The (Statistical) Battle of New York

The 1920 census produced reasonably good data. It was, at the very least, not exceptionally bad. This is a crucial point and one we must accept from the start.

Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol opens with the line: “Marley was dead: to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that.” And Marley’s long-time business partner, Ebenezer Scrooge, knew that Marley was dead. He signed the burial register. “Old Marley was as dead as a door-nail.” The ghost story that follows depends on everyone accepting that fact. Marley’s visitation on Scrooge only becomes significant, when we acknowledge that Marley is dead.

So too, the story I am telling in these recent posts (and especially the one you are now reading) only matters if we accept the viability of the census of 1920. Whatever else would happen later, it was not (in 1920) a failed census.

It is far from clear what would constitute a failed census, a census too deeply flawed to be believed or used. It would have been even less clear in 1920.

The Census Bureau did not yet have a rigorous method for evaluating the completeness of its counts in 1920. Since 1950, each census has been followed by another smaller survey of a sample of households, the purpose of which is to gauge how many people were missed by the actual enumeration. The Census Bureau supplements this “post-enumeration survey” with what is called “demographic analysis.” In that process, an analyst compares the results of a census to a population estimate that begins with the prior decade’s census count and adds to it births and immigrants while subtracting deaths and emigrants. Both were cutting-edge techniques in 1950. Post-enumeration surveys depend on methods of statistical sampling that were invented in the early-mid-twentieth century and only first used at a nation-wide scale in the late 1930s. Demographic analysis, though an older method, was only so reliable as the system for registering births and deaths that it depended on. That system only became consistently reliable for every U.S. state in the 1930s. For all censuses before 1950, we can find in the archives anecdotes and makeshift analyses. Such work has not satisfied historical demographers, who have in the last half century worked to more systematically evaluate the completeness, coverage, and accuracy of earlier censuses.

They have discovered a consistently leaky statistical apparatus. Richard Steckel in 1991 argued (from a review of existing literature) that it wouldn’t be unreasonable to conclude that mid-19th century censuses undercounted the population by at least 15%, and maybe even up to 35%. Steckel cited a study from 1963 showing that on average 7.2% of children aged 0 to 4 went uncounted between 1880 and 1950, where the underenumeration rate for the 1920 was neither the highest nor the lowest. In a 2013 analysis, J. David Hacker estimated coverage rates for native-born whites in the nine censuses that took place from 1850 to 1930. The 1880 census turned out the best, missing only 3.8% of that population. The next two best censuses—1900 and 1930—missed 4.8% and 5.1% respectively. The 1870 census was worst, landing at an underenumeration rate of 6.6%. The 1920 census tied with the 1850 census, failing to count 6% of native-born whites. It wasn’t a great census, but it was—by this crude measure—not exceptionally bad. The 1920 census was flawed to a rather ordinary degree.

But boy did it showcase its flaws with flair.

The flaws of the census had no greater spokesman than the supervisor for the count in Manhattan. Samuel J. Foley was a “machine” man, in the political sense. Born in Canada to an Irish father in the middle of the U.S. Civil War, Foley rose to power in New York through the immigrant-driven political machine that ruled New York: Tammany Hall. Tammany had placed him in the state’s assembly, in the state’s senate, and in 1920 it got him on the list to be appointed by the Secretary of Commerce to be Manhattan’s census supervisor. His job was to ensure that every person in his borough was counted, and the pride of the city was at stake.

Newspaper reports early on noted that Brooklyn was gaining on Manhattan and might in 1920 surpass its island neighbor for pre-eminence in the city. When Washington announced the initial census figures on 5 June 1920, Brooklyn’s figures came it at just over 2 million people, which represented a big gain from 1910. Manhattan kept it’s lead in the population race by a couple hundred thousand. But the real shock came in revelations that Foley’s Manhattan had not just grown slowly over the past decade. It had shrunk by just under 50,000 people. Many New Yorkers could neither believe or accept this result. They cried foul.

