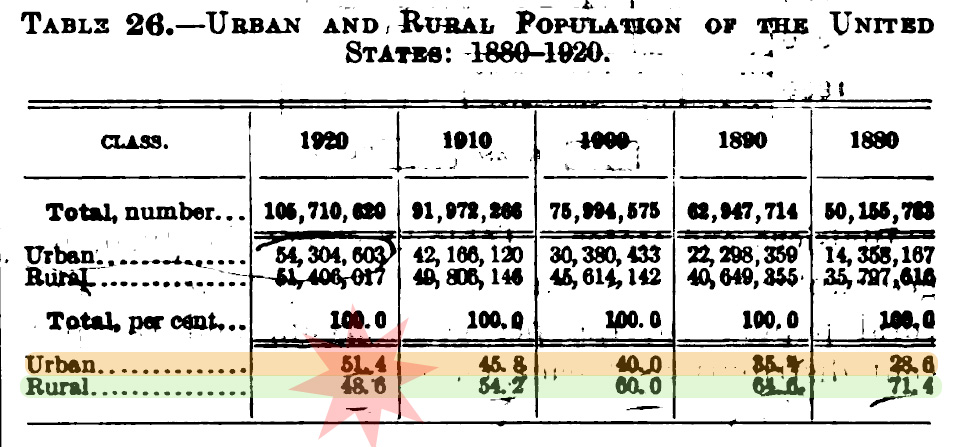

The committee wished to see how the seats would shake out for a wide range of Houses. I’ve excerpted the table for three Houses, of size 435, 460, and 483 above. The values and concerns of Congress structure the tables. After naming the states and listing the total representatives due to each, the tables show which states gain and which states lose in the apportionment. The reason that the table stopped at 483 was plain to all: that was the value at which no state would lose a representative. (I’ve highlighted in purple any state set to lose at least one representative in the 435 scenario and in red any state that would also lose a representative in the 460 scenario.)

The Republican party fought within its ranks over the right way to handle the apportionment in 1921. The party’s leaders sided with those calling for greater “efficiency” in government. They decided the House should remain at its present size, 435 members. (This decision was convenient too for representatives in states that would neither gain nor lose a seat at 435, since it meant that their state would not redraw the district lines in some way that might imperil their re-election.)

Against his leadership’s wishes, the Republican chair of the Census Committee, Isaac Siegel of NYC, championed a bigger House. He and his colleagues pointed to the growing nation, the new responsibilities of taking care of the World War’s veterans, and the swelling ranks of women voters after the passage of the 19th amendment. There was another motivation for enlarging the house and the power of the motivation could be read in the particular size Siegel chose for his bill: 483. That was the smallest possible House where no states lost a representative. Siegel didn’t want any of his colleagues, or their states, to lose a seat.

Losing a seat in the House embarrassed the state that lost it. Losing a seat in the House guaranteed that a member of the current voting Congress wouldn’t be coming back. For small states, losing a seat might mean not just losing a member, but losing a member who chaired a powerful committee, a member who pulled strings and knew the strings to pull. Losing a seat was a big deal, a terrible fate. The Congress—and the nation—was about to discover the extreme lengths to which states would go to avoid that fate.

In the previous chapter of this story, we saw how the polymath James Weldon Johnson and the NAACP presented data and made their case that Southern states had disfranchised Blacks and so, as required by the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, should have their representation in the House drastically reduced. The case was a powerful one, but one that Congress proved adept at ignoring.

It did not help that the Census Bureau left obscure the theft of the ballot from African Americans in the South. The census schedule asked no question about voting and the Bureau’s staff defined demography so as to exclude voting. When the Bureau published a significant report in 1915 on Negroes in the United States, it discussed birthplaces and occupations, morality and illiteracy, but it never once mentioned the fact that most of the population under examination had recently been robbed of a fundamental political right.

