Standing on the Crater of a Volcano

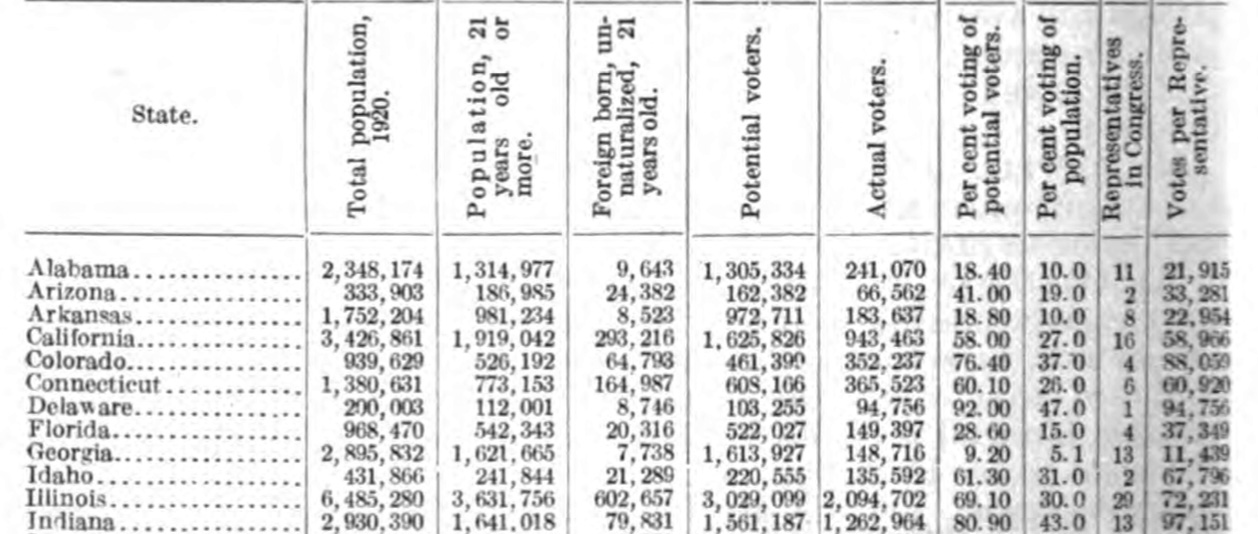

This is a story about anti-racist data, its advocates, and its powerful enemies. It is a story about a table of numbers that Civil Rights activists built from just-released census figures in 1920, which they combined with publicly available voting data, to prove that Southern states had deprived Black Americans of the right to vote. That table of numbers began like this:

We sometimes say that data speak for themselves. That is a metaphor of course. Data can never speak. We mean in such situations that a set of observations have been gathered and organized such that they tell a story or a make a point. A person, or many people, stand behind every data set that’s supposed to speak for itself. There’s always a story behind a dataset that speaks for itself, a story like this one, whose hero was James Weldon Johnson.

In 1900, James Weldon Johnson wrote “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” a poem that became a song that became the “Negro National Anthem.” (Here’s Rochelle Rice performing the song, as curated by the National Museum of African American History and Culture for Juneteenth.) Johnson, with this brother, wrote dozens of other songs for Broadway too. He also wrote an anonymous, but celebrated, novel. None of the members of Congress who grilled Johnson on one of the last days of the year 1920 appear to have known that the man sitting before them was a treasure of American arts and letters, a writer and poet who would help kindle the “Harlem Renaissance”.

When an enumerator named Lillian Chappell counted Johnson, living in Harlem, on the 7th of January, 1920, she put down his occupation as “author,” an apt enough label but hopelessly far from capturing the whole person.

Johnson was not only an author—a novelist, poet, and song-writer. He was also a political organizer, a diplomat, and beginning in 1916, the field secretary of a recently founded organization that fought the indignity of Jim Crow segregation, the bloody rule of lynch law, and the theft of political power from formerly enslaved people and their progeny. That organization was called the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the NAACP.

In the second verse of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” Johnson had testified to the violence, injustice, and heartbreak borne by African Americans since long before the United States declared its independence, writing:

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered;

We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered

Tears watered the way and blood still stained the path when Johnson testified before a Congressional committee on December 29, 1920. If the Congress members did not appreciate who it was they were listening to, the poetry of Johnson speaking prose might have given them a clue. Here’s one of his testimony’s crescendos, as he pressed the Congress to act, and drew out the stakes of inaction:

You are met with a practical, everyday question. We are standing on the crater of a volcano. How long can that situation go on?…It is a fact and the white light of truth beating on it is bound to reveal it. You have got to meet it with wisdom.