So Samuel J. Foley met a New York Times reporter on 7 June 1920 and “in the billiard room of the Murray Hill Hotel yesterday defended the count of the population of Manhattan.” The Murray Hill Hotel loomed over Park Avenue, its dark stone and balconied windows ornamented by a gleaming turret.

What went on in that billiard room? I imagine smoke from a cigar in Foley’s left hand. I imagine a snifter of brandy in the other. In fact, I very much hope that there was brandy—that would explain the interview that followed.

Foley began spinning out a yarn about the ways Washington had “hampered” his efforts. “One of the districts, he said, which was created at Washington for the purpose of having its residents canvased by an enumerator consisted exclusively of the Equitable Building.” This was funny because the Equitable Building, which featured two block-long towers that literally blotted out the sun, rented office space. No one could possibly live there. Silly Washington didn’t realize this. In truth, the Census Bureau’s geographer might not have known the building existed—it had only been finished in 1915. Foley also told the story of an enumeration district that only held a gas works and gas tanks. Such stories were not unique to Manhattan. On the very first day of the census, a Chicago reporter told the story of a young woman who came in from the cold with a red nose having spent an entire morning in her district searching for a person living in what she discovered was a lumber yard. A supervisor told the reporter of similar errors: “Why, one woman this morning found when she got to her district that it was mostly Jackson park, and there’s nobody lives out there but the life savers.” These were just par for the course of a nation-wide enumeration. “They’ll fix her up downtown, though,” explained the supervisor. Foley, though, interpreted the errors in Manhattan as a personal affront.

That may have also been because Washington had come to his doorstep. Everyone knew that New York City presented the “census takers’ greatest problem.” It was the biggest city in the entire world, and as Foley put it, “the people hop about like bees.” Of the 86,000 enumerators canvassing the country, more than 4,000 worked in New York alone. So, naturally, the Director of the Census Samuel L. Rogers went to New York on January 1 to kick-off the count personally. He detailed his assistant director, William Mott Steuart, to the city to oversee the operations. Foley did not appreciate the oversight.

He told the reporter that the Census Bureau had saddled him with a “red-headed expert.” All the photos I’ve seen of Steuart are black and white, and Steuart doesn’t have much hair to speak of in any. Here is one of those photos.

Maybe what hair he had was red. Or maybe Foley’s red-headed slur has some other connotations lost on me, like the disparaging uses of “redneck” today. Later in the interview, Foley called Steuart (whom he never named, and did even appear to know the name of) a “red-headed Southerner, very much out at the elbows.” Foley criticized him for not being cleanly shaven—more evidence that Foley channeled his rage at what little hair Steuart had. The reporter wrote that Foley “became very emphatic in his expressions” when talking about Steuart, and “occasionally paused over an epithet to suggest a compunction as to its publication.” But he barreled on anyhow, perhaps after pausing again for a sip of brandy.

The fight clearly had to do with authority. Foley said: “he came here under the impression that he was going to run the census here.” But Foley wanted it clear that he was in charge. He bragged to the reporter: “One day [Steuart] came rushing into my office, and I told him never to come in again without my express orders, and that, if he did I would throw him over the partition.” Foley did not appreciate Steuart’s bureaucratic sensibilities. He said that Steuart had secured money from Washington to hire 30 clerks, but then let them all go later. “Can you imagine a Tammany Hall man laying men off when he could get work for them to do?” he asked. We can only imagine what Steuart thought of Foley, and what he thought when Foley’s comments reached him in Washington.

