Close Readings, Big Data...

-

No One Loses at 454 Seats

Today the U.S. Census Bureau announced the official population totals for each state to be used in apportioning seats in the House of Representatives. Here is the data the bureau released.

-

Political Solutions to Imperfect Data

This is a story about how politicians in the United States interpreted and judged data in the early twentieth century. It is a story about political solutions to imperfect data.

-

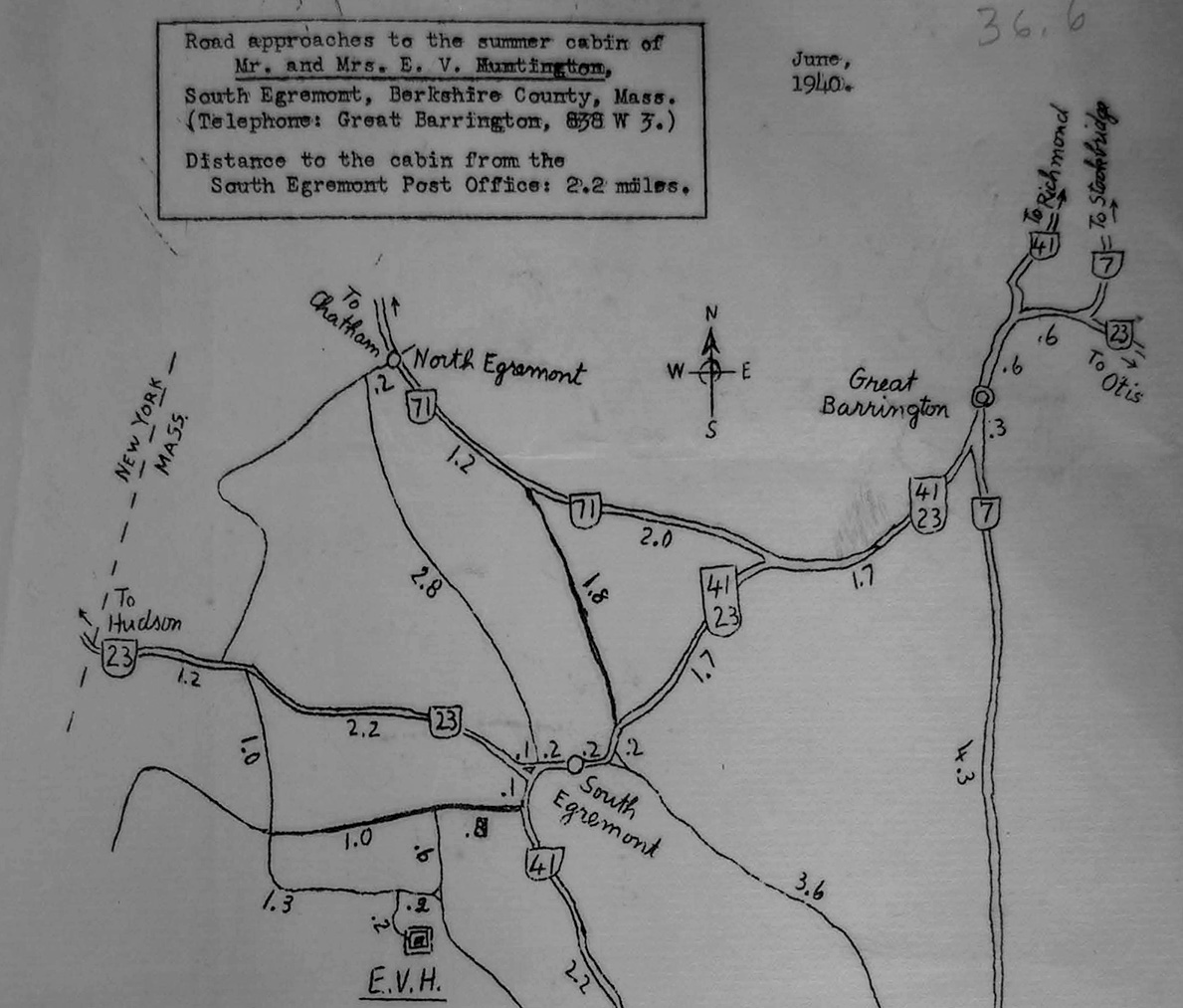

The Harvard Mimeograph

I began writing this essay before setting out on a camping trip. Sitting in the passenger seat of my partner’s truck, our child and two small dogs crammed between us, I thought of a summer vacation I’d just been been tracking through the archives. In 1940, a Census Bureau official drove out to the Berkshires in Massachusetts to find the summer home of a Harvard professor. They had matters of strategy to discuss, as they sought victory in an abstruse methodological controversy that had already endured two decades, and had already helped justify a gross failure of American democracy.

