Political Solutions to Imperfect Data

This is a story about how politicians in the United States interpreted and judged data in the early twentieth century. It is a story about political solutions to imperfect data.

These solutions were neither neat nor orderly. Democracy seldom is. But they had succeeded in maintaining a data-driven redistribution of power every ten years for over a century.

The whole thing could, and did, get ugly: the chief character in this story, as we’ll see, was a racist demagogue who openly and repeatedly challenged Constitutional norms.

This story begins with a census called into question, it involves a census re-do that never happened, and it culminates in a remarkable abandonment of authority that is seldom remarked upon: in 1929, Congress recused itself from interpreting and judging democracy’s data in its most fundamental use. Congress turned over that power to experts with an algorithm instead.

It all started with John E. Rankin.

Rankin joined the Mississippi delegation in the House as part of the Sixty-Seventh Congress, convening in March 1921. He arrived having just missed the first vote on the question of reapportionment, a vote that divided his state’s legislators. On one side bellowed Paul B. Johnson, who talked of “special trains carrying thousands of Negroes and a great many white people to the northern cities” during the war, a great migration that he was sure was already reversing itself. The census had counted Mississippi’s residents during this abnormal, temporary shift, according to Johnson, and it would be a crime to punish the state by taking away one of it’s 8 representatives as a result. On the opposing side, Hubert D. Stephens and Thomas U. Sisson admitted no injustice in allowing Mississippi’s delegation to shrink. As Stephens put it, “Mississippi, whether she retain the present membership of eight or is reduced to seven, will have the same relative voting strength and influence.” He also denied any power to Johnson’s statistical reasoning: “That census has been taken. That Constitution makes it, and not speculation, the factor that shall guide and control us in the legislation.” Mississippi divided over two, twinned questions: had the census captured an illusory drop in population? And should the House be allowed to expand, saving Mississippi its eight seat?

Rankin picked his side. He entered Congress, took up a seat in the House Committee on the Census, and became a champion for the cause of census doubting and seat saving.

The first thing Rankin ever said in committee was this: “The morning’s paper carries the statement that if men went to the country now in the wheat fields help was so plentiful that they couldn’t get a job.” The people were flooding back into the countryside from the cities. That was his story and he would stick to it for the rest of his days. The 1920 census’s numbers told lies.

He refused to let that census take a House seat away from his state. “Under the census of 1920, as it now stands, Mississippi is to be deprived of a Representative,” he said. “At the time this census was taken, or purports to have been taken, the Great War had just closed and thousands of our young men who were still in the service had not returned to their homes. They were therefore not counted, a great many of them.”

PURPORTS!

What does he mean by “or purports to have been taken”? Whenever I read that line I shake my head—is Rankin seriously casting doubt on whether the census was actually taken in 1920? Rankin’s brazen spinning beggars belief.

Rankin’s story of a flawed census depended too on his faith in white supremacy, on his certainty that Blacks needed the white south. Rankin was sure that the exodus of the state’s Black population would stop, and that Black Mississippians would come back. Rankin told of “a great song that went throughout our section among the Negro population to the effect that they could get better wages elsewhere” during the war, but insisted that “for the last 18 months these negroes have been pouring back into Mississippi and begging the landlords to take them back.” Rankin’s worldview required the state’s Blacks to need Mississippi, to want to come back. There was in fact no stopping the Great Migration, but Rankin had to deny it was happening.

(Rankin’s racism prevented him from seeing clearly what others, like the artist Jacob Lawrence in this painting would one day celebrate: the dignity of the Black Americans boarding trains, fleeing oppression, seeking something better.)

Next, Rankin blamed the weather. It had been “very wet,” he said. And “in some instances [census officials] appointed some old rundown politicians to supervise the work” which produced an “inefficient census.” That census figured Mississippi to have 1.79 million people, a 7,000 person decrease from the previous decade. But Rankin asserted the correct number should be 1.9 million. A few moments later, warming to his topic, swelling with assurance of his own arguments, dreaming his racist dreams of the state’s cotton fields worked again by masses of returned African American tenants, Rankin revised his estimate upwards: there were 2 million in Mississippi—more than 200,000 had gone uncounted. Rankin asserted a terribly flawed count, which coupled with the Republican leadership’s refusal to enlarge the membership, meant that “a great part of the agricultural population of my State will be deprived of representation on the floor of this House.”