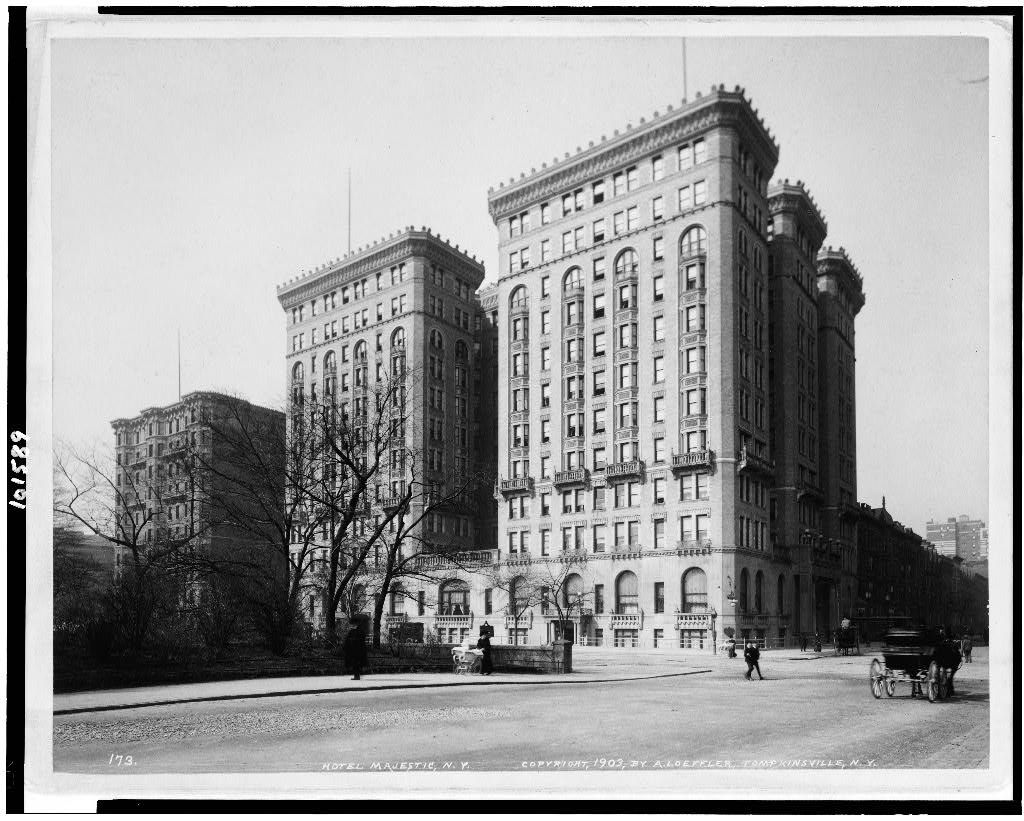

Foley’s primary job was to oversee Manhattan’s enumerators. About Foley’s attitudes toward them, the reporter wrote: “While defending his enumerators as a body, Mr. Foley said that some were very bad.” He told of one enumerator who he determined had missed 1,000 residents. He said one enumerator missed the Hotel Majestic entirely, a multi-towered skyscraper that loomed over Central Park, and was impossible to miss.

Having described the absurd, Foley moved on to the corrupt. There was fraud among his census takers, he said. There where those who took “names off the bells in the front hall” and then just made up the rest. “Some of them manufactured their lists in the back rooms of gin-mills,” claimed Foley, maybe after another sip of his own drink. “ knew this to be the fact, though I could not get the absolute proof of it,” he continued. He did try to catch fraudsters, but failed in that too. Ultimately, he settled for spreading unsubstantiated rumors about his employees in the paper of record.

At this point, it’s worth recalling that Foley set out to defend the count of Manhattan. Imagine if he had tried to defame it!

Foley tried to dig his way out. “I have emphasized the obstacles and troubles we had,” he said. Then he gave the census results the most half-hearted of endorsements, “but on the whole, those figures are right, and certainly as near right as they be made under the circumstances.”

After the Manhattan totals were announced, another New York Times employee got out a telephone book and started calling Browns, Gillespies, and Smiths at random, along with a few people with other last names. Of 17 people reached over the phone, only 11 said they had been counted by the census. Edward Gillespie said that he had been missed. No enumerator had come to his door. His name appeared in the newspaper in a list of those contacted, as evidence of the census’s flaws.

So did Joseph Stirling’s name.