Yet wisdom seemed to be in short supply in Congress.

Johnson appeared before the House Committee on the Census to demand constitutional justice. The Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution granted equal citizenship to the formerly enslaved, and beyond that affirmed the citizenship of any and all persons born in the United States. It also repealed the infamous 3/5s clause, which had counted enslaved African Americans as only 3/5s of a person for the purposes of apportioning representatives in Congress or electors in Presidential contests. The second section of the Amendment began with this sentence:

Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed.

If I may be allowed to step out of the past for a moment and into our present: this is an inconvenient sentence for President Trump, who last week issued a memorandum declaring his intention that the apportionment figures transferred to Congress in 2021 should exclude “illegal aliens.” This despite the fact that the “whole number of persons” in the Constitution clearly includes all people who live, work, and build communities in the several states, without regard for their citizenship or immigration status. The administration’s order contravenes nearly a century of established presidential practices, as is made startlingly evident by this site by Taylor Savell and Kevin Ackermann.

Striking out the 3/5s clause credited Southern states fully for their Black inhabitants. States that had very recently been in open armed rebellion were to be granted substantially greater political power. To assure that those states’ Black residents had some say in their governance, section two continued with these lines:

But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice-President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State.

If states disfranchised otherwise eligible men, their representation could be reduced—or that’s what the Constitution now said. But that power had never been used up to the moment that Johnson sat before Congress.

At first, armed occupying forces from the North assured the voting rights of African Americans, and so this amending sentence had little purpose. By the mid-1870s, though, well-armed whites-only Democratic groups formed militias, overthrew or intimidated local Republican officials (who had been duly elected by Black and white voters), and terrorized Blacks in their churches or Republican club meetings, or when they came to the polls to vote. “Across the Deep South in the states where Republicans still had power,” writes historian Justin Behrend, “Democrats took notice of the ‘Mississippi Plan’ and the violence that ‘redeemed’ the state.” When even violence could not intimidate Black voters, the frustration of Blacks’ voting registration and outright vote fraud completed the job of stealing elections. After the 1876 bargain that handed the presidency to Rutherford B. Hayes, even Republican presidential administrations gave up on policing elections.

In the following two decades, when violence had failed to fully suppress Black political action, Southern states completed their coup by establishing whites-only primary elections and new voting restrictions based on literacy and a hefty poll tax. As Behrend writes, “Because of the persistence of black politics and freedpeople’s insistence throughout the 1880s that an open and grassroots democracy be restored, exasperated Democratic leaders turned to disfranchisement as the ultimate means to stifle freedpeople’s collective power.” White supremacy rose in final decade of the nineteenth century by stripping Blacks of the right to vote. Congress did nothing to protect the voting rights of African Americans, nor did it take away representatives from the States that had suppressed those rights.

“We all know very well that the colored people generally throughout the Southern States are not allowed to vote under the same qualifications and under the same requirements as the white citizens,” said James Weldon Johnson. His NAACP colleagues preceding him before the committee sought to remind everyone on the committee of what everyone knew by presenting signed affidavits of individuals denied the right to register or to vote in 1920. Johnson at this point presented data that he hoped would speak for itself.