-

A Well-Known Fact

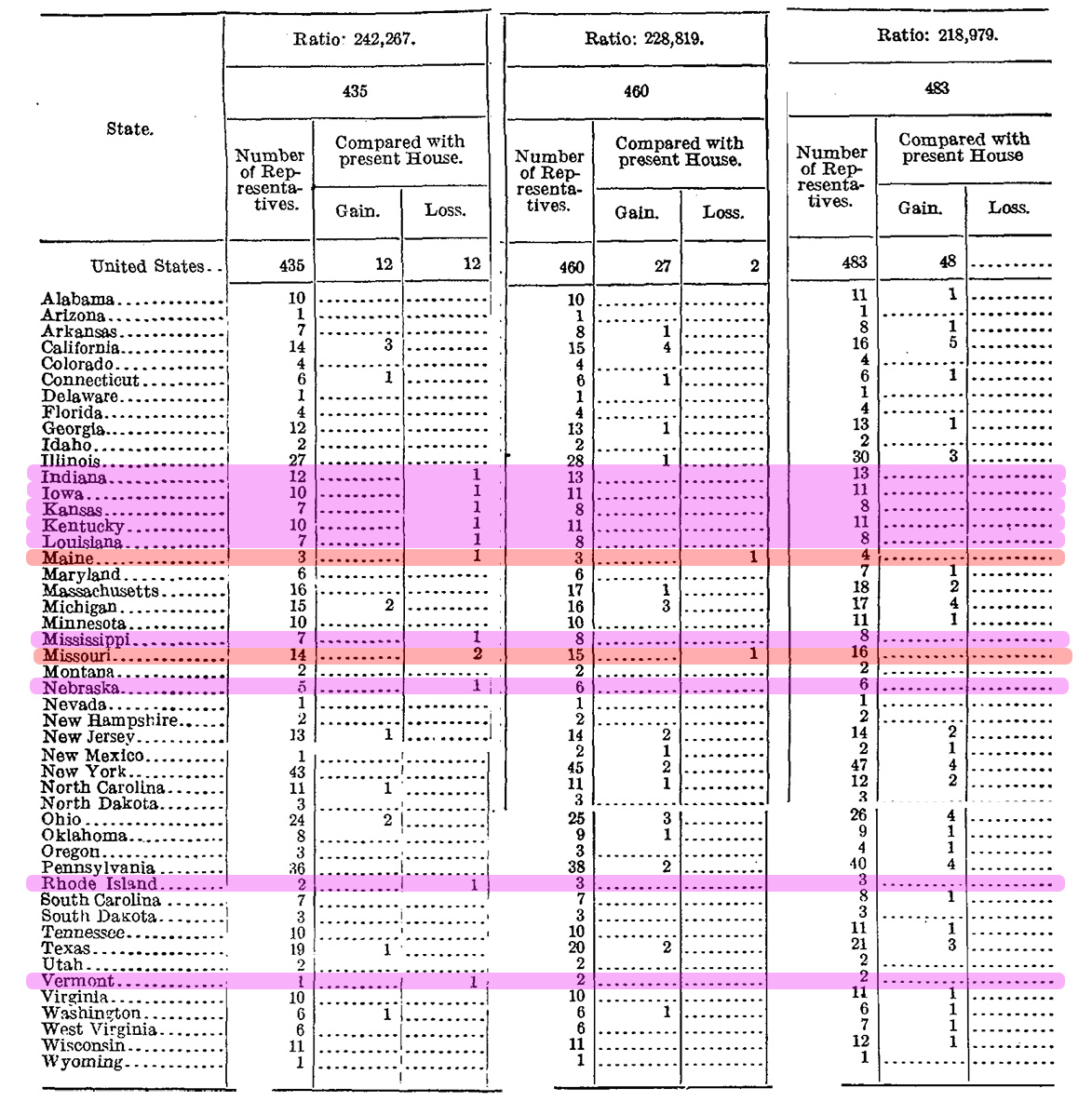

Today we take for granted that the U.S. House of Representatives has 435 seats. Which state gets which seats changes as some state grow faster than others, but the total number stays the same. But that was not the case a hundred years ago. That is why, in December 1920, the Census Committee of the House of Representatives called Joseph Hill, the Census Bureau statistician, to testify. He brought with him a set of 49 tables of numbers, based on the final 1920 population counts for each state, showing the appropriate distribution of seats among the states in a variety of possible Houses.