Census Bureau officials in Washington tried to calm the waters. There was no need to panic. People often don’t remember being counted, or don’t realize that someone else in their household provided their information. Director Rogers assured New Yorkers that the Bureau was ready to take the information of any “John Doe” who had in fact been missed and fix the error. More generally, Rogers said he would cooperate with any “responsible body” in New York City toward “making the most perfect work possible of the census in this city.”

A few different bodies stepped forward to claim that responsibility.

New York’s mayor appointed a group. The health commissioner chaired it, alongside the commissioners of police, public welfare, tenement houses, fire, and the president of the Board of Education. That committee would organize a “police check.” In the place of the ordinary citizens who conducted the actual census—those who Director Rogers called the “many school teachers and young men and women of intelligence who rendered splendid service”—the city would send out its uniformed police officers to about 100 enumeration districts across Manhattan. That count, I imagine, might have been more memorable for those surprised to find cops asking questions at their doors.

From the start, the mayor’s committee came out on the side of census skepticism. They gathered up records that could speak indirectly to the dynamics of the city’s population. They analyzed health board records of births and deaths. They looked at figures on the numbers of school children. These administrative records pointed to a growing population, not a shrinking one. If the numbers didn’t point to large enough growth, as was the case with the school records, the committee squinted a little, and reasoned that those figures were artificially low, since they did not count all the children who now attended Catholic parochial schools. They were determined to discover an undercount of the city, and they broadcast their doubts about the census as loudly and widely as they could.

By contrast, the “New York Census Committee” (NYCC) stood publicly in defense of the census from the start. Its members included prominent academics, church leaders, social reformers, and businessmen, all of whom had been working with the Census Bureau from the start of the count to create a new, fine-grained statistical unit of geography: the “census tract.” When the controversies over the Manhattan figures broke, the NYCC assigned a group to write a investigate, led by the Columbia University statistics professor Robert Chaddock and the statistician for the life insurance behemoth Metropolitan Life, Louis I. Dublin. But Walter Laidlaw, a statistician for the New York Federation of Churches, stepped forward right away as the most vocal advocate for the census.

Laidlaw issued a statement saying that he pored over the count data for Manhattan for three days. He declared that “the 1920 census announcement for New York City as a whole and for Manhattan Borough as a component is puncture proof.” Those who said that Manhattan had been undercounted had an agenda. “Realty agents may rage,” he wrote, speaking of the prominent property interests who used growth figures to buoy home prices. Others wanted census figures to be higher so as not to contradict their own statistical systems, he guessed: “some city departments imagine a vain thing for the verification of their records.” But Laidlaw felt confident that the numbers were right.

The count had not gone perfectly, he admitted. Some people had been missed in January. But they had nearly all been found in the “mopping-up” process in February—a campaign that plastered churches, movie theaters, and schools with the question “Have you been counted by Uncle Sam?”, directing those who hadn’t to the offices of Foley and his fellow supervisors. It might still be that the New York Times or the Mayor’s committee would find unenumerated individuals, but they were the exceptions—not the rule. What is “one or even 1,000 among 2,000,000?,” asked Laidlaw. It was clear to him that “more pains have been put upon this follow-up process in Manhattan, in this census, than in any other since 1890.” The effort put into the count assured its validity.

Samuel Foley, who was always at the ready to render back-handed compliments to the census within the hearing of reporters, made a similar point. He said “that he did not contend that the Manhattan census figures were complete.” He only argued “that the work was as well done as was possible.”

The police hit the streets in late June. They visited 113 Manhattan census districts out of the total of over 1500 in Manhattan. (The highest numbered district in Manhattan was 1538, which covered passengers and crew on ships docked in the Port of New York.) The lists generated by the officers carried the names of 4,283 people who did not appear on Federal census records. (It’s not entirely clear, but it seems that the Mayor’s committee gained access to the census records directly, which seems to have been legal under the confidentiality law of the time. The legislation authorizing the 1920 census included a guarantee that individual records would not be published or used against the interests of individuals, but gave the Census Director discretion to furnish records to governors or courts, and so perhaps to mayors too.) The police check discovered a little over 4,000 missing people. It had covered a bit under 10% of the borough’s enumeration districts. So the committee extrapolated that over 50,000 people had been missed in Manhattan. That was enough. It gave Manhattan a small gain in population for the decade, instead of a small loss.

