The Harvard Mimeograph

I began writing this essay before setting out on a camping trip. Sitting in the passenger seat of my partner’s truck, our child and two small dogs crammed between us, I thought of a summer vacation I’d just been been tracking through the archives. In 1940, a Census Bureau official drove out to the Berkshires in Massachusetts to find the summer home of a Harvard professor. They had matters of strategy to discuss, as they sought victory in an abstruse methodological controversy that had already endured two decades, and had already helped justify a gross failure of American democracy.

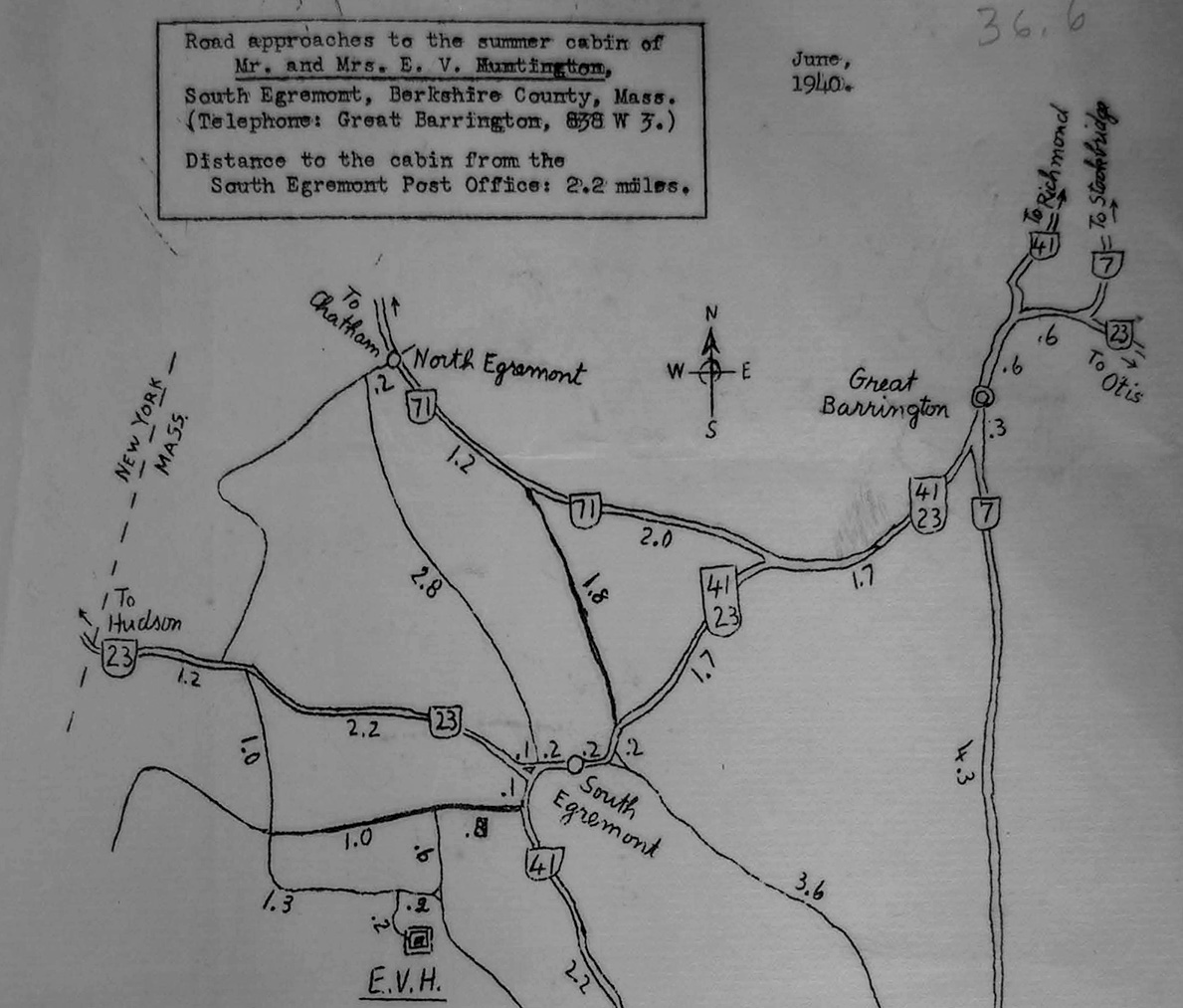

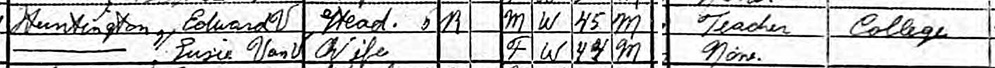

Morris Ullman, a young Census Bureau statistician, trekked out to find Edward V. Huntington. To guide him, he used a mimeographed map mailed by Huntington. It is a tellingly numerical document, each leg of each route precisely measured, with a legend at the bottom showing the distances of Huntington’s cabin to nearby cities in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New York. It even provided the distance from Huntington’s usual home in Cambridge, MA: 144 miles. It was a form letter as well as a map, with a generic “June” dateline and a space for a date to be penned in if necessary. Huntington couldn’t even go on vacation without quantifying it, or without running his mimeograph.

No records remain of the conversation that Ullman and Huntington had, but we can be sure it centered on their shared intellectual and political project: to convince the United States Congress to adopt a particular method—called “equal proportions”—for deciding how many representatives each state deserved on the basis of its census population.

As we arrived in the Adirondacks and reached the summit of our first hike-able mountain, I day-dreamed about Ullman’s trip, thinking how strange it was that this government official had teamed up with an Ivy League mathematician to convince Congress to pick one algorithm over another, a choice that often had no effect on how representatives were apportioned and seldom affected more than a handful of representatives in a handful of states. But to them it was a crucial question, and one with only one correct answer: theirs. Congress had to see it their way. This methodological debate clearly mattered to its participants.

(The view from Coney Mountain, where the daydreams happened:)

How should it matter to history?

It is surely part of a larger story, one told by Margo Anderson of “antiurban and antidemocractic laws” propped up by census data, by “‘scientific’ rules and mechanisms to justify their conservative intent.” As Anderson tells it, conservatives in the 1920s used census data to make more acceptable both a severe restriction of immigration and a decade-spanning theft of power from growing centers of (increasingly urban) population.

It is also, more generally, part of a larger story of “Democracy by Numbers,” to borrow Alma Steingart’s wonderful phrase. Steingart examines the methods controversy for all it can possibility tell us about “the possibility of objectively measuring fairness.” Each side believed that a fair, unbiased, objective measurement was possible, argues Steingart. And attending to their fights over those methods can help us better understand similar efforts to bind fairness to science, whether in terms of new efforts to combat gerrymandering with computers or, I’d add, in every new promise of an unbiased algorithmic solution.

What we cannot afford to do is to separate the “technical” debates of the scientists from the “practical” maneuvers of politicians, as Charles W. Eagles does in his otherwise exemplary, in-depth study of the failure of apportionment in the 1920s. As we will see, those who do technical work must understand themselves as political actors, whether they like it or not. Huntington didn’t like it, and denied any political action aside from standing up for “the truth.” But the consequences of his mimeographs tell a different story.

Finally, there may be lessons in this story too for those of us anxiously awaiting another apportionment in 2021 premised on the results of the 2020 census? As the researchers Michel L. Balinski and H. Peyton Young argued in 2001, the methods controversy settled in 1941 with Huntington’s victory, but it did not have to settle the way it did. Huntington’s method wasn’t, and isn’t, the only fair or viable method. In the coming months and years, perhaps unsettled times will unsettle the matter of apportioning power among these United States.