For a long time, I mostly noticed Rankin’s disparagement of the data, his critique of the census. But the more I read his speeches and the speeches of his peers among the data doubters, I noticed a pattern. Rankin’s judgment of the census’s flaws did not lead inexorably to a failed apportionment. He and his allies believed the data could still be used—but only if Congress were allowed to increase the size of the House to preserve each state’s delegation.

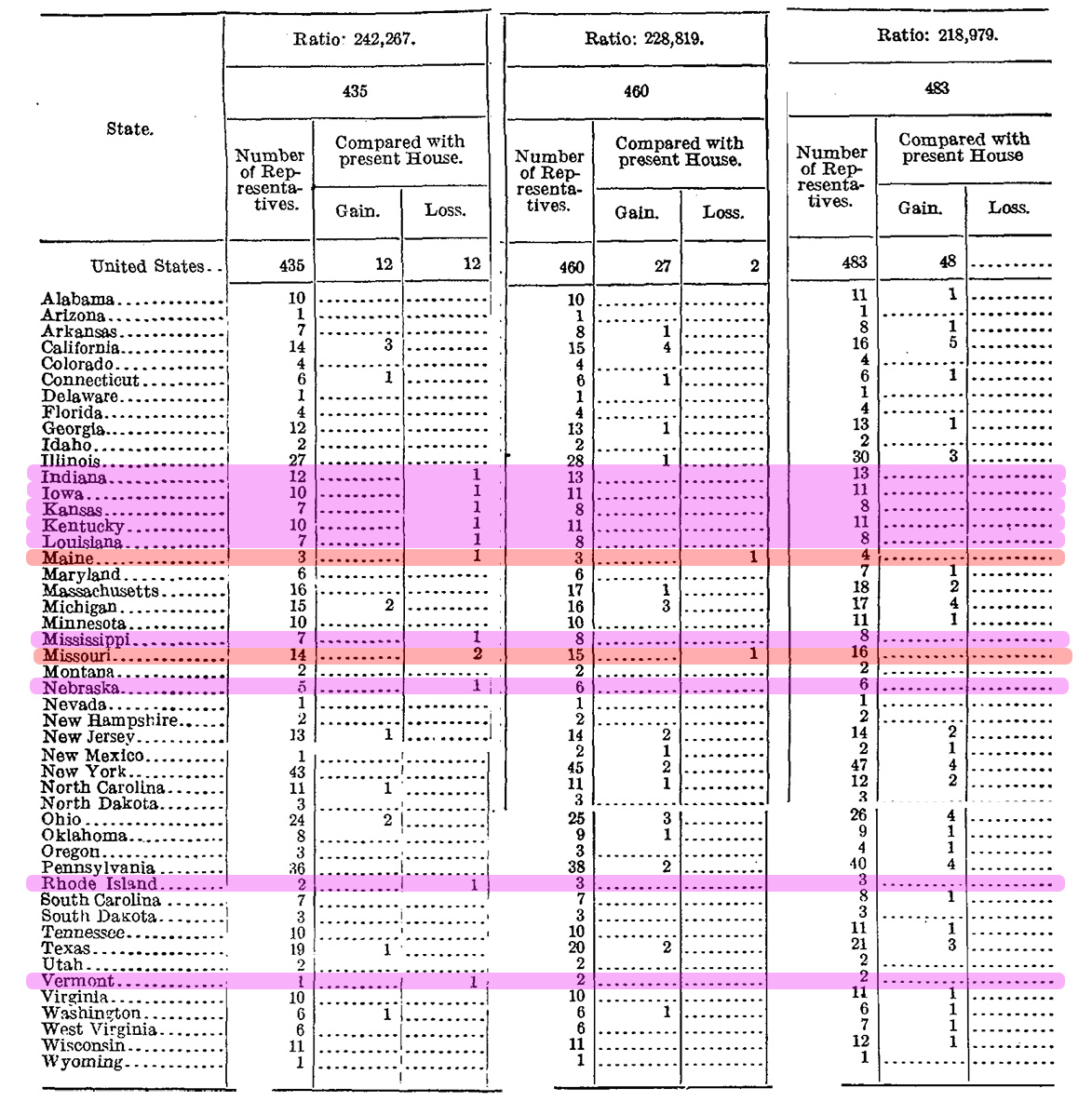

Despite all his data doubting, Rankin stood on the side in favor of a reapportionment at 460 seats when that bill came forward in October 1921. That bill would preserve Mississippi’s final seat. Only Maine and Missouri stood to lose a representative each.