The Mayor’s committee filed a report that emphasized these “startling discrepancies” in “by far the greater part of the districts.” A few months later, when the head of the House Committee on the Census starting talking about a different sort of one-day census, a census that worked more like the military draft registration, the example of New York was on everyone’s minds. As a Times article reminded its readers: “The tests made by the Mayor’s Committee in June indicated that the population of selected sections of Manhattan was greater by 2.07 per cent. than the Federal Census had showed.” The Mayor’s committee recommended a new census of Manhattan to take place in October or November. But it doesn’t appear to have ever happened.

The Census Bureau probably did not feel too bad about a 2 percent undercount. They made no public remarks.

The Bureau had revisited the cases of the men who the Times had claimed were overlooked.

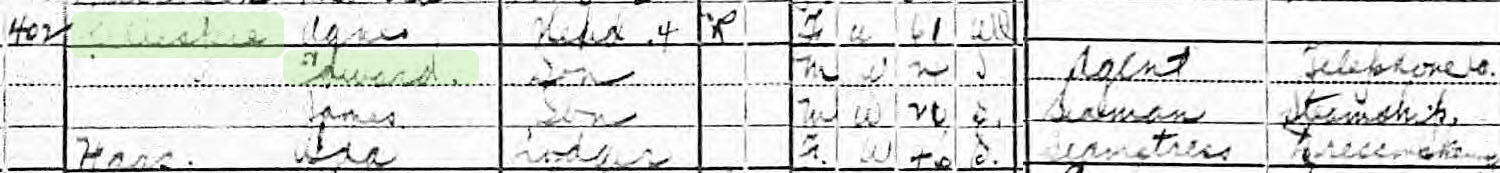

They found Edward Gillespie in the enumeration portfolios. An enumerator named Robert B. Murphy had come to Gillespie’s mother’s apartment at 443 W. 47th Street on 9 January 1920 and took down this information:

Gillespie wasn’t missing after all.

The case of Joseph Stirling was more complicated.

To begin with, the New York Times had misspelled his name. Stirling was really Sterling.

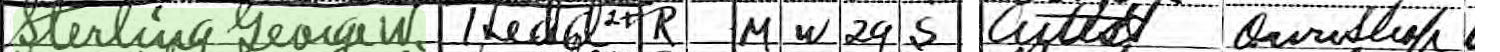

The Census Bureau looked in its records and discovered a Sterling living at 12 East 30th St. Here is the record, apparently entered by an office clerk named Joseph Benjamin during the mopping-up phase in February.

Sterling, George W.

Sterling, George W.?

Who was this Manhattan artist living on block filled with salesmen and artists?

According to the Times, he did not exist. “It was stated yesterday that the census taker had been in error and that no George W. Sterling lived there, but a Paul M. Sterling and a Joseph Sterling, both of whom were missed by the enumerator.”

One Sterling counted, one missed, but none properly identified. This was far from the hoped for census outcome. Yet from years spent trawling through census records I can also say such an outcome is far from surprising. These things happened in a count made by 80,000 enumerators tasked with counting over a hundred million Americans.

As I said, the 1920 census was not particularly flawed, but it showcased its flaws with flair.

While the census was not exceptionally flawed, it was pretty darn late.

The 1920 Census was the first (and last) to begin on January 1. The count was supposed to take two weeks in cities and a month in the country. It often took longer, but that doesn’t mean communities didn’t take the deadlines seriously. The Los Angeles census supervisor had a census resiste arrested on 13 January and threatened mass arrests to follow. Time was running out. A city council resolution lamented that “but a few days remain in which to complete the work of taking the census” and implored all citizens to cooperate.