The methodological controversy arrived in 1921 as a letter to a New York Congressional representative. It is not clear that Congress would have cared about the letter much at all, had it not appeared momentarily useful, as a desperate weapon wielded by the weaker side.

New York’s Isaac Siegel received a letter in one Wednesday morning in January 1921 and he brought it with him to the floor of the House of Representatives. The letter had been sent by the head of Harvard’s engineering school, Edward V. Huntington, and it contained information that cast “doubt”—actually, “grave doubt” in Siegel’s words—on the justice of the apportionment in the bill then under consideration. The second day of debate had just begun considering the apportionment bill that Siegel’s committee had voted to recommend—and that bill, Siegel’s bill was in trouble. His bill allowed the House to add 48 members, up to a total of 483 that were to be “apportioned” among the states according to each state’s population. Siegel’s bill prevented any state from losing a seat in the reapportioned House. But Siegel’s party leadership had thrown its weight behind a California representative’s amendment to keep the House at only 435 seats, dooming 11 states to lose at least one member. Siegel could read the writing on the wall—if a vote was held that day as was planned, he would lose.

Huntington’s letter could save the day. There’s no way to know what Siegel really thought about Huntington’s methodological qualms. But he hoped he could use those qualms to get the House to do what he wanted.

Three days earlier, the Sunday New York Times ran a letter to the editor written by Huntington. That letter made Huntington a public figure and signaled the beginning of a decades-spanning scientific and political controversy. In that letter, Huntington (signing his letter as a Professor of Mechanics) called attention to an “injustice” that he had discovered in the proposed reapportionment bill for 483 members. That letter was published exactly one year and one day after Huntington himself had been enumerated in the 1920 census.

Huntington explained that the Census Bureau’s calculations, using a method called “major fractions” refined by Walter Willcox a few decades earlier, gave Missouri 16 seats and Montana 2. Missouri got 8 times the representation, despite having only 6.28622 times larger a population. Huntington had devised a different method of apportionment, which he came to call “equal proportions” that handed one of Missouri’s seats to Montana instead. Huntington’s method gave Missouri 5 times the representation of Missouri, which was still far from perfect—but Huntington argued it was better to under-represent Missouri by 25.7% (using his method) than to over-represent it by 27.3% as the major fractions calculations did.

For a House of 483 members, Huntington’s method only shifted one seat, affecting two states. Huntington worried that readers might judge it merely a statistical molehill. He needed them to see it for the mountain it was. “It should be remembered,” he wrote, “that what is really involved is a mathematical principle which admits of no gradation between truth and falsity.” Huntington called the Census Bureau’s major fractions calculations unjust and in error. He admitted no room for uncertainty.

That language of error and injustice played into the hands of those, like Siegel, who sought a bigger House. They were already casting doubt on the validity of the census count, claiming it captured a picture of America as an abnormal moment when war had displaced millions of rural residents. Now Huntington provided a reason to cast “grave doubt” on the apportionment calculations made using census data and he asked for permission to speak to Congress before it acted erroneously. “What harm could come of delaying this matter for a few days until it could be thoroughly investigated?” asked Mississippi’s Paul B. Johnson—one of House’s chief purveyors of doubt on Tuesday, January 18, on the first day of debate. As a matter of fact, now that Henry Ellsworth Barbour’s amendment for a smaller house was not just being considered, but looked likely to win, Johnson and Siegel and their allies loved the idea of a delay—if there was any reason to postpone a vote that they would likely lose, they were for it.

Huntington soon provided more reasons for that delay. When he heard about an imminent amendment to keep the house at 435, he sent a new letter to Siegel. (Huntington probably read that the Republican leadership had decided to back the 435-seat amendment in the 17 January 1921 New York Times. He had the calculations for a 435-seat house completed already because the savvy Hill had told him to prepare them.) For a 435-seat House, Huntington’s method now differed from the method of major fractions in six states: New York, North Carolina, and Virginia would each not get a seat promised by the major fractions calculations, while Rhode Island, New Mexico, and Vermont would each get an additional seat. Siegel’s own New York would be hurt by Huntington’s method, as he explained to his colleagues, and yet still he said it was his duty to raise the issue and that it was duly explored. Huntington promised to be in Washington, D.C. for a conference in two days, on Friday, and could appear before Congress then to explain the issue. Siegel suggested that Congress accept his offer.

Confusion and chaos ensued briefly. Some representatives took Siegel’s comments and Huntington’s letter as further evidence that fundamental errors plagued the 1920 Census. Since sowing doubt about the census had taken a prominent place in his side’s political strategy that day, Siegel resisted the urge to clarify his points, until his opponents forced him to. Barbour, whose 435-seat amendment looked poised to win, grew exasperated and threw his support fully behind the authority of the Census Bureau:

Dr. Hill, the statistical expert of the Census Bureau, our own Government Institution for the gathering of statistics, appeared before our committee and assured the committee that these figures are correct. This letter which is presented here this morning is merely the statement of some statistician who differs with Dr. Hill’s method….Are we going to follow the recommendations of our Census Bureau or are we going to take the word of some theoretical man who disagrees with our own officials?

Barbour won that argument and carried the day. His amendment for a 435-seat house garnered 269 votes while Siegel’s side only mustered 76. The amended apportionment bill passed by a voice vote. And that should have been it. The House should have been apportioned then, as it had been every ten years. But it wasn’t.

Huntington refused to let it go. He wrote to the chair of Senate Committee on Census, Howard Sutherland of West Virginia, begging that the Senate delay considering the bill until his method could be considered. Sutherland obliged and asked the Census Bureau to convene its external advisory committee to adjudicate the methodological debate. Sutherland asked for a judgment as to which method was “scientifically more accurate and fair.” Hill, who had enough experience with Congress to smell something funny, wrote the advisory committee’s chair that he did not think Sutherland would bring the bill to the floor for a vote. Since 11 states stood to lose members in the smaller house, and each state had two senate votes, 22 Senators or nearly a quarter of the Senate, had a direct interest in opposing the bill passed by the House. Rather than let their methodological dispute serve as a smokescreen for their self-serving behavior, Hill counseled the advisory committee to stand up for tradition. He wrote:

the only thing to do is adhere to precedent, enacting the bill in the form which it has passed the House and reserving for future consideration the question of whether the method of apportionment is the best one or the correct one.

But that did not happen either.

The Senate let the House bill wither, as Hill had predicted. The Census Advisory Committee decided in favor of Huntington’s method. But when Siegel put forward another apportionment bill to a newly convened Congress in October 1921, this time for a 460-seat House, he avoided the issue since the methods agreed on the apportionment for a house of that size. In the end, it didn’t matter: the forces insistent on keeping the House at 435 members won again, narrowly voting to send the bill back to the Census Committee, never to be heard from again.

The U.S. Constitution required a census every ten years so that Congress could apportion itself to reflect the movements of the nation’s population. With the October failure of the apportionment bill, Congress failed to meet its constitutional obligation, and would continue in that failure for another decade.

The methodological controversy refused to die. The scientists in and around the Census Bureau kept it alive. A “battle of methods” ensued.

In fact, in the national archive I found this sentence scrawled across the lid of a decaying folder:

Contemporaries also sometimes called it the “war of the quotients.”

The battle was founded on the belief that there could be only one true solution, a belief that preceded Huntington’s letter by half a decade. His adversary, Walter Willcox, first made the claim that only one truly fair apportionment scheme could exist in a December 1915 presidential lecture before the American Economic Association—and Willcox claimed to have discovered that one true scheme. He had premised it on a close study of Congressional behavior and believed it mechanized the priorities that Congress had held to since about 1840—Congress in turn had used it to apportion itself in 1910. He further argued that major fractions met criteria that mattered to academic theorists, and even claimed that the Cornell Math Club preferred his method. He summed up his case: “Thus the theoretical arguments of statists and mathematicians point to the same conclusion to which Congress had already been brought by other considerations and establish my thesis, that the method of major fractions is the correct and constitutional method of apportionment.”