On the House floor, Rankin made his most basic argument: “If we depend upon that census, and reapportion on a basis of our present membership, the agricultural sections will, as a rule, lose their quota of representation.” Two factors combined to malapportion the Mississippi Valley and disenfranchise its farmers: “that census” and “our present membership.” If either were removed, an apportionment was possible.

But the Republican leadership stood firm: the House should stay at 435 members. In a tight vote taken near midnight on a Friday, October 14, the House voted to “recommit.” That vote sent the bill back to the Census Committee where it would linger, languish, and assuredly die. There would be no apportionment in 1921.

It has taken me a while to wrestle seriously with Rankin’s arguments. He’s an unsavory character. In the debate over reapportionment in October 1921, Rankin surpassed all his colleagues in the overt expression of racism and white supremacy, tarnishing the debate with rumors of white women raped by “brutal” Black men, warning that white women would vote out of office any who stood up for “Negro equality.”

He’s also clearly self-interested in his arguments. As the most junior member of the Mississippi delegation, I suppose—and I imagine he supposed—that his district and his seat were among the most likely to disappear if the state lost a representative. No wonder he fought for Mississippi’s seat with such ferocity.

Beyond his racism and selfishness, Rankin’s argument also always struck me as faintly ludicrous. The size of the House, I reasoned, would not really have any effect on the “quota” of each state’s representation. A smaller House penalized each state equally, in proportion to their population. That was the point of using mathematical methods that tied representation to population. It should be equally fair for all states, whether there are to be 300 or 400 or 500 or 600 seats. Indeed, I saw this argument made even by some Mississippians.

Yet there’s no getting around the fact that Rankin and many of his colleagues judged losing a seat to be a truly terrible outcome for for a state and its politicians. The more I thought about it, the more I saw their point. Losing a seat forced a general redistricting that could imperil many sitting incumbents (at a moment when no federal laws compelled the regular redrawing of Congressional lines). More importantly, losing a seat assured at least one incumbent wouldn’t be invited back to the Capitol. That could be a great loss, if the incumbent who was left at home had been a power broker in D.C. Over time, representatives gained seniority in their parties and ascended to positions as chairs of important committees responsible for directing funds home, seeing to the needs of constituents, or deciding which bills would be given a chance to become laws. Decreasing the size of a state’s delegation might result in that state losing not just any representative, but one who wielded disproportionate influence in the House.

It slowly dawned on me that there was a logic to the argument—Rankin’s argument—for fixing a flawed census by increasing the size of the House.

That logic went like this:

The data deserved to be doubted.

->

The census was too uncertain to use it to take away a state’s representative, which was a very great punishment.

->

But it was not so uncertain that the U.S. could not reapportion at all.

Increasing the size of the house served as a mechanism for dealing with imperfect data.

But the Republican leadership had decided the House should be frozen at 435 seats. So how could Congress deal with the data’s imperfections?

The new director of the Census, William Steuart proposed a new census, a re-do.

Steuart’s 1921 report to the Secretary of Commerce repeated, and did not refute, accusations against the census made on the House floor. It asserted a “shifting of the population just prior to and following the census.” It noted “considerable dissatisfaction with the result of the count” and reported that it had “frequently been contended” that the census results reflected an “abnormal” distribution of the population. (Steuart neglected to mention that the abnormality of the census had been asserted in Congress before it was even taken.) Steuart’s report repeated the claim that “there was a great movement from rural to urban districts” before the census and the much more questionable claim that those migrations had been “neutralized in large measure by a reverse movement” after the census count. The Census Bureau lent legitimacy to Rankin and his data-doubting peers.

Steuart’s report concluded that if the data were confirmed to be flawed—or potentially flawed—then it made sense to count again. “The Census Committee of the House is now considering the introduction of a bill providing for another enumeration of the population in 1925 or some other year prior to the next decennial census,” wrote Steuart. “This proposed legislation has my approval.”

But what did the Secretary of Commerce think?

That is what the Census Bureau surely wondered. But it was also a question addressed directly to Hoover by ordinary Americans who were following the census.