Once a city (or other region) completed its count, the supervisor tallied up the number of individuals each enumerator counted (in order to pay that enumerator on a per head basis). The supervisor included that tally on a slip that accompanied the completed census sheets to be sent to Washington. There in the Census Bureau offices, clerks independently counted names from the sheets. The totals were then checked and reconciled. Everyone called this procedure “the hand count.” (More on hand counting here.) Washington D.C. and Cincinnati must have run tight ships—and gotten lucky. The Census Bureau released preliminary population totals for both cities on 21 February 1920. They commemorated the occasion with this photo. (Steuart stands on the far left, with Director Rogers next to him.)

The LA supervisor said he thought his city’s numbers would be available in a couple more weeks.

It really took months. The Census Bureau announced LA’s population on 9 June 1920, a few days after announcing New York’s data. But even six months in, not all the counting was completed, not all the numbers were out. The Bureau’s announcements through the end of June encompassed just shy of 66 million people. That left about 40 million waiting in the wings. The Census Bureau blamed the delay on the weather:

“The progress of the enumeration was materially impeded by the unusually severe weather conditions which prevailed in most of the northern states. Even in the south the enumeration was delayed by the torrential rains which occurred in many localities. As a result of these adverse conditions, the returns from the enumeration were not received at the Census Office as rapidly as had been hoped and expected.” But when September rolled around.

Writing now, locked in because of a pandemic, I keep expecting to see the Census Bureau in 1920 blame delays on the flu. After all, much of the nation had shut down in the prior year as the 1918 Flu burned through the population, coming again in 1919, and it still attacked some communities in 1920. There are hints of flu in the census record. Our friend Samuel Foley said that flu (or its threat) disrupted the New York count: “The epidemic of ‘flu’ upset us,” he said. “Some of the employees had it and others pretended to have it.” True to form, Foley managed to get in a dig at his census takers even in this case. The Census Director’s final report of 1920, written in late September, also made passing reference to “pandemics of influenza” alongside “severe weather conditions” as an explanation for why counts were delayed. But on the whole, Census Bureau officials don’t seem to have believed the flu had harmed the count.

The Census Bureau blamed bad weather publicly, but labor shortages were much more devastating. The official in charge eof the agriculture census, William Lane Austin, resented the way the Director kept saying the winter storms caused delays. It had been Austin’s idea to fun the census in January, so he took the comments personally—and he also thought they were faintly ridiculous. In a September letter, Austin reminded his colleagues that bad weather didn’t stop schools and the mail from running during the winter. There were, he said, only one or two districts where severe weather really caused a substantial problem. Austin offered two alternative reasons for the slow census. For one, he noted that “wages and salaries in all other lines of business had increased very materially and that living expenses had gone up correspondingly,” but the Census Bureau was paying the same rates to enumerators that it had a decade earlier. Beyond the issue of wages, Austin noted that “during the recent winter it has been impossible to employ help of almost any kind for reasonable wages in all sections and in all industries of our country.” For this he blamed “the general condition of unrest and dissatisfaction, generally among the people of the United States which followed probably as a result of war conditions.” The problem wasn’t the weather—it was America’s abnormal condition.

On October 7—10 months after enumerators knocked on their first doors—the Census Bureau announced the U.S. population: 105,683,108. But even it was provisional: “The figures are subject to revision,” wrote census official Joseph A. Hill, while adding that “there is not likely to be any material change in the total.” That number would still be revised slightly before Congress received the official state counts. Hill had his own explanation for why the Bureau announced the total population a little later than usual:

The announcement of the total population of the country was delayed in some degree by the unusually large number of complaints and demands for a recount coming from communities where there was disappointment over the fact that the population announced by the census was below expectations and it was claimed that there had been serious omissions.

Hill said that the claims didn’t amount to much in the end. Still, they ate up precious time. In Hill’s analysis, slowing population growth led to disappointment and disappointment led to formal complaints. We’ve seen what happened next. The conduct of a census isn’t pretty. If one looks too closely, the flaws stand out. And in 1920 millions of Americans looked closely at the census, in New York and around the country.

The 1920 census was not an exceptionally flawed census. But it showcased its flaws with flair.

This post is published under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license by me.