Willcox had gone before fellow economists seeking allies against a battle that he hoped would never break out. Joseph Hill—who had once been Willcox’s employee at the Census Bureau—had devised his own method for making the apportionment. Willcox hoped to kill that alternative before it could take root.

Both Hill and Willcox had seen how Congress worked and thought it could be rationalized by some mathematical rules. Willcox devised a method premised on the arithmetic mean—if a state deserved half of a Congressperson it was guaranteed that seat. The arithmetic mean between 1 and 2 seats is 1.5 seats and between 42 and 43 is 42.5. If Vermont deserved 1.43 seats, it only got 1; if New York deserved 42.51 seats, it got 43. Hill’s method in turn was premised on the geometric mean—here the math gets a bit more complicated. (Willcox always liked to say his way was better because no one in Congress could understand Hill’s.) The geometric mean is a strange kind of average, one that represents the number that, if multiplied by itself (squared) would give the same result as the multiplication of the numbers being averaged. Which is to say that you get a geometric mean by taking the square root of whatever you get by multiplying together the original numbers. So the geometric mean between 1 and 2 is sqrt(1x2)=sqrt(2)=1.414. That’s a lower bar to pass than 1.5 for Vermont. New York by contrast, would have to get past sqrt(42x43)=sqrt(1806)=42.497. That’s still less than 42.5, but just barely. Using the geometric mean made it easier for states with smaller numbers of representatives to earn an extra representative. And since there were only so many seats to give away, making it a tiny bit easier for small states made it a tiny bit harder for big states.

Willcox knew about Hill’s method, and so did Congress in 1910, but both pushed it to the side.

Hill, with the 1921 apportionment approaching, dusted off his idea and sent it to Harvard, where it was passed around until it landed on Huntington’s desk. Huntington revised the technical implementation of the method and gussied it up with a formal mathematical apparatus.

Huntington also erased Hill as an author, claiming to be the method’s inventor in his letters to Congress. Hill fell in line, explaining to a colleague: “Huntington’s method rests on the same principle and is, as I look at it, my method perfected and mathematically demonstrated.” In the next line he admitted the demonstration was “not easy to follow for those who have no expert knowledge of mathematics,” and I cannot help but think that Hill himself didn’t really understand what Huntington was saying. (On matters of serious mathematics, Hill routinely turned to Elbertie Foudray.)

So Congress in 1921 was called on to adjudicate between two claims to absolute truth: between major fractions and equal proportions, the arithmetic mean and the geometric mean, small states and big states. It punted to the Census Advisory Committee, a recently constituted body staffed by members of the American Economic Association and the American Statistical Association. Willcox was a member, but had to recuse himself, and he soon discovered that his efforts to lay the groundwork in 1915 had failed. The committee’s report advocated for Huntington (and Hill)’s equal proportions method and added yet another wrinkle. The committee claimed that Willcox’s method minimized the the disparities in representation for individuals—it led to the smallest absolute differences in terms of how much representation each person received. That sounds like a ringing endorsement today, steeped as we are in the doctrine of one person, one vote. But one person, one vote grew out of the work of Civil Rights advocates in the 1950s and 60s. The committee in 1921 read the Constitution to be most concerned with equalizing representation among states rather than individuals, and for that the method of equal proportions performed best. Equal proportions, they said, minimized the relative difference in the ratios of representation to population for states—and that, they said, was what the Constitution demanded.

Choosing a method thus amounted to translating the Constitution into mathematics. Before “code” was law, math was law. But who was best positioned to decide the right way to make that translation? The economists and statisticians had their say and sided with Huntington. When the question of the apportionment surfaced in Congress again in 1926, the advocates for both sides began fresh campaigns to cultivate allies. Huntington and Hill worked with the Cornell economist Allyn Young to gather letters of support from a mathematically minded elite. Young compiled the letters into successive circulars that he forwarded the House Census committee and other leaders. A 1926 circular included testimonials from a business school dean, a math department professor, a life insurance actuary, and the nation’s leading biometrician. The list of supporters had grown in 1927, featuring prominent mathematicians from MIT, Columbia, Berkeley, Dartmouth, and Harvard. The mathematical community had converged on a consensus position—they said that equal proportions and the geometric mean were mathematically right. As Allyn Young put it: “as far as I can see, on Logical and mathematical grounds the method of equal proportions is the only right method.” Many took a further step too, equating being mathematically right with being simply right.

Willcox responded with his own circular letter in 1927, one that gathered the opinions of political scientists and constitutional law scholars. That group backed away from the claim the constitution allowed only one true method. But while no one method was mandated, they thought major fractions was better than the alternatives—it’s chief advantages were its relative simplicity and its accordance with established precedents.

Willcox and Huntington pleaded their cases in Congressional hearings in 1927 as yet another Congress had turned its attention to the failure of 1921 and tried to figure out what to do about it. Members debated whether to enact a reapportionment right away based on a 1920 census that many still believed to be fundamentally flawed or whether to wait until after 1930’s count. They also began seriously considering a “ministerial apportionment.” Such an apportionment (apparently suggested by Willcox) would put the task of allocating seats in the hands of the executive branch—the Secretary of Commerce or the President—who would use a prescribed method to make the apportionment based on the census results. That amounted to making the apportionment more or less automatic, which could only happen if officials responsible for it had a clear and stable method for determining the apportionment. It mattered deeply to Congress’s new plan that there be a method, but Congress appears to have cared less which method.

In March 1928, Hill lamented to Huntington: “At present hardly anybody knows that there is any question of method, and even Congress looks upon it as more or less academic.” Hill wanted to press further on the point that Willcox’s major fractions methods disadvantaged small states, seeing a political advantage there. Their colleagues began letter writing campaigns in favor of equal proportions. They attacked Willcox for his insistence that “the only way to get this bill through is to ignore altogether the practically unanimous opinion of statisticians and mathematicians on this highly technical question.” Huntington, for his part, practiced a politics of exhaustive explanation. He churned out papers, reports, and letters—writing and sending copies of works to everyone he possibly could. Huntington was determined win Congress over to the absolute rightness of equal proportions.

The methods controversy had played a part in killing the apportionment of 1921 and it seemed poised to play that role again at the end of the decade. States that stood to lose representatives had little interest setting up any fair apportionment system—the methods fight added more noise, and more cover for those intent on avoiding a proper reallocation of power. Huntington and Hill had believed that they could settle the matter with science. But they could not. No matter how clear the consensus among mathematicians, it could not control Congress, and Willcox could and did reasonably assert a counter-consensus from equally talented scholars in law and politics. As Alma Steingart has put it, “Both of them argued that their method represented the fairest solution to the problem of apportionment, but as their dispute wore on, it became clear that fairness was a slippery concept indeed, with more than one definition.”