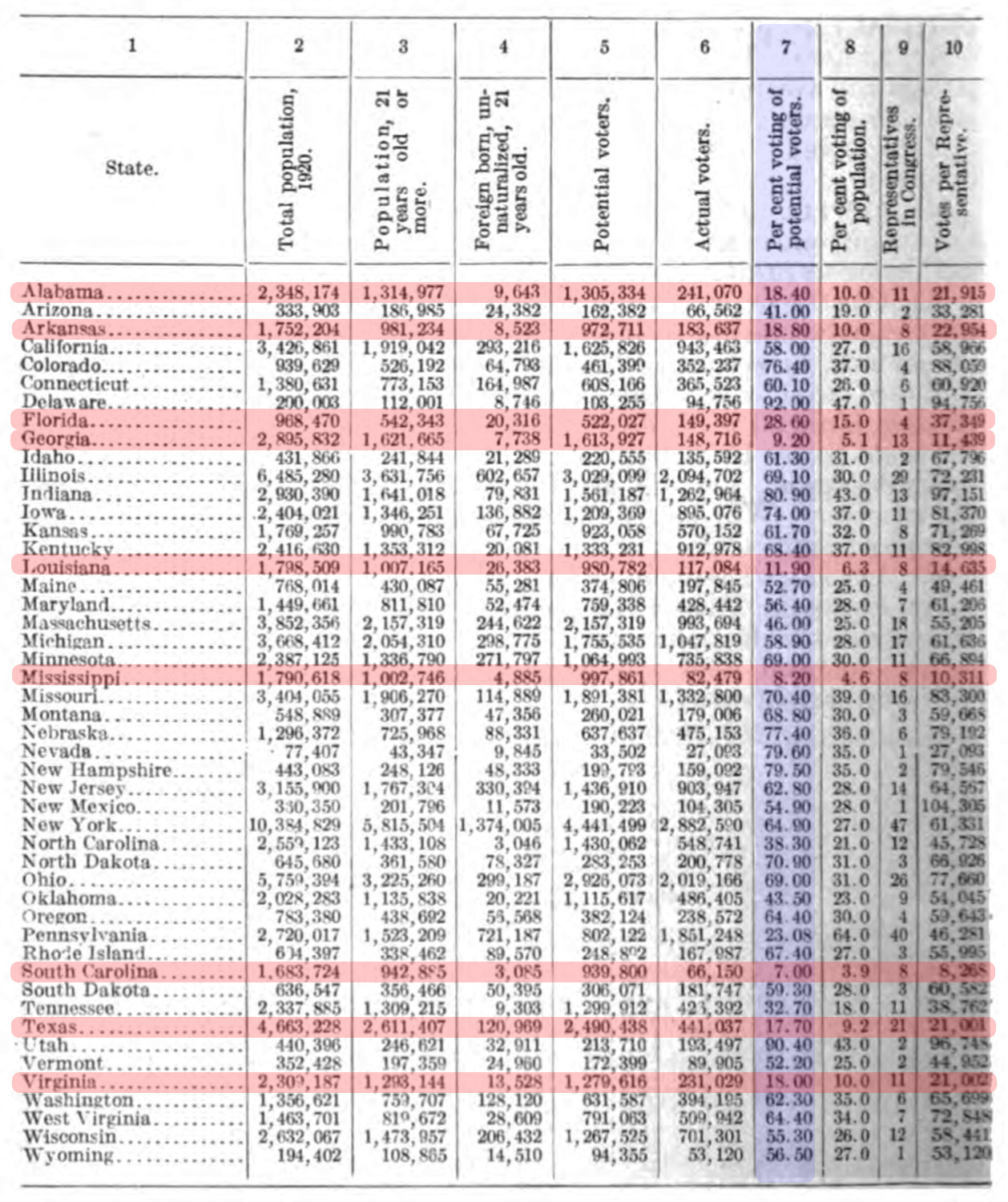

The table listed each state, followed by that state’s preliminary population total from the just-completed 1920 census. The next column listed only those voters old enough to vote (those over 21 years of age). Next the table listed the number of unnaturalized “foreign born” who would be barred from voting in many states. Subtracting the unnaturalized from all 21 years olds yielded column 5: “Potential Voters.” The next column contained the totals for actual voters in the 1920 presidential election. The ratio of potential to actual voters became a percentage in column 7, which I have highlighted in blue. Next come columns showing the percentage of the total population that voted, the number for representatives in each state, and the number of votes cast per representative.

That data—having been expertly organized—does really seem to speak for itself. Still, I’ve used some highlighting to amplify its message.

Most states ended up seeing votes cast by somewhere between 50 and 80% of potential voters. New York, for instance, saw 64.9% of its potential voters actually vote. The highest rate was in Delaware, where the figure was 92%.

Then there were the states at the bottom of the heap, with the lowest percentages of actual voters, all below 30% and quite a few in single digits—I’ve outlined them in red. They were: Florida, Arkansas, Alabama, Virginia, Texas, Louisiana, Georgia, Mississippi, and (bringing up the rear with only 7% of its potential voters voting) South Carolina. The conclusion was hard to avoid: voters didn’t (or couldn’t) vote in the Deep South.