-

Standing on the Crater of a Volcano

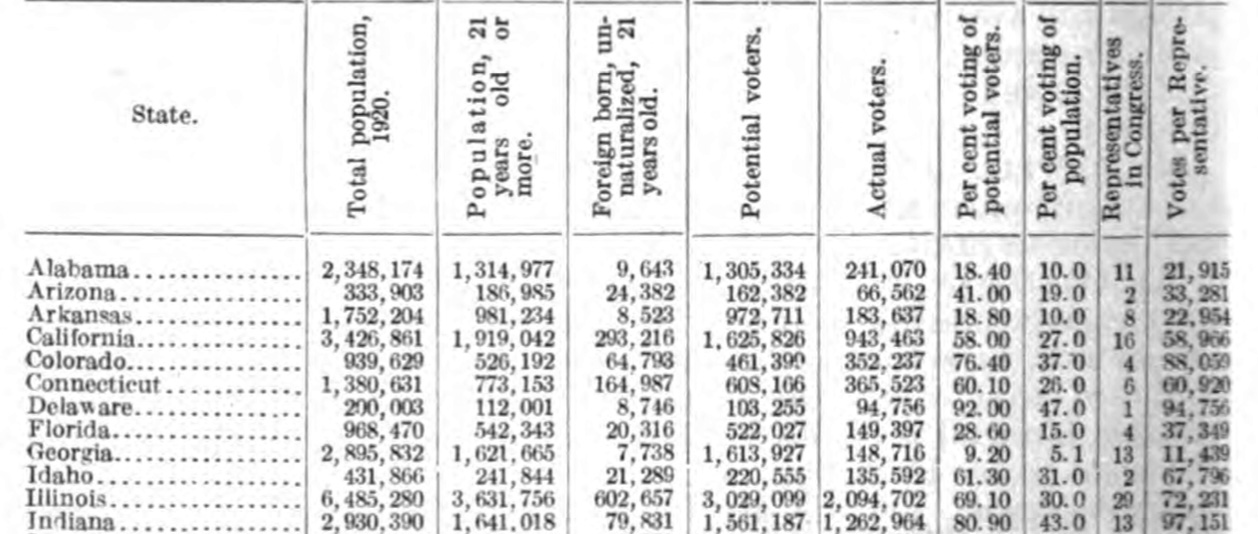

This is a story about anti-racist data, its advocates, and its powerful enemies. It is a story about a table of numbers that Civil Rights activists built from just-released census figures in 1920, which they combined with publicly available voting data, to prove that Southern states had deprived Black Americans of the right to vote. That table of numbers began like this:

-

The (Statistical) Battle of New York

The 1920 census produced reasonably good data. It was, at the very least, not exceptionally bad. This is a crucial point and one we must accept from the start.

-

Abnormal Conditions

The scientists in the census office wanted to purify the nation’s statistical infrastructure. The 1920 census provided them another opportunity to advance that cause. Having won a permanent office furnished by a core of experts and professionals, they turned their attention to rooting out fraud—and politics too. The fixation on fraud, and abnormalities that fraud might introduce into the record, blinded them to a graver danger threatening their census, their authority, and their data.

-

Scientists in the Census Office

Joseph A. Hill was no slouch. Born in 1860, Hill had earned bachelors and masters degrees from Harvard before crossing the Atlantic for Halle in Germany, where he earned his Ph.D. in 1893. Upon his return to the United States, Hill began lecturing, first at the University of Pennsylvania, and then at his alma mater. It must have been Harvard’s president at the time—Charles Eliot—who nominated Hill to join a group of the nation’s most promising young social scientists selected to serve in the 1900 U.S. census.