The statistical invisibility of disfranchisement excused the Congress for ignoring it. Massachusetts’s George Tinkham proposed an amendment that would add to the apportionment bill a clause affirming the responsibility of Congress to decrease the representation of states that disfranchised their citzens. Then a bipartisan alliance kept him quiet and justified their actions by pointing to the absence of data. The Democratic leader Finis Garrett of Tennessee accused Tinkham of “creating this utter confusion and chaos.” His most damning critique of Tinkham’s amendment was that it “presents no specific number of Representatives to be apportioned to any State.” He continued: “It offers nothing certain for the certainty which it would destroy.” Across the aisle, Frank Mondell of Wyoming, the Republican majority leader agreed and explained the root of Tinkham’s failure: “my understanding is that there is no information available on which we could now act intelligently, and that is no doubt the reason why the gentleman from Massachusetts has presented no plan or provision for the carrying out of the provisions of the fourteenth amendment.” To succeed, an amendment punishing states that suppressed the vote needed hard numbers, but Congress and the Census Bureau had seen to it that such hard numbers did not exist.

(In this and all subsequent debates, the House also improvised a one-man gag rule. Someone always objected to a request “by unanimous consent” granting permission for all members to revise and extend their remarks for publication in the Congressional Record. Yet when each individual member asked for that permission, none objected. Until Tinkham asked—then, someone objected, every time. Tinkham alone was barred from revising and extending his remarks.)

As Michelle Murphy explained in her magnificent 2006 book, scientific investigations make some things newly visible, but they also make it impossible to see other things, things defined out of existence, things placed outside the focus of the microscrope. A “regime of invisibility” allowed Congress to say: we have no numbers, no evidence to use in decreasing the representation of Southern states, even if they were inclined to do so. Congress was not inclined to punish the South, though, which was one reason that the regime of invisibility persisted, one reason that James Weldon Johnson and his colleagues had worked extra hard to puncture the wall of knowing ignorance. But it was all to no avail against such intentionally engineered ignorance.

In contrast, the census invited readers to see a massive transition, the transition that came to stand at the center of debates over how to apportion the U.S. Congress.

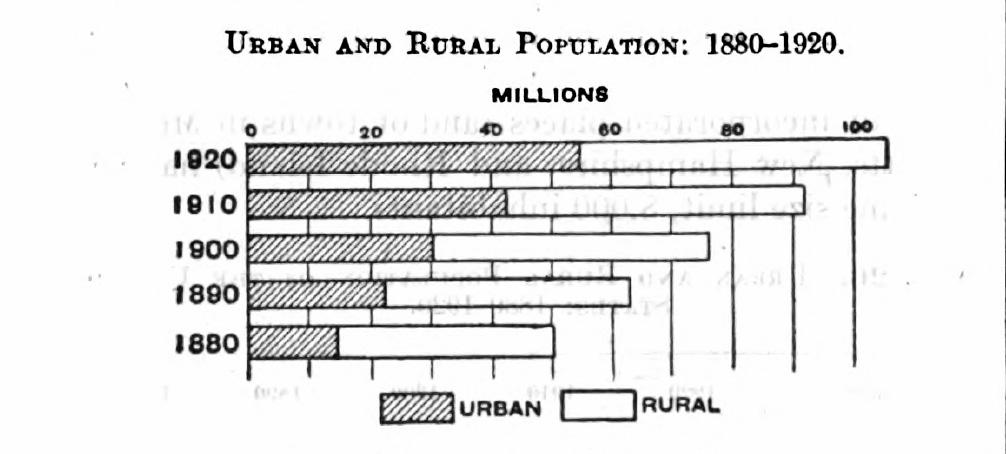

The 1920 census showed that the United States had become an urban nation. Census officials published a chart making visible this milestone of demographic transition.

The shaded “urban” area in the chart filled only about a third of the nation’s bar chart in 1880. Forty years later, it had sprawled and grown such that it covered more than half of the total population graph. 51.4% of that graph, to be precise.

In October, 1920, Sam Rogers, the Census Director, identified an accelerating “trend” driving toward greater urban concentration. “For the first time in the country’s history,” he announced, “more than half the entire population is now living in urban territory as defined by the Census Bureau.”

But was it?

Was it really?

Rogers’ closing clause is crucial here: “as defined by the Census Bureau.” The census defined any town of 2,500 people or more as “urban.” There was no “suburban” in those days, and so perhaps this made some sense. But the tiny town where I teach—Hamilton, New York—has around 2,500 usual residents and one would be hard pressed to find anyone who would call it “urban.” Bucolic, maybe. Quiet, certainly. Rural even, probably. Not urban.