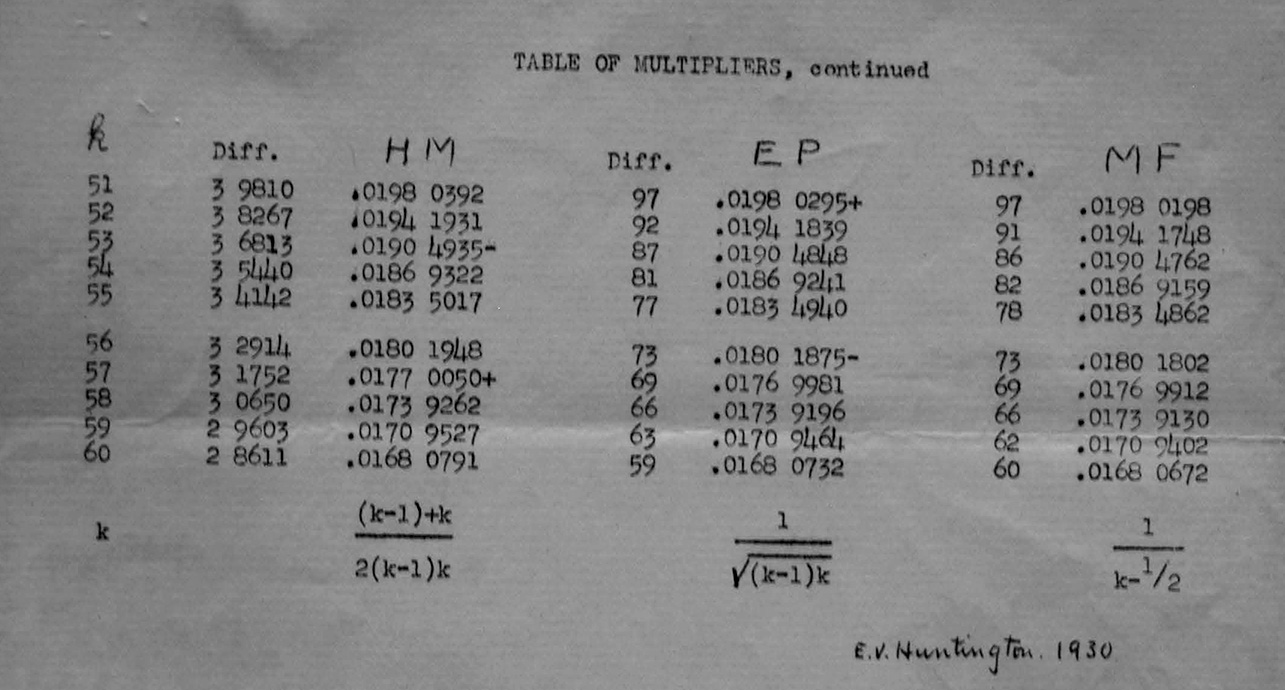

In the end, the apportionment problem could only be overcome by political will and acumen. Both the will and acumen came in the form of a Grand Rapids newspaperman, Arthur Vandenberg, who entered the Senate determined to win for Michigan the House seats (and electoral college votes) that it had been denied for the preceding decade.

It took Vandenberg a couple tries to corral his fellow Senators, and he had to hold the 1930 enumeration hostage in the process—he put a new plan for ministerial apportion in the same bill for the 1930 census. Congressmen who wanted the privilege of doling out thousands of plum patronage jobs to enumerators through the census had to fall in line and pass an apportionment bill.

Vandenberg’s bill charged the President with delivering to Congress a list of how many seats each state was due based on the results of the 1930 census. It instructed the President to apportion seats using the “method used in the last preceding apportionment” and for “the existing number” of House members—Vandenberg believed this left it more open for Congress to change either the apportionment method or the size of the house in the future, and more importantly it removed those contentious points from the letter of this “decennial stop-gap” legislation.

Vandenberg had little patience for the scientists or their controversy. The whole debacle struck him as an example of “how scientists can become so absorbed in their own specialty that they miss the main chance.” A few days later he expanded this line of thought to the Census Director: “The more I study this problem and the more I correspond with the rival mathematicians,…the surer I am that this need for permanent legislation will never be answered if we permit the contemporary problem to be clouded by this incidental quarrel over ‘methods.’“ Throughout 1929, Vandenberg begged and pleaded with the combatants to pause their conflict and stand together on the principle of apportionment. Not surprisingly, Hill—who had stood for that principle back in 1921—went along. But no one knew if Huntington would be willing to relent.

The historian Charles Eagles in his thorough history of the legislative battles over apportionment in the 1920s was as perplexed by Huntington’s eventual silence as his contemporaries were astounded. By Eagles’ telling, a Senator—upon hearing from Vandenberg that the statisticians unanimously supported his bill—“shouted ‘Mirable dictu!’” Eagles then noted parenthetically: “for unknown reasons Professor Huntington remained silent.”

The archival record reveals a coordinated campaign to keep Huntington quiet. Vandenberg courted Huntington assiduously, writing almost daily pleas beginning in mid-March 1929. “I am sure you will agree with me,” he wrote, “that the paramount thing is to get re-apportionment—regardless of the method used.” But Huntington did not agree. After Vandenberg won Hill over his side, Vandenberg deputized the Census Bureau official to rein in the Harvard mathematician. “I assume from our recent telephone conversation that you contemplate a ‘private argument’ with Professor Huntington,” wrote Vandenberg on 1 April 1929. “More power to you in that direction!” Even then, Vandenberg did not believe Huntington could be bridled. But Hill knew his man.

He appears to have sought to convince Huntington that the problem came down to politics, rather than science. He told Huntington that the New York delegation refused to vote for equal proportions (since it might deny them a seat) and so the bill had to stick with the last method used wording to get the bill to pass at all. Since Hill knew that Huntington could not have seen himself as being a political actor, Hill appears to have silenced his colleague by claiming that only politics were then in play and no science at all.

After the fact, when Vandenberg’s bill had finally passed and some apportionment was finally guaranteed, Huntington lashed out at the Senator. His feelings were hurt. Vandenberg had made a crack about the “busy Harvard mimeograph” and Huntington (correctly) read this as a sign of Vandenberg’s irritation. As I sat in the National Archives and pieced through the hundreds of mimeographed pages sent by Huntington (which were only a sample of all those he actually sent), I could not help but think that Vandenberg had a point: the mimeograph must have been exhausted! But Huntington—who we should remember wrote the letters begging for delays in the House and Senate in 1921 that justified killing the apportionment in the first place—refused to accept any responsibility. “It is inconceivable to me,” he wrote “that any proper legislation can be hampered in any way by such impersonal and colorless things as correct mathematical facts, and I decline to be classed as an obstructionist, either wittingly or unwittingly, of any legislative program.”

Huntington further declined to relinquish any control over how his method should be either calculated or understood during the crucial juncture when the Census Bureau developed its organizational machinery for the new “automatic” apportionment.

The war of the quotients ended. But the muddle of the multipliers and the division over divisors persisted.

Huntington insisted throughout the 20s and beyond on interpreting the competing methods of apportionment in terms of “tests.” A test of a major-fractions apportionment would show that shifting a seat from any one state to any other state would result in increasing the absolute difference between each individual’s share of representation. A test of an equal-proportions apportionment would show that the shifting a seat from one state to another would increase the proportional difference in each person’s share of representation or in the size of a state’s average congressional district. Huntington had proven mathematically that his method always led to an apportionment that passed that test—and it was for him the soul of equal proportions.

That was why, in 1928, he had dismissed out of hand a suggestion made by the Census Bureau’s top mathematical mind: Elbertie Foudray. “Miss Foudray” was the person who Joseph Hill turned to when the math got too difficult for him. That happened a lot when it came to apportionment. As a result, apportionment records in the archives are littered with markings like this one:

At the height of the war of the quotients, Foudray proposed that the Census Bureau change its methods for calculating apportionment distributions. It had up to that point used two different kinds of approaches, a different approach for each competing method. For Major Fractions, the Bureau used something called a “sliding divisor” or just a “divisor,” which was a number divided into each state population such that the result was an integer and then some decimal fraction. If that fraction was 0.5 or higher, the integer was rounded up—otherwise it was rounded down. For example, if New York’s population was divided by the divisor and the result was 42.56, it would get 43 seats in the apportionment. This was the way Walter Willcox had always done it since inventing Major Fractions. This was how a divisor approach worked.