(There’s something funny with the Pennsylvania figures, which seem to show more actual voters than potential voters, but a very low actual/potential voter ratio. I suspect a typo somewhere.)

The table evidenced the disastrous efficacy of the disfranchisement campaigns. That was Johnson’s point, and now he asked Congress in 1920 to use the power granted it by the Constitution to bring about justice. Johnson and his colleagues did not really want to see the South lose representation. They preferred to see the voting rights of all Americans respected. But failing that, the South should certainly lose some House seats. Reading the transcript of the proceedings, Johnson’s statement stopped me short:

“The Constitution provides certain things which were laid down in the fourteenth amendment, and Congress is given the power to put that into execution. If Congress says it does not know how to exercise that power, that is the misfortune of Congress.”

The misfortune of Congress, and all who sought justice….

In response to this table, the actions of Representative James B. Aswell of Louisiana suggest that he too believed that the data could speak for itself. He feared anti-racist data.

Aswell had tried from the start of the hearings to shut down the entire discussion. To the general counsel of the Colored American Council, Aswell asked—thick with patronizing condescension—“You do not understand that this bill [for reapportionment] has not anything whatever to do with the proposition of voting?” Aswell was only correct insofar as Congress had failed to enforce the 14th amendment. Johnson and his colleagues hoped very much to make the apportionment bill have quite a lot to do with voting. Now, as Johnson submitted his data, with the idea that it would be published in the official proceeedings of the committee, Aswell objected.

“This Congress is very strong on economy,” he said. Aswell tried to use cost-consciousness to muzzle Johnson and his data. He continued: “We ought not to print all of this. It is extravagant.” He tried, unsuccessfully, to prevent the data from speaking.

Committee members feared other documentation from the hearing too. The committee’s session was scheduled to be photographed, but its Southern members refused any photograph with Black men testifying in the chamber.

The NAACP came to Congress seeking legislation, but also seeking exposure. They had facts that they wanted to air, facts they needed to be recognized. The hearing, with its published record, promised a wide-reaching and legitimate venue. Johnson’s statistics did not mention race or even gesture at it, but the context made it plain that they were intended to contest anti-Black racism. He intended to make Congress publish anti-racist data. And he succeeded in that goal.

This was important as a counterweight to the other purposes that census data were put to in public conversations around “the color line.” When statistics from the 1920 census concerning African Americans occasionally made their way into the white press earlier in the year, they usually stood as evidence of the extent of the Great Migration. Chicago’s Tribune announced a “jump” of nearly 150% in the city’s Black population. Most stories set rates of growth for the white and Black populations next to one another, honoring the color line even in statistical presentations, under headlines like “More Negroes in Cities.”

But the members of Congress did their best to dull the influence of the Civil Rights leaders’ arguments.

They tried denial and distraction first. When the NAACP brought evidence of state officials deliberately delaying the registration of black voters, or denying them registration because they could not read the Constitution faster than the registrar could, the members replied: well, have you tried suing those officials? This doesn’t seem like our problem they said, over and over. Committee members repeatedly dismissed the NAACP’s 941 affidavits signed by individuals who had been denied the right to vote. Those documents and the rest of the NAACP testimony were simply “hearsay” and so inadmissible (even though this was a Congressional hearing, not a court). Then, incongruously, committee members talked at length about the things they had heard from their constituents. Using the “n”-word frequently, probably to cow the witnesses, committee members claimed that many Blacks in their communities voted, and voted for them. Committee members would name one Black person, say he had voted, and thereby deny the entire case. Their favorite defense could be loosely paraphrased as, ‘some of my most loyal constituents are Black.’

Taking offense proved a powerful tool of white supremacy. Congressman Carlos Bee of Texas said, early on: “I would like to know if the members of this committee have to sit here and hear a commonwealth insulted by the witness. If so, I do not care to remain…” Committee members pretended that the reasoned protest before them was in fact a vicious insult—with an aplomb that would have done honor to an antebellum gentleman bound for a duel. Committee members seized on offhand statements about “lawless” men and endeavored to turn the conversation away from substantive discussions and instead toward a full throated defense of their states. They yelled “slander” and interrupted the witnesses. Representative Frank Clark of Florida, defending the honor of his state from the accusations that Johnson and Walter White had leveled filled the record with pages upon pages of documents signed by Florida’s local officials. Johnson had reported that local Florida officials obstructed the registration and voting of African Americans. Congress allowed Clark to bury Johnson’s accusations in puffed up denials from the very officials charged with breaking the rules in the first place. Representative Aswell’s concerns about economy did not surface now that his side was bringing its evidence.