-

Waving the Dimpled Fist

Dear Reader, if you know a person born just shy of eighty years ago by the name of Judith Blane Gordon, please let her know the census found her back in 1940. Her father said she wouldn’t be counted, because she was a newborn. But she was.

-

The Hand Count

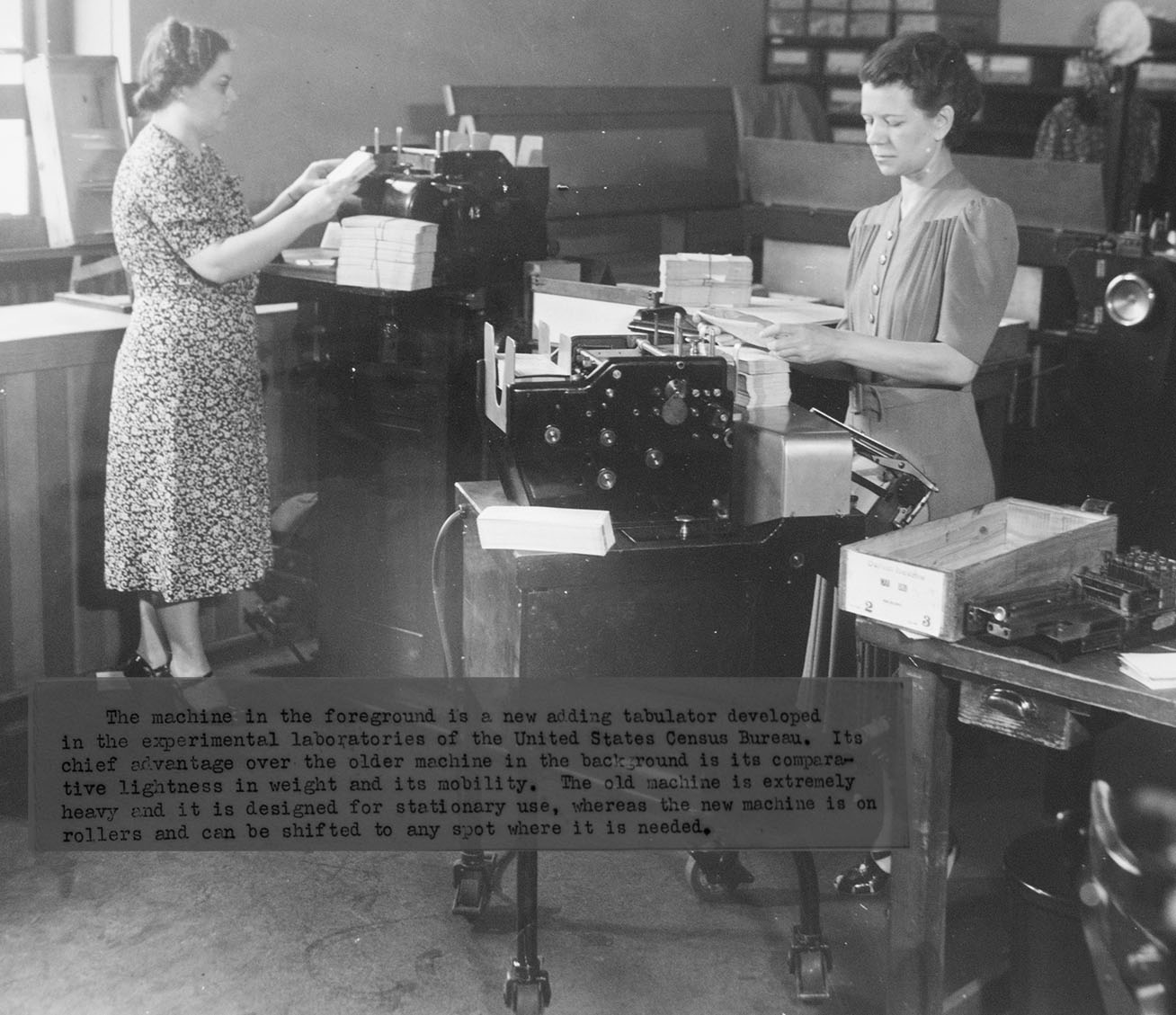

This is what I thought counting the U.S. population looked like in 1940.