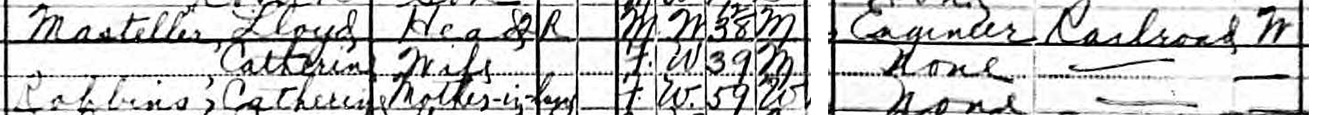

For example, Mrs. L. W. Masteller, from Jersey City, wrote Hoover to ask about retaking the census. Mrs. Masteller didn’t have to worry about not showing up in the census herself. An enumerator named Elizabeth O. Crown made an entry for Catherine Masteller on 5 January 1920. She recorded Masteller as a native-born American, the child of Irish immigrants, who now lived with her husband Lloyd, a railroad engineer. Catherine’s mother, who was a naturalized citizen, also lived with them and was counted.

Hoover’s secretary replied to Catherine Masteller with this excuse: “The chief difficulty in connection with taking another census before the date fixed by law is that no appropriations are available for this purpose.”

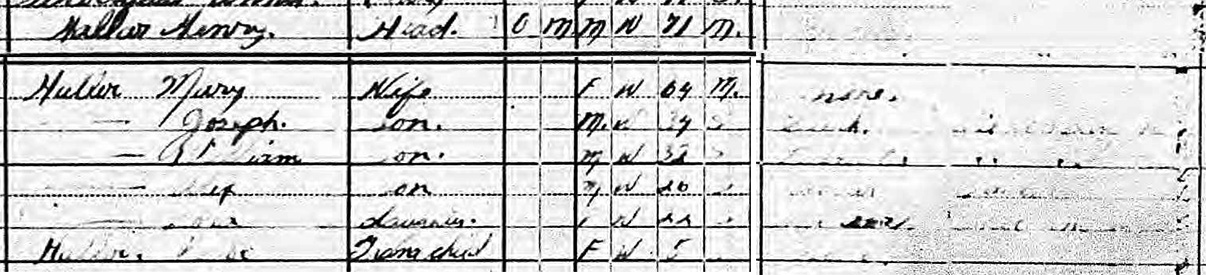

Joseph E. Hallar of Wausau, Wisconsin also wrote Hoover about the census. A census enumerator counted Hallar in 1920 living in a house with three generations of his family. Joseph was 34 years old and a clerk, although the records aren’t clear enough for me to make out what kind of clerking he did. Both of his parents lived in the house, as did his sister and two brothers, and a grandchild whose parent could have been Joseph or any of this siblings.

Hoover’s secretary told Hallar the same thing: no funding, no new census.

Hoover’s fellow Republican, George Tinkham of Massachusetts—the same George Tinkham muzzled by Congress for his fight to punish the South for stealing the ballot from African Americans, the same one who Rankin accused of an “iniquitous scheme” to rob Mississippi of representation in the name of Civil Rights—also wondered what Hoover thought. Tinkham set aside the question of Congressional appropriations. Say that Congress approved the money, he asked, did Hoover think a new census was a good idea?

Few Secretaries of Commerce took that office or have taken it since with the statistical credibility that Herbert Hoover had. Hoover graduated from little-known engineer to national celebrity during World War I when he organized the campaign to feed Belgium and then stepped in to serve President Wilson as the U.S. Food Administrator. President Harding tapped Hoover for Commerce, where Hoover set about building up an even more robust statistical operation centered around monitoring industry closely, defining economic trends, and predicting economic futures. If anyone could be convinced that more statistics would lead to better governance, it was Hoover.

Hoover admitted that the Census Bureau—or Steuart—seemed “greatly impressed with the shifting population.” But Hoover couldn’t get beyond the cost of a new count: “in the present economic state of the country we are not warranted in the expenditure of the very large sum of money which is required to conduct this investigation.”

There wouldn’t be a recount.^

Henry Ellsworth Barbour, a representative from California, decided to force the issue of apportionment once again in 1924. He sat on a Census Committee that refused to recommend any new apportionment bill. He wanted to put that refusal, which was a refusal of Congress’ Constitutional responsibilities, on the record before the full House of Representatives.