Setting the urban/rural threshold at 2,500 people created some patent absurdities. Even Census Bureau officials thought so. Joseph Hill, the census statistician and not incidentally a New Hampshire native, complained that the census had in 1910 declared that two Massachusetts counties were entirely urban. Most outrageous, he thought, was the treatment of Nantucket, which had 2,962 residents and so counted as urban.

Hill knew for sure that Nantucket (the Nantucket pictured below in a 1910 photo)

was not urban.

Nor was there anything natural about the 2,500 person threshold. Hill traced the threshold as an official limit only to the 1900 census. And from the looks of things, the Bureau only had historical data for that threshold back to 1880. That’s why the chart stopped where it did. That was all the Bureau could see. Earlier, urban places had to be bigger.

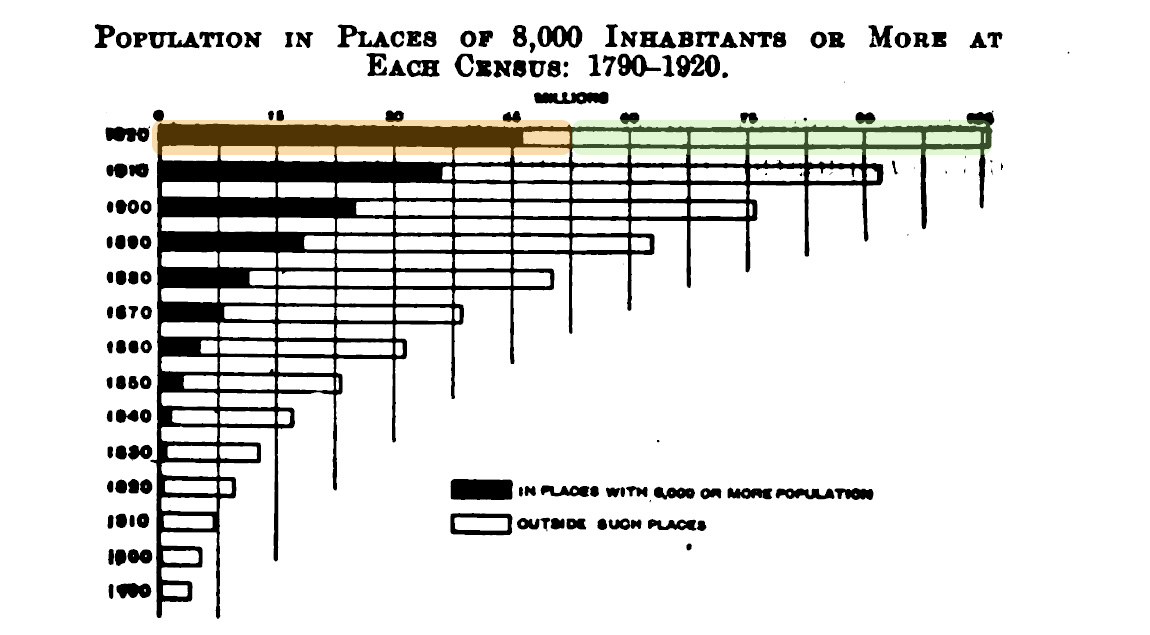

To see into the deeper past of an American march toward urban dominance, one had to adopt the older urban/rural threshold set at 8,000 people. That produced this chart.

That threshold made America rural again.

(The orange-brownish highlight and the green highlight meet at the halfway-mark for the 8,000 person threshold. The darkened urban population falls a good bit short.)

The game had been rigged sometime in the late nineteenth century to speed up the march of the United States toward the moment when the cities would appear to rule. I suspect, oddly enough, that it was rigged by those who feared the cities—or who feared the inhabitants of the cities. (For more on those suspicions, see the footnote at the end of this post.)

Some newspapers picked up the story of this transition. One reporter accepted the premise, and interpreted it through a racialized lens. “The America of our grandfathers was a land of blond men of Nordic or so-called Anglo-Saxon blood, who lived outdoors, tilled the soil, herded cattle, hunted, fished and sailed the seas from Arctic to Antarctic,” wrote Frederic J. Haskin in the paper. “The America of our grandsons will be a heavily populated country of short dark-skinned men, living for the most part in the most crowded, complicated and enormous cities the world has ever seen depending on manufacture, trade, and commerce for their living.” Haskin deemed this “transition” to be more or less “inevitable.” He seems, at best, to have been ambivalent about that inevitability.