-

Print Capital

Quite a few people who I have spoken with over the last few weeks expressed an unexpected kind of surprise when it came to the outcome of the census citizenship question. Plenty of shocking things transpired: to begin with, there was the fact that the Supreme Court shrugged off the administration’s explanation for adding the question, calling it “more of a distraction”(28) than a proper reason. The Departments of Commerce and Justice appeared to acquiesce to that decision, until a presidential tweet (quoted here) reversed everyone’s course for a few days. Now it seems settled: People won’t be asked about their citizenship on the 2020 census. But another thing that shocked (or befuddled) some people I’ve spoken with was that a printing schedule seemed to have decided the fate of the census. Because questionnaires needed to be printed, there was no time to argue anymore about the citizenship question—a point the administration employed to begin with, back when it hoped to convince the court to quickly get rid of all the lawsuits against it at once. Later, after defeat in the courts, the administration had to accept the weight of its own argument. The forms had to be printed. No one pays any attention to a printing deadline, until it defeats some of the world’s most powerful officials. Maybe the ordinary magic of infrastructure and logistics deserves more of our attention the rest of the time too.

-

Refusals and Redlines

Herbert Mace did not want to be seen. He also really wanted everyone to see him not being seen. I began this essay anticipating a story of local resistance and grand politics, another small piece of the roiling controversy that surrounded the census questions of 1940. But as so often happens in these Census Stories, the more I dug into Mace’s story, the more other characters captured my attention and stimulated my imagination. Their adventures seemed superficially more mundane, but on reflection grew in significance. The really exciting stuff can sit right next to the controversy. That’s the case with Mary Brown Bryant, who was a housewife, a sometimes single parent, an agent of American commercial empire, an “unladylike” census taker, and a participant in contentious efforts to inventory Americans’ houses.

-

8 Miles through Alaska, as Mrs. Parrott Rows; Or, Into the Archives!

[Updated and corrected!] On 19 January 1940 in a brief but tantalizing letter, a census enumerator named Mrs. Agnes Parrott outlined a most unusual adventure in enumerating. I smelled a story.

-

Elbertie Foudray and the Adventure of Life

Historians believe in contingency—we insist that the past did not have to turn out the way that it did, that chance occurrences and human choices send the world spinning along one path and not another. So too, contingency governs our research about the past. I never set out to write a book about the dream in 1940 of devising the most scientific census ever. Instead, I went looking for an obscure census mathematician named Elbertie Foudray and, to my surprise, discovered the census. This is a census story all about chance and gender (as well as power) and it began with an effort to recreate a very odd paper machine.

-

Controversial Questions

The 2020 census tumbled into the news again last week. A new question about citizenship had joined the list that all Americans would have to answer, but e-mails made public in the course of a lawsuit cast doubt on how the question got there. Critics of the question cried foul, and I joined them. But as this new census controversy intruded on my Twitter feed, I could not help but also see its similarities to the income question spectacle of 1940. Weren’t we witnessing the drama of another controversial question? Then I stumbled upon a document in the Commerce Department papers (housed in the FDR Presidential Library) that reminded me of a different controversy: a still-too-little-known fight (despite the heroic historical sleuthing of Margo Anderson and William Seltzer) to preserve the sanctity of individuals’ census responses from prying eyes at the FBI. I wanted to know which of these historical census scuffles would allow us to best see our present quandary through fresh eyes? Was this another contested question or another case of law-enforcement encroachment? As I dug deeper, I decided it was neither …