The white press played along, thereby suppressing the voices of the Black activists. An Associated Press story from 30 December reprinted a remark by Representative Jacob Milligan, asserting that Black women had prevented white women from voting in Missouri. The story also reported “somewhat exciting scenes” in the committee meeting. In the process, the reporter sanitized the speech of Congress. In the Congressional hearing, Representative Milligan had used a clear racial ephithet, the “n”-word, but the Associated Press silently replaced it with the more respectable “Negro.” Only at the very end of the article did the reporter discuss the NAACP findings. And a similar story the next day was even worse, printing nothing about Johnson’s data or any substantial claims about the extent of disfranchisement. Instead the article featured Representative Larsen’s baseless accusation that the NAACP “maintained secret agents throughout the South and thrived on propaganda.”

The Black press, in contrast, gloried in the NAACP’s apparent victory. The Washington Bee called the testimony “one of the most notable occurrences in race history of the past few years.” The NAACP, the paper reported, “put the South on the defensive by supporting a good case with a thorough and complete knowledge of the law applicable to the situation…” The Negro Star noted gleefully that “Congressmen from the South, who are holding their memberships because of disfranchisement of Colored Americans, ‘had their feelings hurt’ and became noticeably peeved.” The article subhead read “Undeniable Facts Laid Before the Committee” and it went on to detail those facts, rather than discuss the outrage of the whites. Speaking after the session to a reporter, James Weldon Johnson deplored the “obstruction” and “attempted intimidation” by members of the committee. “Unfortunately,” he said, “the scandal is not only national, it is international. United States citizens are taunted the world over with the hypocrisy of pretending that they enjoy a republic form of government when, by force, fraud, and violence, colored citizens are deprived fo the ballot and are murdered in cold blood when they claim this prerogative of ther manhood and womanhood.”

Representative George Tinkham of Massachusetts stepped forward as a fierce advocate on the side of Johnson and the NAACP.

Earlier in December he had put forward legislation empowering the Committee on the Census to conduct a sustained investigation of voting practices in any state that might be limiting the franchise. Tinkham’s approach threatened, in the words of the Black-run Savannah Tribune, a “battle for distribution of seats in Congress and the electoral college upon the basis of voters permitted to participate in elections.” (This frame, we’ll see, eventually had unanticipated consequences in the context of debates over immigration.) Tinkham argued that any limitation of the franchise beyond age and citizenship could be counted as an abridgment of the franchise. As his colleagues noted over and over, that meant that Massachusetts’ use of a literacy test for voting would count as a disfranchising act, just as literacy tests and poll taxes in the South did. But as everyone also recognized, literacy tests barred a much smaller portion of the population from voting in Massachusetts than in the South. Tinkham was fine with all this. His proposal aimed to convince all states, including his own, to get rid of their literacy tests.

Tinkham refused to accept that Congress had any other option here. Congress had to address disfranchisement. It had to take representatives away from states that denied the vote to their citizens. He said:

“We are here to make an apportionment of the Representatives which shall be constitutional and legal. It can not be constitutional and legal if there is disfranchisement, and it becomes the duty of the committee to take up the question of whether there is disfranchisement or not and determine on some rational basis of how that disfranchisement is to be measured and fixed, and then apply the rule of reduction.”

An apportionment that did not account for disfranchisement would be unconstitutional, argued Tinkham.

The NAACP had initially said that literacy tests and poll taxes were legal, that they objected only to the unfair administration of those tools in a way that hurt Blacks disproportionately. Now the group picked up Tinkham’s banner too, agreeing that Congress had no choice but to remove representatives from all states with literacy tests.

The data had been made to speak, by James Weldon Johnson and his colleagues, and it spoke in frank accusations of serious injustice. Members of the Census Committee had done their best to silence the NAACP and its data. Now the question became: Would Congress step up and accept the mandate of the 14th amendment, or would it once again shirk that responsibility?

[Find out in the next installment of this series on the 1920 census and apportionment. Just joining in? Here are installments 1, 2, and 3.]

This post is published under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license by me.