Members of Congress also heard the story that the United States had become more urban, more industrial, and it shaped profoundly how they interpreted the fight over enlarging the house. James Aswell, whose state of Louisiana was slated to lose a representative at 435, said that voting against a larger house was tantamount to voting for the perversion of American democracy. I can almost hear him thumping his desk as he said these words:

An argument against this bill is an argument to reduce the representation of 11 agricultural States;

it is an argument for the pernicious lobbyist here, against the will of the people;

it is an argument for special privilege against the average citizen;

it is an argument for the rich and the mighty against the poor and the weak;

it is an argument for the reactionary against the progressive;

it is an argument for autocracy and centralization against democracy and popular government.

This prose poem, an ode to democracy championing the poor and weak, stood out to me too because its author had also been one of chief voices quelling any discussion of disfranchisement. Aswell stood up for the poor and the weak, perhaps, but not if they were Black.

Frank Greene of VT (set to lose a seat in a smaller House) acknowledged an “inevitable drift of mankind toward city building,” but lamented “the gradual diminishing of the steadying influence of the countryside” on government.

Thetus Sims of Tennessee didn’t hide his disdain for the rising cities. “More than half of the population of the United States are in our cities and towns that exceed 2,500 in population,” he said. “In a little while the cities which are boss ridden, boss ruled, and ring controlled will have a large majority of the membership of this House.” A vote for a smaller house, for taking seats away from “agricultural” states, was a vote for the bosses, he said.

Edward Little of Kansas (set to lose a seat in a smaller House) warned against America—“a Nation that began at Concord and Lexington” (which for these purposes, I guess, were definitely rural)—allowing “that her councils be dominated by semicivilized foreign colonies in Boston, New York, Chicago.” Here Little brought to the surface the racism and nativism roiling beneath all the talk of city bosses and the steadying countryside.

Hubert Stephens of Mississippi commiserated with his sectional peers. “It is unfortunately true that the last census shows that there are more people in the cities than in the rural districts. That is not a healthy state of affairs for the Nation,” he judged. But he also added “No matter how much we deplore it, it is the fact.”

Not everyone agreed with him, about the “fact” part. “It is suggested that there will soon be a drift from the cities back to the country,” said Stephens, and though he sloughed off such talk—“we cannot legislate on speculation”—he knew to take seriously those who made such suggestions. Some of them who refused to accept that the cities were taking over were his fellow Mississippians (whose state would lose a representative at 435).

Johnson of Mississippi, for instance, came armed with a quiver of alternative facts. “It is a well-known fact” was how he began a litany of objections to the 1920 count. “It is a well known fact” that the Census Bureau struggled to hire and hold on to good enumerators in a tight labor market. “It is a well known fact” that many Mississippians went uncounted as a result. And beyond those in Mississippi who weren’t counted, there were those not in Mississippi who still belonged to the state, who should still be credited to the state’s accounts.

Johnson revived the talk of “abnormal” conditions that had so worried Congress before the census. Now he amplified the abnormalities to cast doubt on the census’s facts. Johnson summoned the memory of “special trains carrying thousands of Negroes and a great many white people to the northern cities” in the war years. But the migration had been temporary, he insisted. “Hundreds and thousands of these same people are trying to return to the South,” he said, but they would go unrepresented in a smaller House that took away seats from Mississippi and its Mississippi-valley neighbors.

Thousands! Thousands! Thousands! thundered Johnson. Thousands of Mississippians had been displaced and miscounted:

Thousands of her citizens are temporarily employed in other sections of the country, and they were enumerated.

Thousands of her citizens, mostly colored, were temporarily removed to Chicago and other places before the recent election, to be used politically.

They have been used and are now returning to their homes, poorer but wiser.

These people should have been enumerated as citizens of Mississippi.”

Terrible are the tears of those mourning lost representation for those whose ballots the mourners have already robbed.