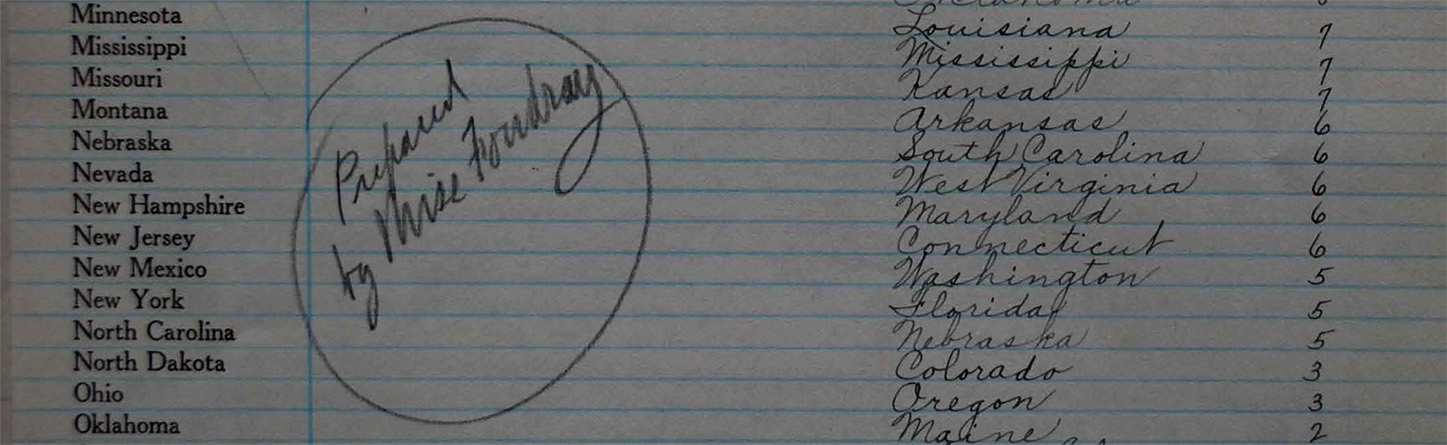

The Census Bureau, following Huntington’s protocols, had instead used a system built on multipliers. Huntington started with all 48 states and their populations, then multiplied each by a geometric means of 1 and 2, 2 and 3, 3 and 4, and on and on. He wrote the resulting products on a cards along with the name of the state and then put all the cards in order of the numbers written on them. This process created a “priority list.” All one had to do was go in order through the cards handing out seats to the states written on each card until all the seats had been handed out. That was it.

Elbertie Foudray proposed calculating both apportionments using a divisor method. She realized that it was possible to choose a divisor and divide it into each state population and then round up when the decimal fraction after the integer exceeded the geometric mean. This was how I described the method earlier in this post, in fact. Foudray took her insight a step further, asserting a fundamental similarity between major fractions and equal proportions. In fact, she said, they were also similar to three other possible apportionment methods that involved a divisor—one of which rounded all the fractional decimals down, one of which rounded them all up, and one of which rounded up when the fractional decimal exceeded the “harmonic mean” (which is another even weirder kind of average). Foudray concluded: “it is readily seen that these methods differ only in their tables of constants.” That is, the only difference is what decimal values are the cut-offs for rounding after using the divisor.

Hill sent Huntington the proposal—because, again, Hill didn’t really have the mathematical ability to evaluate Foudray’s work—and Huntington shot it down. His objections strike me as peculiarly weak. He picked on small mistakes, or invented misunderstandings. He closed his judgment by saying it was better to stick to doing it his way: “To construct a priority list according to the regular method…cannot take any great amount of time if you use the table of multipliers with additive differences which are supplied in my paper, and write the results on cards as there suggested….all in all I doubt whether Miss Foudray’s plan would effect any substantial saving in time, even if it were correct.”

That was in 1928, as the methods battle raged. In 1930, the automatic apportionment regime had begun under a kind of truce. Major Fractions would be the default method of apportioning seats, but the President had to transmit to Congress calculations for both methods. As the 1930 census—begun on April 1—completed its count, the Census Bureau turned in October 1930 to the task of calculating apportionments.

This time, it was Census Director Steuart who forwarded a new version of Foudray’s proposal for Huntington’s review. “Miss Foudray is our expert mathematician and has given the apportionment business a great deal of attention,” explained Steuart. Huntington again judged it “more complicated and probably no more expeditious” than using cards and multipliers to generate a priority list. A few days later Huntington wrote again, this time sending a set of tables of printed multipliers that the Bureau’s human computers could use in doing the apportionment calculations the right way (his way).

Joseph Hill and the Census Bureau appear to have been won over to Foudray’s theoretical position. Hill composed queries to go out to Huntington and to Willcox forcing them to admit that the multiplier and divisor methods were essentially interchangable. Hill asked Willcox: can the method of major fractions be accomplished just as readily using a table of multipliers and a priority list as through using a divisor? He asked Huntington: can the method of equal proportions be satisfied through the use of a divisor instead of multipliers and a priority list? The responses were both telling and predictable. Willcox, who was never so doctrinaire or dogmatic, said simply: yes. Both approaches worked. (Although he hoped it would be presented to Congress as a divisor method for consistency’s sake.) But Huntington resisted. He admitted that a divisor method could yield the correct result, but this—he insisted!—was only a “mathematical curiosity.” After his typed response, Huntington wrote by hand one more exclamation: “I wish to point out emphatically that these paragraphs are of purely academic interest, since the quickest way to find the proper division to use in order to secure a House of any predetermined size is to go through the regular process of computing a priority list.” Hill refused to give in this time, writing “I do not believe that we have any right to say to anybody you must do it this way and not that way, if that way will produce the same result.” Besides, he continued, Huntington’s method really did not seem to be any easier or faster to him.

Over the next decade, Foudray—and later Morris Ullman—continued the theoretical investigation of apportionment methods, producing fascinating (and beautiful) charts along the way.