-

Super Snoopers in Montevideo

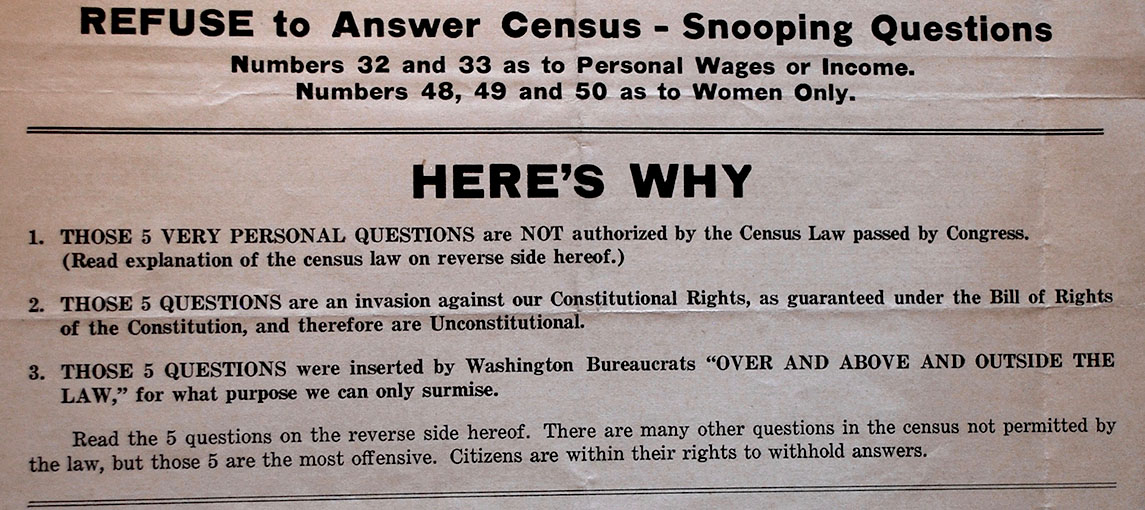

“You’ve Got To Get Mad” screamed a handbill in block-bold letters. The placard traveled along the same blocks where census enumerators roamed in early April 1940. “Stand firm on your Constitutional Rights” it warned. The Constitutional Rights Republican League of Minnesota jeered “Washington Bureaucrats” and their “snooping.” They called on individuals to refuse to cooperate. Few appear to have taken the call to heart. This was a point that census officials celebrated. But as I came to realize while investigating the census returns for small-town Minnesota, the so-called Washington Bureaucrats achieved this success after they preemptively limited their own “snooping.” Many Minnesotans (and their fellow ordinary Americans) may have seen no need to refuse because they could comply with census takers and still keep their household finances secret.

“You’ve Got To Get Mad” screamed a handbill in block-bold letters. The placard traveled along the same blocks where census enumerators roamed in early April 1940. “Stand firm on your Constitutional Rights” it warned. The Constitutional Rights Republican League of Minnesota jeered “Washington Bureaucrats” and their “snooping.” They called on individuals to refuse to cooperate. Few appear to have taken the call to heart. This was a point that census officials celebrated. But as I came to realize while investigating the census returns for small-town Minnesota, the so-called Washington Bureaucrats achieved this success after they preemptively limited their own “snooping.” Many Minnesotans (and their fellow ordinary Americans) may have seen no need to refuse because they could comply with census takers and still keep their household finances secret. -

The Imaginary Partners of Alaska

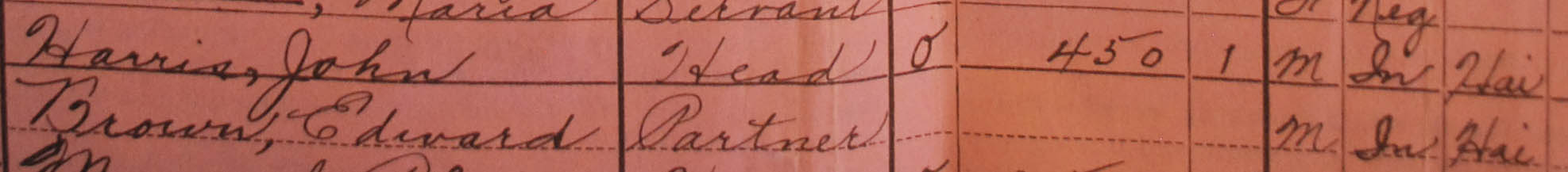

Since my last post, I’ve discovered more about how Census Bureau officials trained census takers to label adults living together as “partners.” They wrote census stories.

Since my last post, I’ve discovered more about how Census Bureau officials trained census takers to label adults living together as “partners.” They wrote census stories. -

The Partners of Greenwich Village

It’s been over 15 years since I married. For most of those years, I spoke of being a husband, of having a wife. That changed when the person who I married—and to whom I remain married—began what we did not then realize was a process that would end with him coming out as transgender. Gendered pronouns were to change, but first we wrestled with the language of relationship. We tried on “spouse” for a while—as in, “my spouse taught our son to climb trees,” (which is true). I felt awkward in the usage at first—it isn’t common—but eventually got used to it and even liked it. My spouse never did. We tossed around “partner,” but wasn’t that too businesslike? (Or maybe too queer for how we then made sense, or tried to, of ourselves.) But since spouse did not catch on, and “lover” only worked for a laugh, we landed on “partner” after all. I thought we were being very modern, that this was a new sort of relationship. Then a census-related query from historian Ansley Erickson proved me very wrong.