Barbour recited the liturgy of abnormality: “It has been contended that the last census was taken under abnormal conditions,” he began. He mentioned “an unusual movement of population from the country districts to the cities” and its reversal. But there he stopped to contest this congealing conventional wisdom.

Hadn’t the movement of population from city to country “been going on for a considerable period of time”? That was the Census Bureau’s published position.

Barbour stood up for the census, as both correct and legitimate. “The last census fairly represents conditions at the time it was taken,” he said. Barbour remained willing to admit “an abnormal movement of population” but would not let that movement serve as an “excuse for the failure by Congress to do its duty under the Constitution.” The census captured America as it was at that moment, and that was “the only basis upon which Congress can act.”

But Congress would not act if John Rankin had anything to do with it. Speaking to Rankin and of Rankin, Barbour explained “My friend from Mississippi knows as well as I do that for the past three years I, for one, have been working to force the bill out of the committee and the gentleman from Mississippi has stood at the bridgehead and blocked the way.”

Rankin won again in 1924. Barbour would keep trying for years to come.

Throughout the 1920s, John Rankin put on a very convincing show of really believing the census had been exceptionally flawed. I think it’s possible—even likely—that he really believed in its badness.

“Under ordinary conditions,” he said in 1926, “I would have been in favor of reapportioning in 1921.”^^

He listed the reasons the 1920 data would not allow for a sound reapportionment. There was the problem of the abnormality caused by war, front and center—many men were still in the military or had been lured away by still-humming wartime industries. Rankin could also draw on a host of other procedural problems to justify his and his state’s stubborn seizure of power. Rankin knew about those problems because the Census Bureau and its allies had reported them. Back in 1920 as the count had been winding up, the then-director Rogers blamed bad weather and bouts of lingering flu for some serious delays in the count. But people within the Bureau refused to scapegoat the weather (and the decision to start counting in January), when the biggest problem was personnel. It had been nearly impossible to attract and retain good people at the offered wages.

Rankin could read about census problems in a 1923 report by representatives of the American Economic Association and American Statistical Association, one that praised the 1920 census and called it a remarkable achievement, especially because of the challenges it had overcome. The report said that in “no preceding census have there been encountered so many serious obstacles.” And it detailed those obstacles: “This was the first census ever taken in midwinter, and the weather, especially in the Northern States, was unusually severe, so that the work of enumeration, particularly in the rural districts, was greatly hampered. Another handicap resulted from the fact that the census was taken at a time when, because of the prevailing high salaries, wages, and prices, it was extremely difficult to secure competent persons to accept employment as enumerators at relatively low rates of pay which the Bureau of the Census was able to offer.”

In 1926, Barbour tried to put all these problems in context. He tried to show them to be what they were: ordinary errors, the problems that stemmed from trying to count an entire continent-spanning nation. He called up Joseph Hill, the Census Bureau’s most senior statistician and asked for help. Hill acknowledged the problem of bad weather, but contended that weather only caused unimportant delays—it didn’t foul up the numbers. He acknowledged “some degree” of war-caused abnormality, but also noted that “the population of the “United States is always shifting more or less.” Every census faces such troubles. Some people get missed, others are counted twice. “In every census there is a slight margin of error.” But when it came to the 1920 census, Hill’s expert opinion, shared by most of his Census Bureau colleagues, was that “we have no reason to believe that errors of this kind were any more frequent at the census of 1920 than at any other census, or were serious enough to vitiate in any appreciable degree the substantial accuracy of the results.” Barbour presented these reassuring conclusions at a 1926 Census Committee hearing.

Rankin attended that committee meeting. He heard Hill’s case for the data. But he chose to remember only the reasons for doubting the data, probably because that choice suited his cause. Speaking after Barbour presented Hill’s assurance, Rankin blithely insisted that census supervisors “found it impossible to get men to go out in the country and take the census” in 1920. As a result, they missed people. Lots of people. Rankin felt certain that he himself had been missed. “I told Mr. Steuart that I would dare say he would not find my name on the census roll, and the same is true of hundreds of other people,” said Rankin.