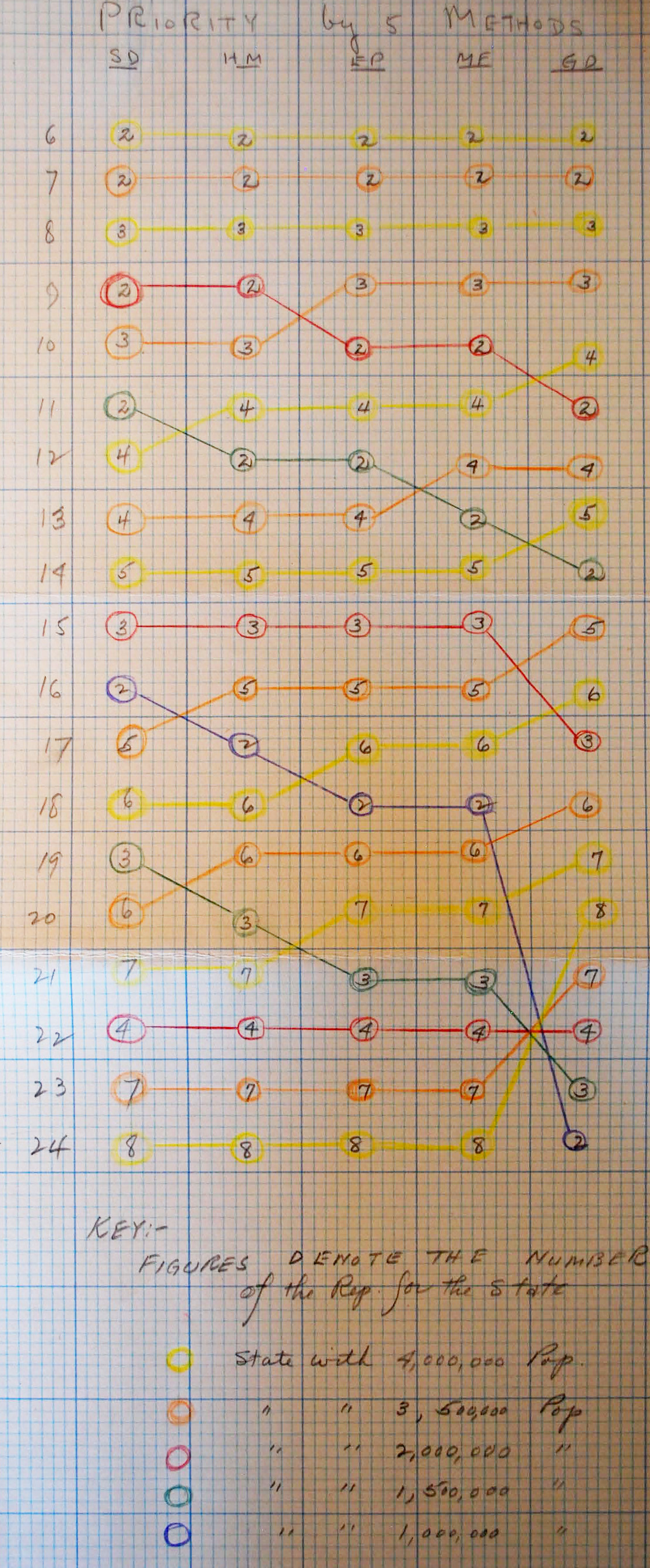

This one, titled “Priority by 5 Methods,” depicts a series of hypothetical apportionments. The five methods referred to in the title are “smallest divisors” (SD, which just rounds every fraction down), “harmonic mean” (HM), “Equal Proportions,” (EP) “Major Fractions,”(MF), and “Greatest Divisors” (GD, which rounds ever fraction up). The author of this chart has invented five hypothetical states, the great states of Yellow, Orange, Red, Green, and Blue. Yellow is the biggest state, with 4 million residents, and Blue is the smallest, with only a million. Each row of the chart represents a different sized hypothetical house, beginning with a house of 6 seats. (Since the constitution guarantees each state a House seat, the first five seats are allocated one to each state.) The chart shows that Yellow State gets the sixth house seat, no matter which method is used. Similarly, in a house of 7 seats, Orange State gets the new seat regardless. The “2” in the Yellow and Orange circle indicates that both states now have two seats. Yellow, because it is huge, gets its third seat next, with all methods agreeing. And then we find our first disagreement with methods—some drama finally!!—with the 9-seat House, where Red State gets a second seat by virtue of the the two methods that are kindest to small states, while Orange State snaps its third seat by the other methods.

In this hypothetical situation, Huntington and Willcox would have no reason to quarrel until seats 12 and 13 come up—that’s where Equal Proportions and Major Fractions disagree for the first time.

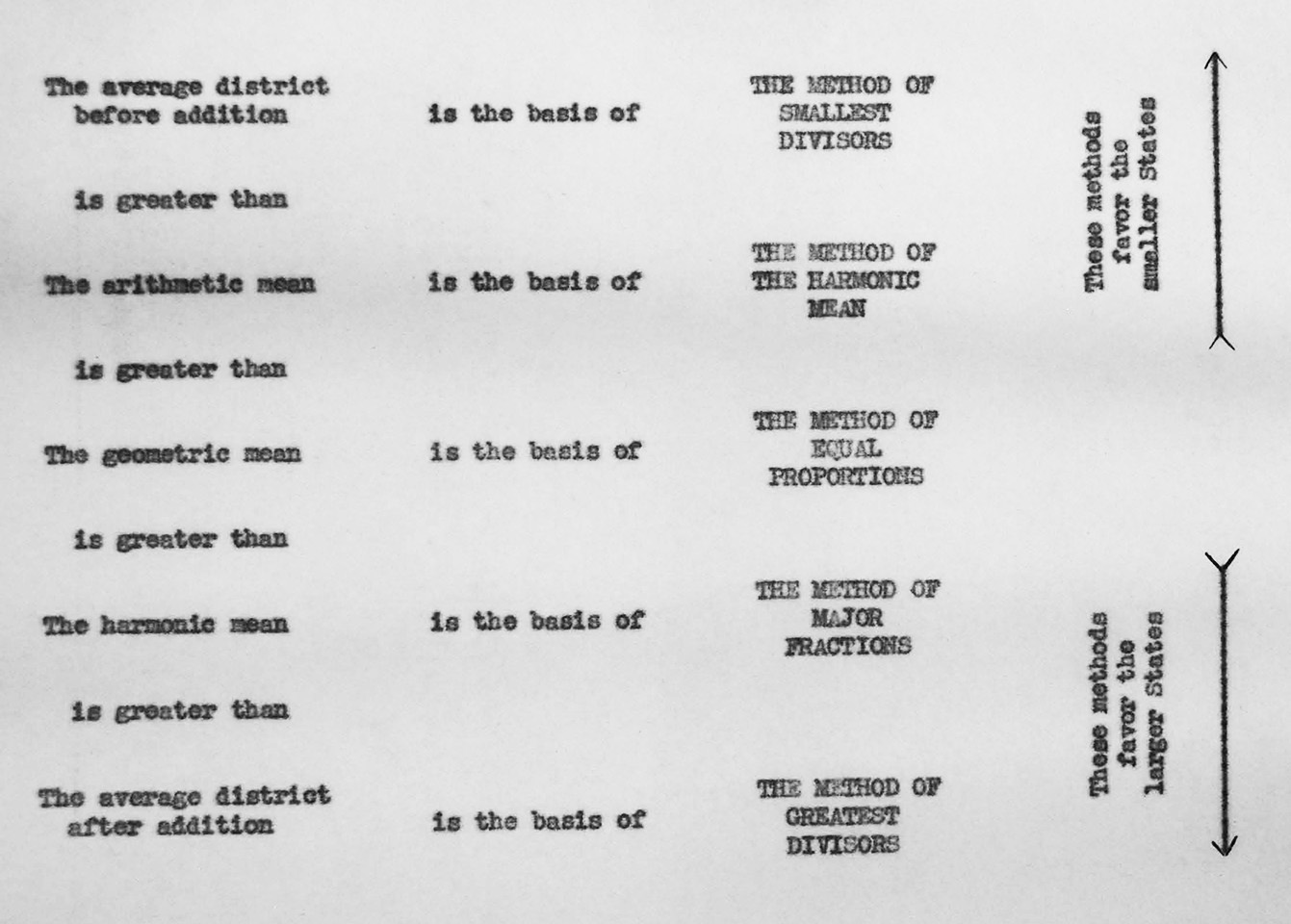

In July 1940, Elbertie Foudray endured the indignity of watching the Census Bureau hire a man to do the job that she had always done, a man who would be her boss, a man I must assume she trained. (Even better(?!), that man appears to have also had a specialty in parapsychology and the study of extrasensory perception!) It must have been sometime after his first day of work August 15, 1940, that the new Associate Actuarial Mathematician Thomas N. E. Greville made this chart to laying out the differences among the five apportionment methods.