-

I'm gonna put down K-A-Y

How does one maintain one’s dignity even when in the clutches of a pre-printed bureaucratic schedule? How does one assert oneself in a world of officials who insist on knowing one—and one’s business? These are questions driving the census poetry of Langston Hughes.

-

Paths to 87 Hamilton Place

At 87 Hamilton Place in New York’s Harlem neighborhood, just blocks away from City College, Lucile Kenn encountered and enumerated glimpses into a transnational nation, a nation of nations. In one apartment she sketched out the statistical life of the Hungarian-born artist Lily Furedi, whose portraits of American life I’ve already discussed. Furedi represented a by-then-fading mode of migration, a person or family moving from the “Old World” to the “New.” Immigration restriction laws passed in 1924 had been designed precisely to keep out people like Furedi and the few Bulgarians and Russians in the building. Three doors down from the Furedis, Kenn interviewed a family who migrated by a different route, who had followed paths worn clear by the ships of American empire: Mercedes Hizcarondo married to Manuel, both from Puerto Rico, and their son, another Manuel, born a New Yorker.

-

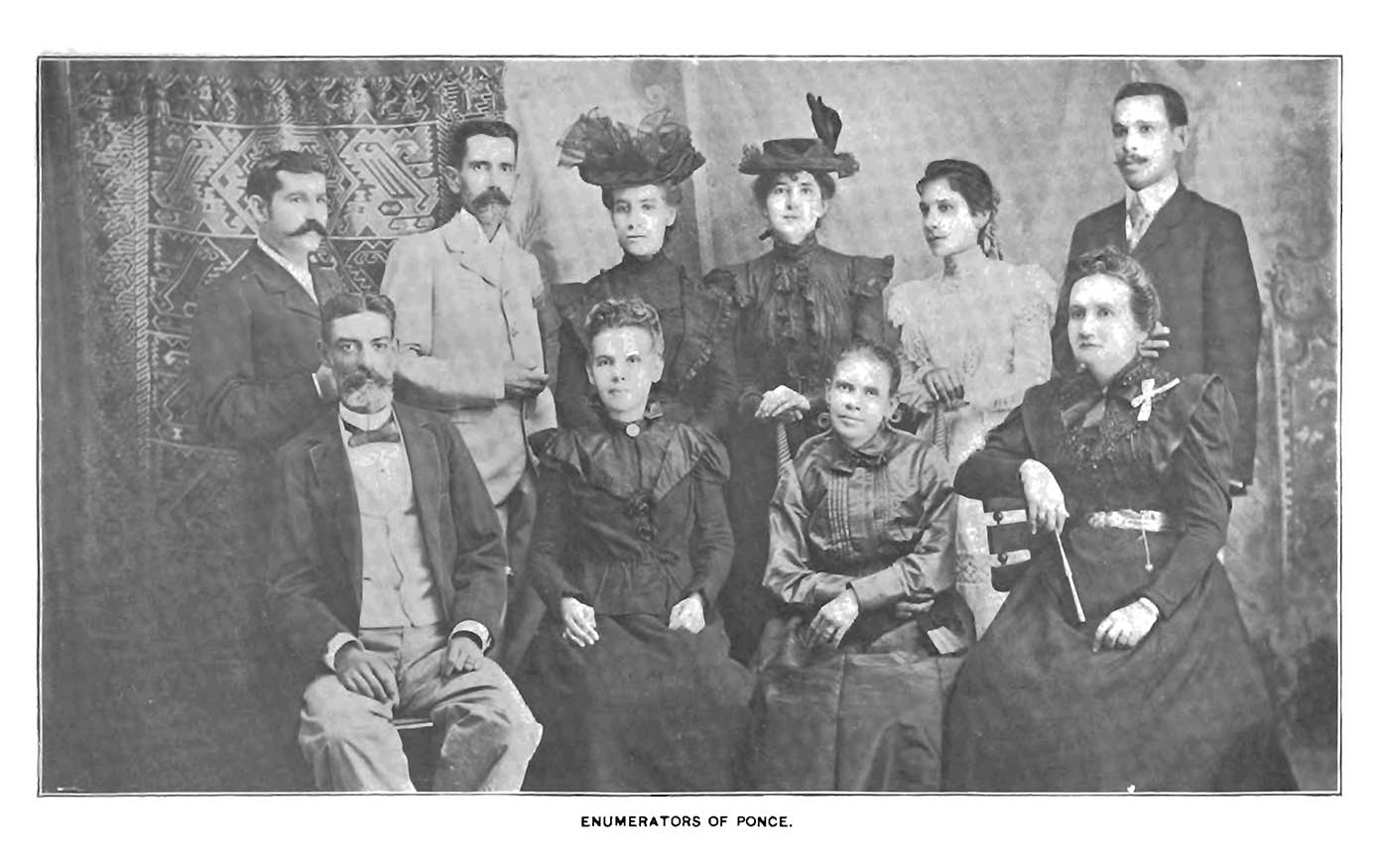

When the U.S. Counted Puerto Ricans for the First Time

-

The Muralist and Enumerator

The records of the U.S. Census Bureau reside in Washington, D.C., in the National Archives building built in the depths of the Great Depression to provide a monumental home to federal records. Inside those acres of white marble visitors encountered the founding of the United States in murals and on parchment. Instead of “Washington Crossing the Delaware,” a martial celebration of the nation’s birth through grit and force, the exhibition hall presented a nation made on paper. While tourists today still line up on the Constitution Avenue steps to pay respects to the Bill of Rights or Declaration of Independence, genealogists and other researchers like me breeze through the Pennsylvania Ave entrance and (after some card swiping and paper shuffling) take our seats at grand wooden desks in a well-lit, stately reading room. Researchers call the facility, affectionately, NARA-1, distinguishing it from the much larger, but less grand -National Archives facility in College Park, MD.

-

One Nation, Mature and Manageable