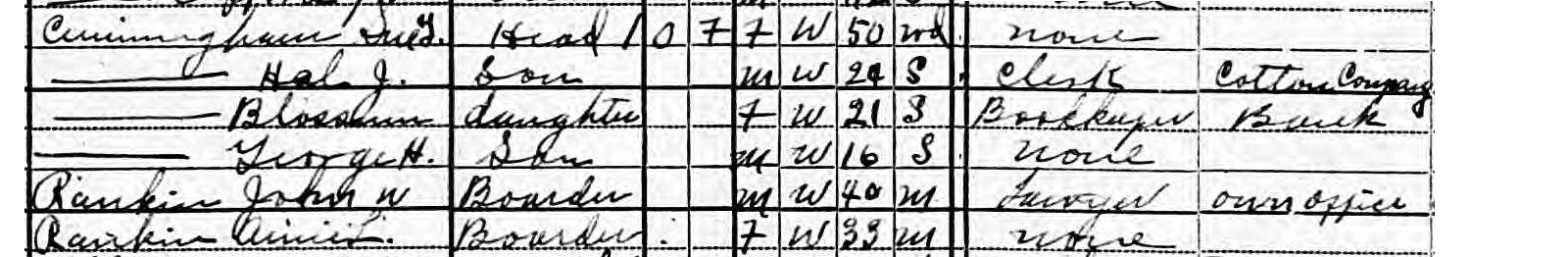

Dear Reader:

(That’s Rankin and his wife Annie, who were apparently renting a room from a widow named Sue Cunningham. Rankin had not yet been elected to Congress and so is listed as a laywer.)

Rankin displayed similar bravado in other venues, including in situations where he didn’t need to posture. Writing to a constituent in 1929, Rankin pooh-poohed the predictions of those who thought Mississippi in 1930 would lose two seats. One seat? Maybe, he said. But more likely none. He explained his reasoning:

The Census of 1920 was taken when we were just emerging from the World War, and when many of our people were out of the state. It was also taken in the winter time when the weather was very bad, and those in charge of the work found it impossible to get a correct census of our country people. It was taken at the peak of high prices, and they found it absolutely impossible to get men to go out into the country and take the census for the small allowance provided at that time. As a result, the census of 1920 as finally reported, showed a decline in population in Mississippi. A correct census of 1930 will show that we have increased in population, and in my humble judgement, we will hold the number of Congressmen that we now have.

Rankin really believed it deserved to keep all it members. And he really believed a bad enumeration would have robbed the state in 1920.

So ahead of the 1930 census, after legislation had passed that made apportionment automatic, Rankin poured his energy into getting a good count in Mississippi. He wrote letters to (politically appointed) census supervisors across the state exhorting them to choose their enumerators well. “In 1920,” he told them, “we failed to get a full, accurate, and complete census of the people of Mississippi—especially of the country people—and as a result we were scheduled to lose one member of Congress…and would have militated against her greately in the distribution of the various Federal aid funds in which the she now participates.” Rankin took credit for preventing such losses all decade long: “I led the fight which defeated all attempts to reapportion under the Census of 1920.” But now, with a reapportionment guaranteed to happen, it was up to the census to preserve Mississippi’s power. He exhorted powerful men around the state: “I am writing to urge that you impress upon your enumerators the vital necessity of making this Census full and complete.”

The 1930 census eventually showed that Mississippi attained the 2 million residents that Rankin claimed it had in 1920. The state lost one seat.

Rankin fought to maintain in Congress’s hands the power to judge and interpret the census results. This was a very important point for him.

In January of 1928, the House Census Committee reviewed the Census Bureau’s proposal for new legislation to govern the upcoming fifteenth decennial census, the 1930 census. Rankin had become a senior committee member, one of the most powerful Democrats in the room. He liked to talk and the Census Bureau officials in the room had to be nice to him if they wanted to see their proposals become law.

Rankin asked the statistician Joseph Hill if he thought “it would be wise to insert a provision there that this report of the census shall be referred to Congress for its information and its approval and its use?”

Hill didn’t object. His colleague, the head of the population count, asserted the Census Bureau’s right to publish its findings without Congressional approval. Rankin assented: “I understand that you would publish the figures before Congress approved them; but they would not be declared as official until Congress had the opportunity to approve them?” Now Hill did object, a little: “We certify them,” he explained, not Congress.