I wonder if Foudray laughed at Greville’s blunder, mixing up the arithmetic mean and the harmonic mean on the left-hand side. He wasn’t dumb, and he knew the difference. Indeed, he got the order right in the center column, but I hope that Foudray might have taken some pleasure in the typo regardless.

Both of these charts, notably, situate “equal proportions” in the middle position. That was hardly an accident—the point was to make equal proportions seem like the unbiased, compromise position. Huntington pioneered this framing in 1928 and his acolytes in the Census Bureau followed suit. As the Balinski and Young argued in 2001, one could make just as ready a case for placing major fractions in the compromise position since it sits smack in the middle of all possible “divisor” methods. Balinski and Young, in fact, make a very convincing case that the U.S. ought to adopt the major fractions method again. (Perhaps this weakness in his intellectual defenses was another reason that Huntington so resolutely objected to treating Equal Proportions as a divisor method.)

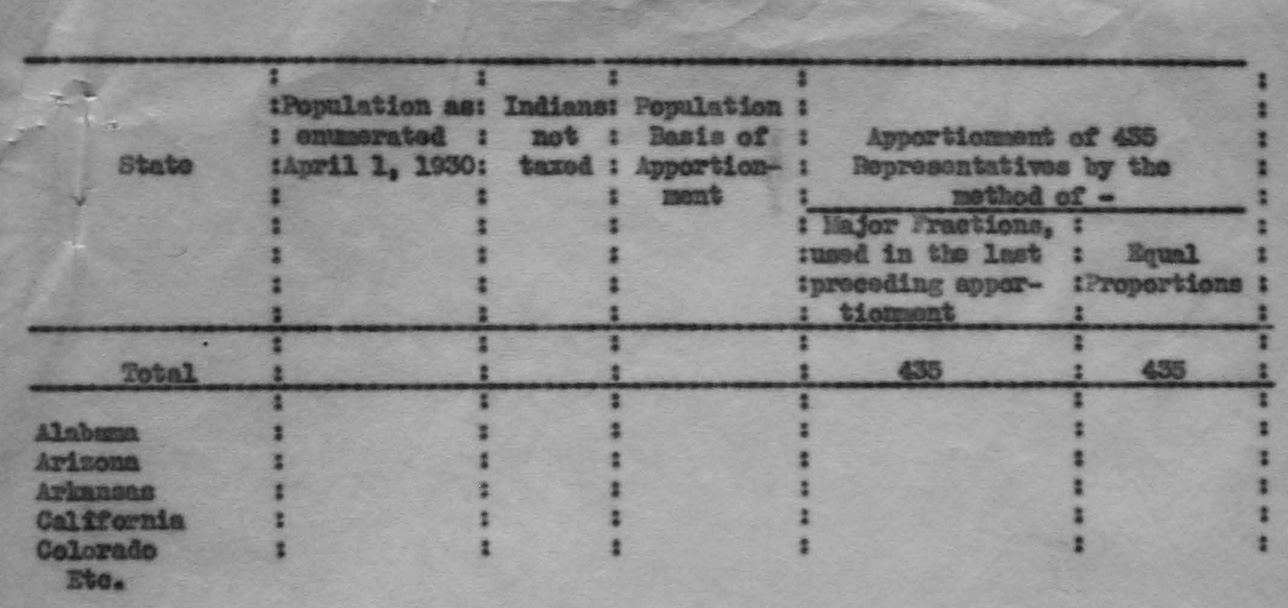

Much in this new automated system would be new, including the form by which the Census Bureau would prepare the apportionment figures and pass them through the President to Congress—inaugurating the tradition of “announce and transmit” that has endured since.

Bureau officials sought—and received—Huntington’s approval for their draft table. This is what it looked like:

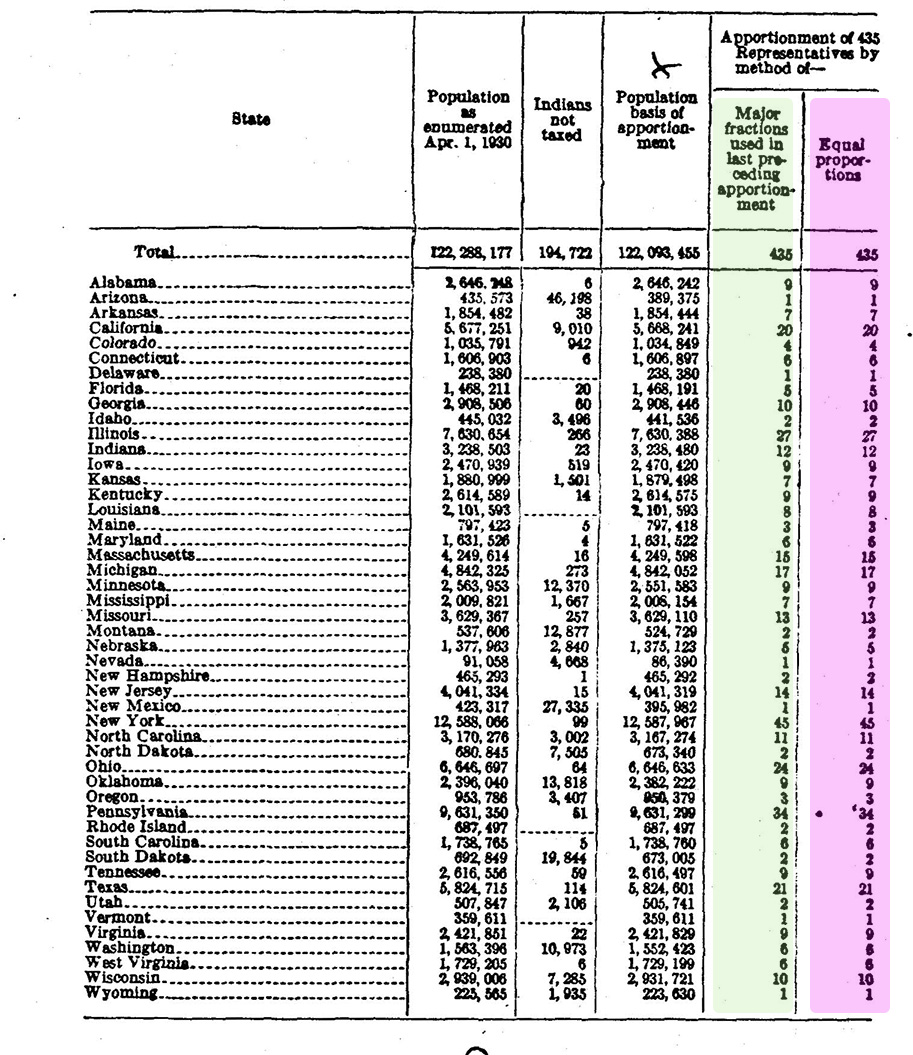

In November 1930, Huntington and Willcox both worried a great deal about the numbers that would populate those columns. Huntington, with his strong alliance to Hill, got more frequent updates than Willcox. But both appear to have been surprised when the Census Bureau announced its numbers officially. As Steuart informed Willcox: “There is a striking coincidence in that the distribution of 435 Members gives the same number to each State, no matter which method is used.” The apportionment by major fractions (highlighted in green below) matched exactly the apportionment for equal proportions (in purple). Willcox must have been elated: if the two methods concurred, there was little reason for any member of Congress to a champion a bill to change the apportionment method.

Hill advised him that given the circumstances no hope of a new bill in 1931 remained. Huntington cursed fortune and the size of the House, writing: “the number 435 (darn its soul!)”