For members of Congress in states set to lose a representative, the movements of people during war were like the movements of water under the heavens. Horace Towner of Iowa (set to lose a seat at 435) believed a “recurrent wave will bring back their own to the rural district.” Oscar Bland of Indiana (set to lose a seat at 435) mixed his metaphors. He began electro-magnetically— “During the war the great activities in the big cities of this country drew men form the farming communities of the Nation like a magnet”—but soon succumbed to the gravitational pull of celestial influence: “The time must come when this tide must flow back.”

At times, the critics also railed against the tyranny of counting and facts and tables. As Greene of Vermont put it, “a popular government is not made a success merely by being based upon tables of mathematics.” But Greene and his colleagues weren’t categorically against reapportioning, or against the census even. They could live with the results of this census they deemed abnormal, so long as their states (and they themselves) didn’t lose a seat because of it. They could live with an abnormal census, if the House contained 483 seats…

FOOTNOTE: The move from the 8,000-person threshold to the 2,500-person threshold came around the same time that Jacob Riis published How the Other Half Lives (1890), a book that exposed to readers across the nation and the world the conditions in which New York’s working poor lived. They lived, one stacked upon the other, in crowded tenement buildings like these from the book’s frontispiece:

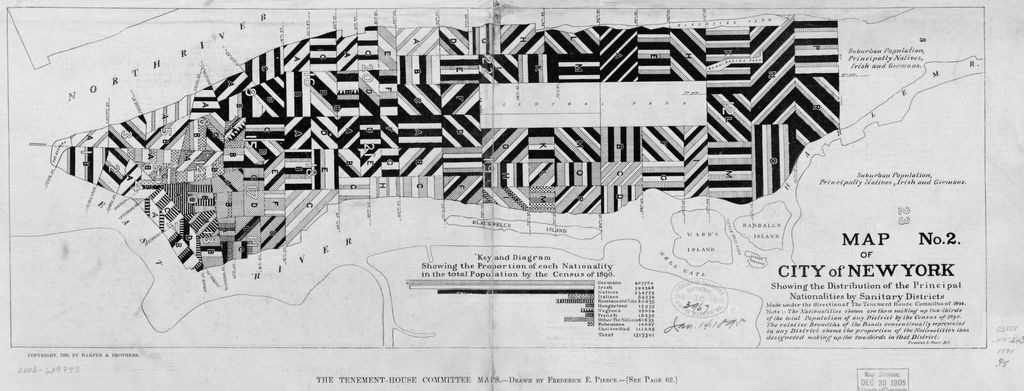

Riis spoke of the “mixed crowd” living in the tenements, of alleys teeming with people, but “not a native-born individual” among them. “One may find for the asking,” wrote Riis, “an Italian, a German, a French, African, Spanish, Bohemian, Russian, Scandinavian, Jewish, and Chinese colony.” (21) Five years later, New York’s Tenement House Commission mapped Riis’ colonies, covering Manhattan with the craziest of quilts.

Cities—urban spaces—meant more than congestion, they augured an invasion of foreigners. “Our early history,” wrote the historian Frederick Jackson Turner, “is the study of European germs developing in an American environment.” (Erasing African Americans and Native Americans as he went.) But that all changed in 1890 when the Census Bureau announced that it was no longer possible draw a “frontier” line on its maps of the country. The disappearance of the frontier was also part of a rigged game, and aided by some misleading data visualizations. The had been the invention of Francis Amasa Walker, a committed nativist and campaigner for immigration restriction, with a message. In an 1896 Atlantic Monthly essay, Walker argued that the closing of the frontier (which he had made visible, made real) necessitated the closing of the United States’ borders. With no more free public lands (expropriated from Native Americans), he argued that it was impossible for the U.S. to continue “offering indiscriminate hospitality to a few millions more of European peasants, whose places at home will, within another generation, be filled by others as miserable as themselves, would not compensate for any permanent injury done to our republic.” If there was no longer a frontier to absorb and Americanize the immigrants, what choice was there beside halting immigration? (About 13-14% of the U.S. population was foreign-born throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. Today it’s again around that historical norm.)

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Census Bureau officials made the frontier disappear around the same moment that the they rejiggered the urban/rural threshold to bring on a quicker moment of transition. Sam Rogers may not have known it, but one of his predecessors had set him up to be the one to declare a nation now more urban than not.

This post is published under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license by me.