The census of 1940 proved to Stuart Chase that the U.S. population could now be accurately predicted. Of course, he was wrong^, but he did not know that. More importantly, the (wrong) predictions he now believed pointed toward a conclusion he was glad to embrace. America was on the path to maturity, and as a mature nation it not only could be better managed by a new technocratic elite, but indeed would need to be managed.

-

A Predictable Population

What does each census mean? What story does it tell? For Stuart Chase, the census of 1940 proved that America had become, if not boring, then at least predictable.

-

'The Community of Work Goes Beyond the State it Serves'

In my last post, I drew on Jesse Ball’s lovely, world-expanding novel Census to recast the census, which too often summons to mind dry facts on yellowed paper, as something more like a quest, one mobilizing hundreds of thousands of ordinary individuals to record the lives of millions and millions more. Ball’s novel confirms my own hunch that each census brims with narrative potential.

-

'Into a tempest with a lantern'

Earlier this year, Jesse Ball published a novel titled Census, commanding prominent bookstore placements and proportionate acclaim: Ball’s “best to date” according to the NY Times, an “unusual, impressive novel” says The Guardian, by a “singular author” say the LA Times, and from the Washington Post we get “strange and exploratory,” which really is both apt and fittingly high praise. I loved this book for how odd it was, for how beautiful it was, and for much beauty it found in all that can be written off as odd.

-

Why A Census Matters

Why does the census matter? A few answers appear often in recent reporting and opinion pieces worrying that the Trump administration may be sabotaging the 2020 census, by underfunding, inadequate staffing, and questions about citizenship that could deter participation. A lot is at stake, such writing correctly reveals: the distribution of $600 billion in federal funds depends on census counts, as does the allocation of representatives among the States. (Recall: the Constitution created the census count in order to fairly apportion representatives and levy direct taxes). Business too depends on census figures, especially the ‘research industry’ which makes money by gathering, repackaging, analyzing, and selling free government data. We need not be surprised that political writers emphasize the (immense) political significance of the census. To them, the census is about wealth and power.

-

'All My Secrets for Uncle Sam'

Madge C. Crandall did not want to talk about her radio. Among other things. But Mollie Levi’s job was to ask her about it. And many other things.

subscribe via RSS