Still, against the wishes of his Census Bureau allies and against the express desires of Congress, Huntington fired up the mimeograph—just in case, and because this was what he did. Huntington sent each member of a Census Committee a copy of a new essay called “The Choice Before Congress.” Congress chose to ignore him.

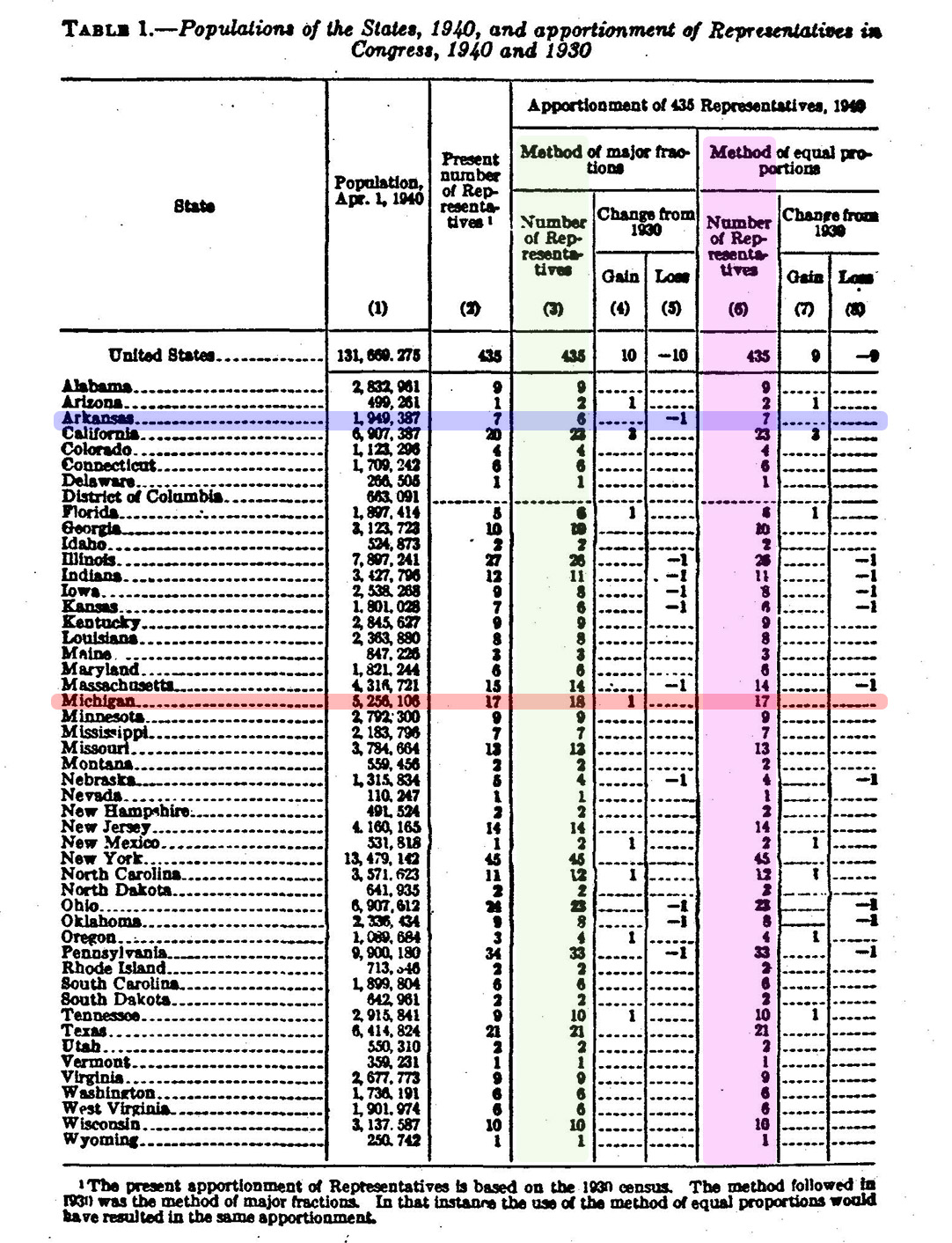

He tried again after the 1940 census, and this time luck played on his side. The apportionments differed for the two methods for one pair of states. Arkansas (in blue below) lost a seat by major fractions that Michigan (in red) gained.

Joseph Hill had died in 1938, leaving his successor Calvert Dedrick and the young Morris Ullman to continue in his place. Dedrick allied with Huntington, at least in part out of loyalty of Hill and his memory. As Huntington’s ally and so a proponent of equal proportions, Dedrick wrote a Census Bureau essay called “Some Essentials of Apportionment Methods.” In it, Dedrick imagined a conversation between a Arkansan and a Michigander, the first arguing for the validity of the method of the harmonic mean—which assured Arkansas kept its seat—while the second argued for major fractions, and so Michigan’s increment. “Let us now introduce a mathematician,” wrote Dedrick, around the same time that Ullman followed a mimeographed map to visit the mathematician Huntington in his mountain cabin. Dedrick’s imaginary mathematician—cast as an impartial expert—did not choose a state, but rather a method: equal proportions. It was only of incidental note that Arkansas benefitted from this judgment.

The automatic apportionment act did its work according to the method of major factions. But this time a representative from Arkansas had reason to fight for a new bill, one that would swap in equal proportions for major fractions. Huntington, Dedrick, and Ullman stood ready to help. It did not hurt that Willcox had abandoned his defense of major fractions to advocate for the method of “smallest divisors,” the method most favorable to small states. Dedrick, as a precaution, also did his best to quiet Huntington. “If I may be perfectly frank with you,” he wrote, “and I feel that I can, I would advise that you not send further mimeograph letters to members of the Committee on Commerce….I feel that effects of this type on your part will not further sympathetic understanding by the Senate of the essential issues of the problem of reapportionment.” As the Dedrick saw it, the Harvard mimeograph was unlikely to help and almost assured to annoy.

The bill for equal proportions passed and was signed into law. Most contemporary observers—and historians since—have credited political calculation for the change. Arkansas, the logic went, voted solidly Democratic, while Vandenberg’s Michigan usually picked Republicans. Roosevelt and his Democratic Congress picked the method that secured them an extra seat and an extra electoral college vote.

Equal proportions won. Dedrick exclaimed to Ullman “Dr. Hill is vindicated!” Huntington received a pen from Roosevelt that the President had used to sign the bill into law.

Ever since, the Census Bureau has calculated and printed only one column of official apportionment results. The method of apportionment could still be changed by Congress at any time, but no one calculates the major fractions apportionments (or other alternatives) and no alternative appears in the President’s message to Congress. Those silences around method sealed the victory that Hill, Dedrick, Ullman, and Huntington worked for so long to achieve.

The end of the methods controversy sealed another victory too, the victory of those intent on fixing the size of the House at 435 seats—including Huntington’s longtime adversary Walter Willcox. For Willcox, even as far back as his speech to economists in 1915, the fight for major fractions began with a desire to create an apportionment system that could be made automatic. An automatic apportionment would in turn make it easier to stop the growth of the House. If Congress had to set the size of the House ahead of the census count, there would be no chance for political horse-trading, no compromises where powerful representatives voted to increase the size of the House to save a fellow member’s seat. Willcox gave up the fight for major fractions in 1940, but his triumph had been great. The fight over method had contributed to a terrible miscarriage of Constitutional justice that allowed white, native-born Americans to seize and hold on to undue power for a decade. But the final result was just what Willcox and the scientists in the Census Office had dreamed of: a stable House apportioned by an indisputable algorithm. A century has passed and the U.S. has more than tripled in population, while adding two new states, but the House of Representatives remains the same size as it was, apportioned every ten years (so far) by the method of equal proportions.

This post is published under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license by me.