As the hearing continued, Hill grew more agitated. It slowly dawned on him that Rankin wanted more than a rubber stamp. “It is a new feature,” Hill said, and clearly not a welcome one, “if it is proposed that before those figures can be accepted they must receive the approval of Congress, a political body.” Now that he really understood what Rankin wanted, Hill objected: “as a statistician, I believe I should feel some reluctance in approving that procedure.” (Note the cautious, even timorous, phrasing showing the fealty required for the situation.) He asked the pressing question: “Where would we be if Congress should say, ‘We do not accept those figures’?” Who would settle such a battle between the scientists and the politicians?

Ever since the Census Bureau had become a permanent office, one staffed by independent professionals like Hill, this question had loomed, this fight had been brewing. Census officials believed that they could remove politics from population counting the way one removes a tumor from healthy tissue. Politics was a cancer in the biopolitical imagination of professional statisticians. Even some politicians agreed on this point.

E. Hart Fenn, a Connecticut representative and the chair of the Census Committee, rejected Rankin’s proposal. Why, he asked, should we expect the Congress to be able to approve the census data if it couldn’t approve the last apportionment. “What guarantee have you that it would not be made a political question…,” asked Fenn of the requirement to approve the census results. “I think you would be throwing a political question into Congress which would go far beyond the political questions in regard to the last reapportionment bill.”

New York’s Meyer Jacobstein insisted that Rankin’s amendment was unnecessary because Congress already possessed the power that Rankin sought. Just look at the 1920 apportionment, he said. There the Congress’s refusal to pass an apportionment resulted from its judgment of the census and its judgment of the census’s inadequacies. “The census was not taken properly in 1920, and so we did not reapportion,” said Jacobstein. Gone were all considerations of the size of the house, or the political machinations that foiled the apportionment. Jacobstein simplified the situation and made a vote against reapportionment into a vote against approving the census.

This was a political maneuver. Jacobstein, like Fenn, advocated for an automatic apportionment. His goal was—in fact—to remove from Congress its authority to forego an apportionment. That goal would be foiled by Rankin’s amendment, by the requirement that Congress approve the census results before they could be deemed official. So Jacobstein sacrificed the reputation of the 1920 census—he threw that census under the bus—to advance the cause of removing the census and the reapportionment from direct political control. He was fighting on the Census Bureau’s side.

When the automatic apportionment became law in 1929, the main justification was that it would prevent Congress from ever failing to apportion itself again. But it had two other consequences that were likely even more important. First, it made possible the perpetual limitation of the size of the House. That law and its automatic mechanisms are the reason that the U.S. House still has only 435 seats, even as the American population had tripled in size. Second, the automatic apportionment weakened Congress’s capacity to judge and interpret census results. In 1921, the Congress very nearly passed an apportionment at 460 seats which would have affirmed the census results as good enough, good enough to reapportion just so long as most states and representatives didn’t lose power because of it. Congress’s control over the size of the House and its power to legislate each apportionment were means by which it expressed its judgments about the accuracy of the census and its fitness for use in distributing power within American democracy.

I say that Congress’s capacity to judge was weakened even though I am tempted to write removed, because Congress could at any moment take back its capacity and authority. Congress retains the Constitutional power to write new apportionment legislation. It could—at any moment—override the automatic apportionment law. In doing so, it would also be reasserting its right to interpret democracy’s data—for better or for worse.

^There would be no national recount. Some states conducted their own middecennial censuses. The Census Bureau argued for helping New York State tabulate its 1925 census. Director Steuart proposed to Secretary Hoover, “I would recommend that we offer to run the cards for the New York census through our tabulating machines and to supply pantograph punches for punching the cards at Albany on condition that the State of New York pay all salaries and other expenses incidental to this work, but without making any charge for the use of our machines.” What would the Census Bureau get for this work? It would get more reliable “up-to-date population figures as a basis for showing death rates by age, sex, and color and will be of further use in connection with other annual reports or statistical studies.” Steuart, “Memorandum for the Secretary,” 25 February 1926 31-hhcom-b126-f2210 “Commerce Department Census, Bureau of 1926 January-April” Hoover Presidential Library.

^^Not, Rankin would quickly add, that it was required of Congress to apportion every ten years. He was one of the few voices in the Congress who seldom bothered even to feel bad about Congress’s failure to reapportion. He denied that apportion was “mandatory”, denied more than a hundred years of tradition and Constitutional interpretation, and asserted that Congress got to choose if it reapportioned or not.

This post is published under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license by me.